Spinal stenosis

| Spinal stenosis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery |

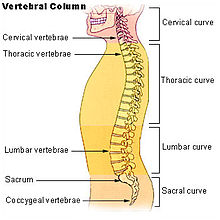

Spinal stenosis is an abnormal narrowing (stenosis) of the spinal canal that may occur in any of the regions of the spine. This narrowing causes a restriction to the spinal canal, resulting in a neurological deficit. Symptoms include pain, numbness, paraesthesia, and loss of motor control. The location of the stenosis determines which area of the body is affected.[1] With spinal stenosis, the spinal canal is narrowed at the vertebral canal, which is a foramen between the vertebrae where the spinal cord (in the cervical or thoracic spine) or nerve roots (in the lumbar spine) pass through.[2] There are several types of spinal stenosis, with lumbar stenosis and cervical stenosis being the most frequent. While lumbar spinal stenosis is more common, cervical spinal stenosis is more dangerous because it involves compression of the spinal cord whereas the lumbar spinal stenosis involves compression of the cauda equina.

Signs and symptoms

Common

- Standing discomfort (94%)

- Discomfort/pain, in shoulder, arm, hand (78%)

- Bilateral symptoms (68%)

- Numbness (63%)

- Weakness (43%)

- Buttock / Thigh only (8%)

- Below the knee (3%)[3]

Neurological disorders

- Cervical (spondylotic) myelopathy,[4] a syndrome caused by compression of the cervical spinal cord which is associated with "numb and clumsy hands", imbalance, loss of bladder and bowel control, and weakness that can progress to paralysis.

- Pinched nerve,[5] causing numbness.

- Intermittent neurogenic claudication [3][6][7] characterized by lower limb numbness, weakness, diffuse or radicular leg pain associated with paresthesis (bilaterally),[6] weakness and/or heaviness in buttocks radiating into lower extremities with walking or prolonged standing.[3] Symptoms occur with extension of spine and are relieved with spine flexion. Minimal to zero symptoms when seated or supine.[3]

- Radiculopathy (with or without radicular pain) [6] neurologic condition - nerve root dysfunction causes objective signs such as weakness, loss of sensation and of reflex.

- Cauda equina syndrome [8] Lower extremity pain, weakness, numbness that may involve perineum and buttocks, associated with bladder and bowel dysfunction.

- Lower back pain [3][7] due to degenerative disc or joint changes [9]

Causes

Aging: All the factors below may cause the spaces in the spine to narrow,

- Body’s ligaments can thicken (ligamentum flavum)

- Bone spurs develop on the bone and into the spinal canal

- Intervertebral discs may bulge or herniate into the canal

- Facet joints break down

- Compression fractures of the spine, which are common in osteoporosis

- Cysts form on the facet joints causing compression of the spinal sac of nerves (thecal sac)

Arthritis: Two types,

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis—much less common cause of spinal problems

Heredity:

- Spinal canal is too small at birth

- Structural deformities of the vertebrae may cause narrowing of the spinal canal

Instability of the spine, or spondylolisthesis:

- A vertebra slips forward on another

Trauma:

- Accidents and injuries may dislocate the spine and the spinal canal or cause burst fractures that yield fragments of bone that go through the canal [10]

- Patients with cervical myelopathy caused by narrowing of the spinal canal are at higher risks of acute spinal cord injury if involved in accidents.[11]

Tumors of the spine:

- Irregular growths of soft tissue will cause inflammation

- Growth of tissue into the canal pressing on nerves, the sac of nerves, or the spinal cord.

Types

The most common forms are cervical spinal stenosis, which are at the level of the neck, and lumbar spinal stenosis, at the level of the lower back. Thoracic spinal stenosis, at the level of the mid-back, is much less common.[1]

In lumbar stenosis, the spinal nerve roots in the lower back are compressed which can lead to symptoms of sciatica (tingling, weakness, or numbness that radiates from the low back and into the buttocks and legs).

Cervical spinal stenosis can be far more dangerous by compressing the spinal cord. Cervical canal stenosis may lead to myelopathy, a serious conditions causing symptoms including major body weakness and paralysis.[12] Such severe spinal stenosis symptoms are virtually absent in lumbar stenosis, however, as the spinal cord terminates at the top end of the adult lumbar spine, with only nerve roots (cauda equina) continuing further down.[13] Cervical spinal stenosis is a condition involving narrowing of the spinal canal at the level of the neck. It is frequently due to chronic degeneration,[14] but may also be congenital or traumatic. Treatment frequently is surgical.[14]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of spinal stenosis involves a complete evaluation of the spine. The process usually begins with a medical history and physical examination. X-ray and MRI scans are typically used to determine the extent and location of the nerve compression.

Medical history

The medical history is the most important aspect of the examination as it will tell the physician about subjective symptoms, possible causes for spinal stenosis, and other possible causes of back pain.[15]

Physical examination

The physical examination of a patient with spinal stenosis will give the physician information about exactly where nerve compression is occurring. Some important factors that should be investigated are any areas of sensory abnormalities, numbness, irregular reflexes, and any muscular weakness.[15]

MRI

The MRI has become the most frequently used study to diagnose spinal stenosis. The MRI uses electromagnetic signals to produce images of the spine. MRIs are helpful because they show more structures, including nerves, muscles, and ligaments, than seen on x-rays or CT scans. MRIs are helpful at showing exactly what is causing spinal nerve compression.[15]

CT myelogram

A spinal tap is performed in the low back with dye injected into the spinal fluid. X-Rays are performed followed by a CT scan of the spine to help see narrowing of the spinal canal. This is a very effective study in cases of lateral recess stenosis. It is also necessary for patients in which MRI is contraindicated, such as those with implanted pacemakers.

Red flags

- Fever

- Nocturnal pain

- Gait disturbance

- Structural deformity

- Unexplained weight loss

- Previous carcinoma

- Severe pain upon lying down

- Recent trauma with suspicious fracture

- Presence of severe or progressive neurologic deficit [8]

Treatments

Treatment options are either or surgical or non-surgical . Overall evidence is inconclusive whether non-surgical or surgical treatment is the better for lumbar spinal stenosis.[16]

Non-surgical treatments

The effectiveness of non surgical treatments is unclear as they have not been well studied.[17]

- Education about the course of the condition and how to relieve symptoms

- Medicines to relieve pain and inflammation, such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Exercise, to maintain or achieve overall good health, aerobic exercise, such as riding a stationary bicycle, which allows for a forward lean, walking, or swimming can relieve symptoms

- Weight loss, to relieve symptoms and slow progression of the stenosis

- Physical therapy, to provide education and support for self-care. Also may give instructs on stretching and strength exercises that may lead to a decrease in pain and other symptoms[18]

- Lumbar epidural steroid or anesthetic injections have low quality evidence to support their use.[17][19][20]

Surgery

Lumbar decompressive laminectomy: This involves removing the roof of bone overlying the spinal canal and thickened ligaments in order to decompress the nerves and sac of nerves. 70-90% of people have good results.[21]

- Interlaminar implant: This is a non-fusion U-shaped device which is placed between two bones in the lower back that maintains motion in the spine and keeps the spine stable after a lumbar decompressive surgery. The U-shaped device maintains height between the bones in the spine so nerves can exit freely and extend to lower extremities.[22]

- Surgery for cervical myelopathy is either conducted from the front or from the back, depending on several factors such as where the compression occurs and how the cervical spine is aligned.

- Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A surgical treatment of nerve root or spinal cord compression by decompressing the spinal cord and nerve roots of the cervical spine with a discectomy in order to stabilize the corresponding vertebrae.

- Posterior approaches seek to generate space around the spinal cord by removing parts of the posterior elements of the spine. Techniques include laminectomy, laminectomy and fusion, and laminoplasty.

Epidemiology

- Swedish study defined spinal stenosis as a canal of 11mm or less found an incidence of 5 per 100,000 inhabitants.

- National Low Back Pain Study recorded that out of 2,374 patients with low back pain, 35% had bone related spinal nerve compression.[citation needed]

- Data from National Ambulatory Medical Care survey suggests 13-14% of patients with low back pain may have spinal stenosis.[citation needed]

- The NAMCS data shows the incidence in the U.S. population to be 3.9% of 29,964,894 visits for mechanical back problems.[23]

- The Longitudinal Framingham Heart Study found 1% of men and 1.5% of women had vertebral slippage at mean age of 54. Over the next 25 years, 11% of men and 25% of women developed degenerative vertebral slippage.[24]

- 250,000-500,000 U.S. residents have symptoms of spinal stenosis.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b Vokshoor A (February 14, 2010). "Spinal Stenosis". eMedicine. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ "Fast Facts About Spinal Stenosis". Niams.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ^ a b c d e Mazanec D.J.; Podichetty V.K.; Hsia A. (2002). "Lumbar Canal Stenosis: Start with nonsurgical therapy". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 69 (11).

- ^ "What is CSM?". Myelopathy.org. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ^ "Cervical Radiculopathy (Pinched Nerve)". AAOS. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ a b c Costantini A.; Buchser E.; Van Buyten J.P. (2009). "Spinal Cord Stimulation for the Treatment of Chronic Pain in Patients with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis". Neuromodulation. 13 (4): 275–380. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1403.2010.00289.x.

- ^ a b Goren A.; Yildiz N.; Topuz O.; Findikoglu G.; Ardic F. (2010). "Efficacy of exercise and ultrasound in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: A prospective randomized controlled trial". Clinical Rehabilitation. 24 (7): 623–631. doi:10.1177/0269215510367539.

- ^ a b Doorly, T.P., Lambing, C.L., Malanga, G.A., Maurer, P.M., Ralph R., R. (2010). Algorithmic approach to the management of the patient with lumbar spinal stenosis. Journal of Family Practice, 59 S1-S8

- ^ Mazanec, D.J., Podichetty, V.K., Hsia, A. (2002) LumbarClinic Journal of Medicine 69(11).

- ^ "Spinal stenosis Causes". Mayo Clinic. 2012-06-28. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ^ Wu, Jau-Ching; Ko, Chin-Chu; Yen, Yu-Shu; Huang, Wen-Cheng; Chen, Yu-Chun; Liu, Laura; Tu, Tsung-Hsi; Lo, Su-Shun; Cheng, Henrich (2013-07-01). "Epidemiology of cervical spondylotic myelopathy and its risk of causing spinal cord injury: a national cohort study". Neurosurgical Focus. 35 (1): E10. doi:10.3171/2013.4.FOCUS13122.

- ^ "CSM Symptoms". Myelopathy.org. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ^ Waxman, SG (2000). Correlative Neuroanatomy (24th ed.).

- ^ a b Meyer F, Börm W, Thomé C; Börm; Thomé (May 2008). "Degenerative cervical spinal stenosis: current strategies in diagnosis and treatment". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 105 (20): 366–72. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2008.0366. PMC 2696878. PMID 19626174.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Cluett, Jonathan, M.D. (2010) Spinal Stenosis - How is Spinal Stenosis Diagnosed?

- ^ Zaina, F; Tomkins-Lane, C; Carragee, E; Negrini, S (29 January 2016). "Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 1: CD010264. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010264.pub2. PMID 26824399. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ a b Ammendolia, C; Stuber, KJ; Rok, E; Rampersaud, R; Kennedy, CA; Pennick, V; Steenstra, IA; de Bruin, LK; Furlan, AD (30 August 2013). "Nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis with neurogenic claudication". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 8: CD010712. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010712. PMID 23996271.

- ^ "Lumbar Spinal Stenosis-Treatment Overview". Webmd.com. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ^ Manchikanti, L; Kaye, AD; Manchikanti, K; Boswell, M; Pampati, V; Hirsch, J (February 2015). "Efficacy of epidural injections in the treatment of lumbar central spinal stenosis: a systematic review". Anesthesiology and pain medicine. 5 (1): e23139. doi:10.5812/aapm.23139. PMID 25789241.

- ^ Chou, R; Hashimoto, R; Friedly, J; Fu, R; Bougatsos, C; Dana, T; Sullivan, SD; Jarvik, J (25 August 2015). "Epidural Corticosteroid Injections for Radiculopathy and Spinal Stenosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 163: 373–81. doi:10.7326/M15-0934. PMID 26302454.

- ^ Malamut, edited by Joseph I. Sirven, Barbara L. (2008). Clinical neurology of the older adult (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 220. ISBN 9780781769471.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "coflex Interlaminar Technology - P110008". Fda.gov. 2014-01-17. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ^ "Spinal Stenosis Details". Spinalstenosis.org. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ^ Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, No. 32]. (2001). In AHRQ Archive. Retrieved 2/29/2012.

External links

- Uvm.edu

- Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Questions and Answers about Spinal Stenosis - US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases