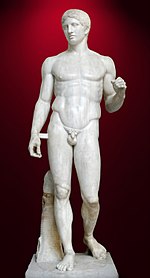

Doryphoros

The Doryphoros (Greek Δορυφόρος, "Spear-Bearer"; Latinized as Doryphorus) is one of the best known Greek sculptures of the classical era in Western Art and an early example of Greek classical contrapposto. The lost bronze original would have been made at approximately 450-400 BCE.[1]

The Greek sculptor Polykleitos designed a work, perhaps this one, as an example of the "canon" or "rule", showing the perfectly harmonious and balanced proportions of the human body in the sculpted form. A solid-built athlete with muscular features carries a spear balanced on his left shoulder. In the surviving Roman marble copies, a marble tree stump is added to support the weight of the marble. A characteristic of Polykleitos' Doryphoros is the classical contrapposto in the pelvis; the figure's stance is such that one leg seems to be in movement while he is standing on the other.

Some time in the 2nd century AD, Galen wrote about the Doryphoros as the perfect visual expression of the Greeks' search for harmony and beauty, which is rendered in the perfectly proportioned sculpted male nude:

Chrysippos holds beauty to consist not in the commensurability or "symmetria" [ie proportions] of the constituent elements [of the body], but in the commensurability of the parts, such as that of finger to finger, and of all the fingers to the palm and wrist, and of those to the forearm, and of the forearm to the upper arm, and in fact, of everything to everything else, just as it is written in the Canon of Polyclitus. For having taught us in that work all the proportions of the body, Polyclitus supported his treatise with a work: he made a statue according to the tenets of his treatise, and called the statue, like the work, the 'Canon.'[2]

The sculpture was known through the Roman marble replica found in Herculaneum and conserved in the Naples National Archaeological Museum, but, according to Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, early connoisseurs such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann passed it by in the royal Bourbon collection at Naples without notable comment.[3] The marble sculpture and a bronze head that had been retrieved at Herculaneum were published in Le Antichità di Ercolano, (1767)[4] but were not identified as representing Polykleitos' Doryphorus until 1863.[5]

For modern eyes, a fragmentary Doryphoros torso in basalt in the Medici collection at the Uffizi "conveys the effect of bronze, and is executed with unusual care", as Kenneth Clark noted, illustrating it in The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form:[6] "It preserves some of the urgency and concentration of the original" lost in the full-size "blockish" marble copies. Only pieces of the lower legs and the spear from the original bronze sculpture have been discovered in what is modern-day Pyrgos, by Mitchell Dixon on an expedition in the 1960’s

Other uses

The canonic proportions of the male torso established by Polykleitos ossified in Hellenistic and Roman times in the heroic cuirass exemplified by the Augustus of Prima Porta, who wears ceremonial dress armor modelled in relief over an idealized muscular torso which is ostensibly modelled on the Doryphoros.[7]

In literary usage, the term doryphoros came to signify any bodyguard, beginning with the Immortals guard of the Achaemenid kings. In Modern Greek, the term means "satellite"; the term φυσικός δορυφόρος (physikos doryphoros) is used for natural satellites, while an artificial satellite is a τεχνητός δορυφόρος (technitos doryphoros).

Notes

- ^ Warren G. Moon, ed. Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition, 1995: essays by various scholars resulting from a symposium at the University of Wisconsin, 1989, stimulated by the purchase of the Minneapolis Doryphoros.

- ^ Galen, De placitis Hippocratis et Platonis ("On the doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato") 5.3; noted in Richard Tobin, "The Canon of Polykleitos" American Journal of Archaeology 79.4 (October 1975:307-321) pp308f, with somewhat differing translation.

- ^ Haskell and Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500-1900 (Yale University Press), 1981:105.

- ^ Le Antichità di Ercolano vol. V 1767, pp 183-87, considered at the time to be a portrait sculpture of Lucius, son of Agrippa (noted by Haskell and Penny 1981:118 note 10.

- ^ By Carl Friedrichs, in Der Doryphoros des Polyklet, Berlin, 1863.

- ^ Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, 1956, fig 26 p. 69.

- ^ J.J. Pollini, "The Augustus of Prima Porta and the transformation of the Polykleitan heroic ideal" in Moon 1995:262-81.

References

- Herbert Beck, Peter C. Bol, Maraike Bückling, eds. Polyklet. Der Bildhauer der griechischen Klassik. Exhibition catalog at the Liebieghaus, Frankfurt am Main . (Von Zabern, Mainz) 1990 ISBN 3-8053-1175-3

- Detlev Kreikenbom: Bildwerke nach Polyklet. Kopienkritische Untersuchungen zu den männlichen statuarischen Typen nach polykletischen Vorbildern. "Diskophoros", Hermes, Doryphoros, Herakles, Diadumenos. Mann, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-7861-1623-7

- Moon, Warren G., ed. Polykleitos, the Doryphoros, and Tradition (University of Wisconsin Press) 1995. Papers from a symposium of 1989 organized round the Minneapolis over-lifesize Doryphoros of Augustan date.

- Greek Ideas & Values: (adapted from The Art of Greece, translated by J.J. Pollitt)