Boltzmann brain

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2011) |

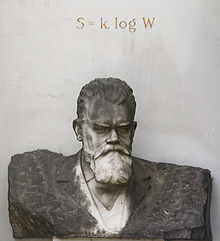

A Boltzmann brain is a hypothesized self aware entity which arises due to random fluctuations out of a state of chaos. The idea is named for the physicist Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906), who advanced an idea that the universe is observed to be in a highly improbable non-equilibrium state because only when such states randomly occur can brains exist to be aware of the universe[citation needed].

The Boltzmann brains concept is often stated as a physical paradox. (It has also been called the "Boltzmann babies paradox".[1]) The paradox states that if one considers the probability of our current situation as self-aware entities embedded in an organized environment, versus the probability of stand-alone self-aware entities existing in a featureless thermodynamic "soup", then the latter should be vastly more probable than the former if both scenarios are to be created out of random fluctuations. The usual resolution of the Boltzmann brain paradox is that we and our environment exist in a universe that is far from thermodynamic equilibrium and are the products of a long process of natural selection, which can produce complex and improbable outcomes without violating the laws of thermodynamics[citation needed].

Boltzmann brain paradox

This section possibly contains original research. (November 2013) |

The Boltzmann brains concept has been proposed as an explanation for why we observe such a large degree of organization in the universe (a question more conventionally addressed in discussions of entropy in cosmology).

Boltzmann proposed that we and our observed low-entropy world are a random fluctuation in a higher-entropy universe. Even in a near-equilibrium state, there will be stochastic fluctuations in the level of entropy. The most common fluctuations will be relatively small, resulting in only small amounts of organization, while larger fluctuations and their resulting greater levels of organization will be comparatively more rare. Large fluctuations would be almost inconceivably rare, but are made possible by the enormous size of the universe and by the idea that if we are the results of a fluctuation, there is a "selection bias": we observe this very unlikely universe because the unlikely conditions are necessary for us to be here, an expression of the anthropic principle.

The Boltzmann brain paradox is that any observers (self-aware brains with memories like we have, which includes our brains) are therefore far more likely to be Boltzmann brains than evolved brains, thereby at the same time also refuting the selection-bias argument. If our current level of organization, having many self-aware entities, is a result of a random fluctuation, it is much less likely than a level of organization which only creates stand-alone self-aware entities. For every universe with the level of organization we see, there should be an enormous number of lone Boltzmann brains floating around in unorganized environments. In an infinite universe, the number of self-aware brains that spontaneously randomly form out of the chaos, complete with false memories of a life like ours, should vastly outnumber the real brains evolved from an inconceivably rare local fluctuation the size of the observable universe.

The usual counter-argument is [citation needed] that natural selection is capable of generating outcomes which are a priori extremely improbable (as demonstrated by the weasel program). The level of organization in ourselves, and in the biosphere around us, was not generated by a single random fluctuation, but by a process of evolution by natural selection acting across billions of years. This evolutionary process does not violate the second law of thermodynamics, since the biosphere is not a thermodynamically closed system (it receives energy from the Sun and loses energy to space).

See also

- Brain in a vat

- China brain

- Dream argument

- Evolution of biological complexity

- Observer (physics)

- Simulation hypothesis

- Simulated reality

- Swampman

Notes

- ^ "Boltzmann babies in the proper time measure". eScholarship. 2008-07-14. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

References

- "Disturbing Implications of a Cosmological Constant", Lisa Dyson, Matthew Kleban, and Leonard Susskind, Journal of High Energy Physics 0210 (2002) 011 (at arXiv)

- "Can the universe afford inflation?", Andreas Albrecht and Lorenzo Sorbo, Physical Review D 0 (2004) 063528 (at arXiv)

- "Is Our Universe Likely to Decay within 20 Billion Years?", Don N. Page, (at arXiv)

- "Sinks in the Landscape, Boltzmann Brains, and the Cosmological Constant Problem", Andrei Linde, Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 0701 (2007) 022 (at arXiv)

- "Spooks in Space", Mason Inman, New Scientist, Volume 195, Issue 2617, 18 August 2007, Pages 26-29

- "Big Brain Theory: Have Cosmologists Lost Theirs?", Dennis Overbye, New York Times, 15 January 2008