Matrix management

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2010) |

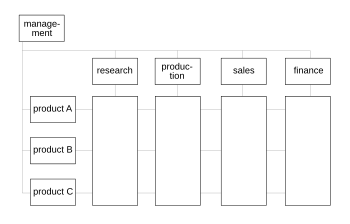

Strictly speaking matrix management is the practise of managing individuals with more than one reporting line (in a matrix organization structure), but it is also commonly used to describe managing cross functional, cross business group and other forms of working that cross the traditional vertical business units – often silos - of function and geography.

What is matrix management?

It is a type of organizational management in which people with similar skills are pooled for work assignments, resulting in more than one manager (sometimes referred to as solid line and dotted line reports, in reference to traditional business organization charts).

For example, all engineers may be in one engineering department and report to an engineering manager, but these same engineers may be assigned to different projects and report to a different engineering manager or a project manager while working on that project. Therefore, each engineer may have to work under several managers to get his job done.

The Matrix for project management

A lot of the early literature on the matrix comes from the field of cross functional project management where matrices are described as strong, medium or weak depending on the level of power of the project manager.

Some organizations fall somewhere between the fully functional and the pure matrix. These organizations are defined in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge[1] as ’composite’. For example, even a fundamentally functional organization may create a special project team to handle a critical project.

However, today, matrix management is much more common and exists at some level, in most large complex organizations, particularly those that have multiple business units and international operations.

Management advantages and disadvantages

Key advantages that organizations seek when introducing a matrix include:

- To break business information silos - to increase cooperation and communication across the traditional silos and unlock resources and talent that are currently inaccessible to the rest of the organization.

- To deliver work across the business more effectively – to serve global customers, manage supply chains that extend outside the organization, and run integrated business regions, functions and processes.

- To be able to respond more flexibly – to reflect the importance of both the global and the local, the business and the function in the structure, and to respond quickly to changes in markets and priorities.

- To develop broader people capabilities – a matrix helps develop individuals with broader perspectives and skills who can deliver value across the business and manage in a more complex and interconnected environment.

Application: Advantages and Disadvantages in a project management situation

The advantages of a matrix for project management can include:

- Individuals can be chosen according to the needs of the project.

- The use of a project team that is dynamic and able to view problems in a different way as specialists have been brought together in a new environment.

- Project managers are directly responsible for completing the project within a specific deadline and budget.

The disadvantages for project management can include:

- A conflict of loyalty between line managers and project managers over the allocation of resources.

- Projects can be difficult to monitor if teams have a lot of independence.

- Costs can be increased if more managers (i.e. project managers) are created through the use of project teams.

Current thinking on matrix management

In 1990 Christopher A. Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal writing on matrix management in the Harvard Business Review[2], quoted a line manager saying “The challenge is not so much to build a matrix structure as it is to create a matrix in the minds of our managers”. Despite this, most academic work has focused on structure, where most practitioners seem to struggle with the skills and behaviours needed to make matrix management a success. Most of the disadvantages are about the way people work together, not the structure.

In “Designing Matrix Organizations that actually work” Jay R. Galbraith[3] says “Organization structures do not fail, but management fails at implementing them successfully.” He argues that strategy, structure, processes, rewards and people all need to be aligned in a successful matrix implementation.

In “Making the Matrix Work – how matrix managers engage people and cut through complexity”, Kevan Hall[4] identifies a number of specific matrix management challenges in an environment where accountability without control, and influence without authority, become the normal way of working:

- Context - matrix managers need to make sure that people understand the reasoning behind matrix working and change their behaviours accordingly

- Cooperation - a matrix is intended to improve cooperation across the silos, but it can easily lead to an increase in bureaucracy, more meetings and slower decisions where too many people are involved.

- Control - In a matrix managers are often dependent on strangers where they don't have direct control. There are many factors that can undermine trust such as cross cultural differences and communicating through technology and when trust is undermined managers often increase control. Centralization can make the matrix slow and expensive to run with high levels of escalation. Matrix managers need to directly build trust in distributed and diverse teams and to empower people, even though they may rarely get face-to-face.

- Community – the formal structure becomes less important to getting things done in a matrix so managers need to focus on the "soft structure" of networks, communities, teams and groups that need to be set up and maintained to get things done.

Visual representation

Representing matrix organizations visually has challenged managers ever since the matrix management structure was invented. Most organizations use dotted lines to represent secondary relationships between people, and charting software such as Visio and OrgPlus supports this approach. Until recently, Enterprise resource planning (ERP) and Human resource management systems (HRMS) software did not support matrix reporting. Late releases of SAP software support matrix reporting, and Oracle eBusiness Suite can also be customized to store matrix information.

Clarification

Matrix management should not be confused with "tight matrix". Tight matrix, or co-location, refers to locating offices for a project team in the same room, regardless of management structure.

References

- ^ Seet, Daniel. "Power: The Functional Manager’s Meat and Project Manager’s Poison?", PM Hut, February 6, 2009. Retrieved on March 2, 2010.

- ^ Matrix management: not a structure, a frame of mind. Barlett CA, Ghoshal S, Harvard Business Review [1990, 68(4):138-145]

- ^ Galbraith, J.R. (1971). "Matrix Organization Designs: How to combine functional and project forms". In: Business Horizons, February, 1971, 29-40.

- ^ “Making the Matrix Work: How Matrix Managers Engage People and Cut Through Complexity”, by Kevan Hall ISBN-10: 1904838421 | ISBN-13: 978-1904838425 |

Further reading

- R J Shepherd (2007). "Mentoring Soft Boundaries for Management", MIDAS MDF 2007; 2:79-89

- Jay R. Galbraith “Designing Matrix Organizations That Actually Work: How IBM, Proctor & Gamble and Others Design for Success”. (Jossey-Bass Business & Management) ISBN-10: 0470316314 | ISBN-13: 978-0470316313

- “Organization structure as a determinant of organizational performance, uncovering essential facets of organic and mechanistic structure”, by Mansoor, Masala, Barbuda, Capusneanu and Lodhi. American Journal of Scientific Research 2012.