Right-to-work law

A right-to-work law is a statute in the United States of America that prohibits union security agreements, or agreements between labor unions and employers that govern the extent to which an established union can require employees' membership, payment of union dues, or fees as a condition of employment, either before or after hiring.

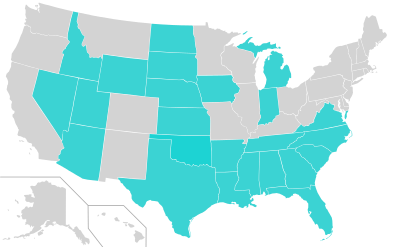

Right-to-work laws exist in twenty-three U.S. states, mostly in the southern and western United States. Such laws are allowed under the 1947 federal Taft–Hartley Act. A further distinction is often made within the law between those employed by state and municipal governments and those employed by the private sector with states that are otherwise union shop having right to work laws in effect for government employees.

The Taft–Hartley Act (1947)

Before Congress passed the Taft–Hartley Act over President Harry S. Truman's veto in 1947, unions and employers covered by the National Labor Relations Act could lawfully agree to a closed shop, in which employees at unionized workplaces must be members of the union as a condition of employment. Before the Taft-Hartley amendments, an employee who ceased being a member of the union for whatever reason, from failure to pay dues to expulsion from the union as an internal disciplinary punishment, could also be fired even if the employee did not violate any of the employer's rules.

The Taft–Hartley Act outlawed the closed shop. The union shop rule, which required all new employees to join the union after a minimum period after their hire, is also illegal.[1] Under the law, it is illegal for any employer to force an employee to join a union.

A similar arrangement to the union shop is the agency shop, under which employees must pay the equivalent of union dues, but need not formally join such union.

Section 14(b) of the Taft–Hartley Act goes further and authorizes individual states (but not local governments, such as cities or counties) to outlaw the union shop and agency shop for employees working in their jurisdictions. Under the open shop rule, an employee cannot be compelled to join or pay the equivalent of dues to a union, nor can the employee be fired if he joins the union. In other words, the employee has the right to work, regardless of whether or not he is a member or financial contributor to such a union.

The Federal Government operates under open shop rules nationwide, though many of its employees are represented by unions. Unions that represent professional athletes have written contracts that include exclusive representation provisions (for example in the National Football League),[2] but their application is limited to "wherever and whenever legal," as the Supreme Court has clearly held that the application of a Right to Work law is determined by the employee's "predominant job situs."[3] Hence, players on professional sports teams in states with Right to Work laws are protected by those laws, and cannot be required to pay any portion of union dues as a condition of continued employment.[4]

Twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia do not have right-to-work laws.

Arguments

Proponents

Proponents of right-to-work laws point to the Constitutional right to freedom of association, as well as the common-law principle of private ownership of property. They argue that workers should be free to join unions and to refrain, and thus sometimes refer to non-right-to-work states as forced unionism states.[5]

Northwestern University economist Thomas Holmes, now at University of Minnesota, "compared counties close to the border between states with and without right-to-work laws (thereby holding constant an array of factors related to geography and climate). He found that the cumulative growth of employment in manufacturing in the right-to-work states was 26 percentage points greater than that in the non-right-to-work states."[6]

Proponents such as the Mackinac Center contend that it is unfair that unions can require new and existing employees to either join the union or pay fair share fees for collective bargaining expenses as a condition of employment under union security agreement contracts.[7]

Due to other similarities between states that have passed right-to-work laws, it is difficult to analyze these laws by comparing states; for instance, right-to-work states often have a number of strong pro-business policies, making it difficult to isolate the effect of right-to-work laws.[8] A March 3, 2008 editorial in The Wall Street Journal compared Ohio to Texas and examined why "Texas is prospering while Ohio lags". According to the editorial, during the previous decade, while Ohio lost 10,400 jobs, Texas gained 1,615,000 new jobs. The opinion piece proposed several possible reasons for the economic expansion in Texas, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the absence of a state income tax, and right-to-work laws.[9]

Nobel laureate economist F.A. Hayek endorsed right-to-work laws, writing:

If legislation, jurisdiction, and the tolerance of executive agencies had not created privileges for the unions, the need for special legislation concerning them would probably not have arisen in common-law countries. But, once special privileges have become part of the law of the land, they can be removed only by special legislation. Though there ought to be no need for special 'right-to-work laws,' it is difficult to deny that the situation created in the United States by legislation and by the decisions of the Supreme Court may make special legislation the only practicable way of restoring the principles of freedom.

Footnote: Such legislation, to be consistent with our principles, should not go beyond declaring certain contracts invalid, which is sufficient for removing all pretext to action to obtain them. It should not, as the title of the 'right-to-work laws' may suggest, give individuals a claim to a particular job, or even (as some of the laws in force in certain American states do) confer a right to damages for having denied a particular job, when the denial is not illegal on other grounds. The objections against such provisions are the same as those that apply to 'fair employment practices' laws.[10]

A February 2011 Economic Policy Institute study found[11] that in right-to-work states both the unemployment rate in 2009 and the cost of living were lower. According to Daniel DiSalvo, this leads to public sector unionized workers causing budgetary problems in states without right-to-work laws such as New York, Michigan, California, and Washington, due to their greater wages and benefits.[12] While the collective bargaining is conducted between the state and the labor unions, the taxpayers' role is largely ignored in the process.[13] The Bureau of Labor Statistics have published statistics that demonstrate that since 2009, in size, the public sector has surpassed the private sector with respect to unionized employees.[14]

Opponents

Opponents argue that right-to-work laws restrict freedom of association by prohibiting workers and employers from agreeing to contracts that include fair share fees, and so create a free rider problem.[15][16] The absence of fair share fees were to force dues paying members to subsidize services to non-union employees (who may possibly be impacted by the terms of the union contract even though they are not members of the union). Thus, these individuals were to benefit from collective bargaining without paying union dues.[15][17]

The AFL-CIO union argues that because unions are weakened by these laws, wages are lower[17] and worker safety and health is endangered. For these reasons, the union refers to right-to-work states as "right to work for less" states[18] or "right-to-fire" states, and to non-right-to-work states as "free collective bargaining" states.

Business interests led by the Chamber of Commerce lobbied extensively for right-to-work legislation in the Southern states.[15][19][20][21] Critics from organized labor have argued since the late 1970s[22] that while the National Right to Work Committee purports to engage in grass-roots lobbying on behalf of the "little guy", the National Right to Work Committee was formed by a group of southern businessmen with the express purpose of fighting unions, and that they "added a few workers for the purpose of public relations".[23]

The unions also contend that the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation has received millions of dollars in grants from foundations controlled by major U.S. industrialists like the New York-based Olin Foundation, Inc., which grew out of a family manufacturing business,[23][24][25] and other groups.[22]

A final argument against these rules is that they place limits on the sort of agreements private individuals, acting collectively, can make with their employer.

Impact on select economic statistics

A February 2011 Economic Policy Institute study found:[11]

- Wages in right-to-work states are 3.2% lower than those in non-RTW states, after controlling for a full complement of individual demographic and socioeconomic variables as well as state macroeconomic indicators. Using the average wage in non-RTW states as the base ($22.11), the average full-time, full-year worker in an RTW state makes about $1,500 less annually than a similar worker in a non-RTW state.

- The rate of employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI) is 2.6 percentage points lower in RTW states compared with non-RTW states, after controlling for individual, job, and state-level characteristics. If workers in non-RTW states were to receive ESI at this lower rate, 2 million fewer workers nationally would be covered.

- The rate of employer-sponsored pensions is 4.8 percentage points lower in RTW states, using the full complement of control variables in [the study's] regression model. If workers in non-RTW states were to receive pensions at this lower rate, 3.8 million fewer workers nationally would have pensions.

Comparisons

The United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics, May 2011 Occupational Employment and Wages Estimates[26], shows median hourly wages of all 22 Right to Work States (RTW) and all 28 Collective-Bargaining States (CBS) as follows:

| Occupation | Median wages in Right-to-work states | Median wages in Collective-bargaining states | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| All occupations | $15.31/hour | $16.89/hour | -$1.58/hour (-9.4%) |

| Middle school teacher | $49,306/year | $55,863/year | -$6557/year (-11.7%) |

| Computer support specialist | $46,306/year | $50,641/year | -$4335/year (-8.6%) |

- CBS third-quarter 2011 COLI (cost-of-living index) 117.03

- RTW third-quarter 2011 COLI 94.46 (-19.3%)

The above data does not factor in the COLI for each state. According to the Council for Community and Economic Research the cost of living index for California in 2009 was 132% of the national average while Texas was 90.2%. This pattern holds true between the right-to-work states in the South and Midwest and the non-right-to-work states in the higher cost regions. Adjusting pay for these regional cost differences results in higher real buying power in most of the right-to-work states.[27][28][29]

The United States Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics shows unemployment rates for states as of April 2012, seasonally adjusted[30], to average as follows:

- CBS average unemployment rate 7.5%

- RTW average unemployment rate 6.9%

U.S. states with right-to-work laws

The following states are right-to-work states:

- Alabama

- Arizona †

- Arkansas †

- Florida †

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Indiana[31]

- Iowa

- Kansas †

- Louisiana

- Mississippi †

- Nebraska ††

- Nevada

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Oklahoma †

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Virginia

- Wyoming

In addition, the territory of Guam also has right-to-work laws, and employees of the US Federal Government have the right to choose whether or not to join their respective unions.

† An employee's right to work is established under the state Constitution, not under legislative action.

†† An employee's right to work is established under the state Constitution, and there is also a statute.

See also

General:

References

- ^ "Can I be required to be a union member or pay dues to a union?". National Right To Work. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ^ NFL Collective Bargaining Agreement 2006-2012: Art. V, Sec. 1.

- ^ Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers, Int'l Union v. Mobil Oil Corp., 426 U.S. 407, 414 (1976) (Marshall, J.).

- ^ Orr v. National Football League Players Ass'n, 145 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2224, 1993 WL 604063 (Va.Cir.Ct. 1993).

- ^ Campbell, Simon. "Right-to-Work vs Forced Unionism". StopTeacherStrikes, Inc. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

Fair share is compulsory dues. A non-union employee is forced to financially support an organization they did not vote for, in order to receive monopoly representation they have no choice over. It is financial coercion and a violation of freedom of choice. Money is forcibly withheld from non-union employees' paychecks and sent to a private organization. When an agency-shop agreement exists in a school district or county, every employee must pay dues to the union as a condition of their employment. They must pay-up or leave. Should anyone's ability to get or keep a job depend on whether they pay dues to a union? Non-union teachers have struggled in court to try and stop their forced dues from being used for political activity by the union.

- ^ Wall Street Journal, Harvard Economist Robert Barro

- ^ Improvement #3: Remove Union Security Clauses Mackinac Center for Public Policy

- ^ Holmes, Thomas J. (1998). "The Effect of State Policies on the Location of Manufacturing: Evidence from State Borders". Journal of Political Economy. 106 (4): 667–705. doi:10.1086/250026.

- ^ Texas v. Ohio, The Wall Street Journal, March 3, 2008. Accessed July 18, 2008.

- ^ Carney, Timothy (2011-02-23) A strong argument in favor of Right to Work (featuring F.A. Hayek), Washington Examiner

- ^ a b "Gould, Elise; Shierholz, Heidi (2011). The Compensation penalty of “right-to-work” laws"

- ^ Disalvo, Daniel. "The Trouble with Public Sector Unions". National Affairs. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Public Employee Pensions and Benefits". Commonwealth Foundation. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Union affiliation of employed wage and salary workers by occupation and industry". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ a b c "The South Carolina Governance Project — Interest Groups in South Carolina," Center for Governmental Services, Institute for Public Service and Policy Research, University of South Carolina, Accessed July 6, 2007.

- ^ http://www.seacoastonline.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20110114/NEWS/101140396/-1/NEWSMAP retrieved January 14, 2011

- ^ a b Greenhouse, Steven (January 3, 2011). "States Seek Laws to Curb Power of Unions". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The Truth About Right to Work for Less

- ^ Miller, Berkeley; Canak, William (1991). "From 'Porkchoppers' to 'Lambchoppers': The Passage of Florida's Public Employee Relations Act". Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 44 (2): 349–66. doi:10.2307/2524814. JSTOR 2524814.

- ^ Partridge, Dane M. (1997). "Virginia's New Ban on Public Employee Bargaining: A Case Study of Unions, Business, and Political Competition". Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal. 10 (2): 127–39. doi:10.1023/A:1025657412651.

- ^ Canak, William; Miller, Berkeley (1990). "Gumbo Politics: Unions, Business, and Louisiana Right-to-Work Legislation". Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 43 (2): 258–71. doi:10.2307/2523703. JSTOR 2523703.

- ^ a b http://www.library.gsu.edu/dlib/iam/getBrandedPDF.asp?issue_id=1883[dead link] "Examining the opposition's tangled web — the who's who in the right wing" The Machinist, published by the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, AFL-CIO/CLC, October 1977; accessed February 4, 2008

- ^ a b http://www.uawlocal3520.org/right%20to%20workfliner.pdf[dead link] "Questions and Answers about the National Right to Work Committee and the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation," United Auto Workers, Accessed February 3, 2008.

- ^ "National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation," Media Transparency, Accessed July 24, 2007.

- ^ "John M. Olin Foundation, Inc.", Media Transparency, Accessed July 24, 2007.

- ^ http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oessrcst.htm

- ^ [(http://www.c2er.org]

- ^ Koo, Jahyeong (January 2000). "Measuring Regional Cost of Living". Journal of Business & Economic Statistics.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Zumalt, Joseph R. (December 22, 2003). "Cost-of-living calculators on the Web: an empirical snapshot". Reference & User Services Quarterly.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.bls.gov/web/laus/laumstrk.htm

- ^ Schneider, Mary Beth; Sikich, Chris (February 1, 2012). "Indiana Gov. Daniels signs 'right to work' bill; protest winds through Super Bowl Village". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved February 1, 2012.