The Founding Ceremony of the Nation

| The Founding Ceremony of the Nation | |

|---|---|

| Chinese: 開國大典, Pinyin: Kaiguo dadian | |

| |

| Artist | Dong Xiwen |

| Year | 1953. Revised 1954, 1967 |

| Type | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 229 cm × 400 cm (90 in × 160 in) |

| Location | National Museum of China, Beijing |

| The Founding Ceremony of the Nation | |

|---|---|

| Chinese: 開國大典, Pinyin: Kaiguo dadian | |

1979 revision | |

| Artist | Jin Shangyi and Zhao Yu after Dong Xiwen |

| Year | 1972. Revised 1979 |

| Type | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 227 cm × 398 cm (89 in × 157 in) |

| Location | National Museum of China, Beijing |

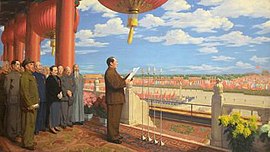

The Founding Ceremony of the Nation (Pinyin: Kaiguo dadian, Chinese: 开国大典) also called The Founding of the Nation is a 1953 oil painting by Chinese artist Dong Xiwen. The work depicts Mao Zedong and his close associates inaugurating the People's Republic of China in Tiananmen Square on October 1, 1949. One of the most-reproduced paintings of the People's Republic, it was repeatedly revised, even painted anew, as some of those it depicted fell from power, and later were rehabilitated.

After the communists took control of China, they sought to memorialize their struggle and triumph with artworks. Dong was assigned to paint a depiction of the October 1 ceremony, at which he had been present. He thought it essential that the painting both show the people and their leaders. After three months, he completed an oil painting in a folk art style, drawing upon Chinese art history for the contemporary subject. The success of the painting was assured when Mao viewed it and liked it, and it was reproduced in large numbers for display in the home.

The 1954 purge of Gao Gang from the government resulted in Dong being required to remove him from the painting. Gao's departure was not the last, as Dong was required to remove Liu Shaoqi in 1967. The winds of political fortune continued to shift, resulting in a new version of the painting being made in 1972 by other artists to accommodate another deletion. That replica was modified in 1979 to include the purged individuals, who had been rehabilitated. Both versions of the painting are in the National Museum of China in Beijing.

Background

Following the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949, communists quickly took control of art in China. The socialist realism that was characteristic of Soviet art came to be highly influential in the People's Republic. The new government proposed a series of paintings, preferably in oil, to memorialize the history of the Communist Party of China (CPC), and its triumph in 1949. To this end, in December 1950, arts official Wang Yeqiu proposed to deputy Minister of Culture Zhou Yang that there be an art exhibition the following year to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the founding of the Party in China. Wang had toured the Soviet Union and observed its art, with which he was greatly impressed, and he proposed that sculptures and paintings be exhibited depicting the CPC's history, for eventual inclusion in the planned Museum of the Chinese Revolution. Even before gaining full control of the country, the CPC had used art as propaganda, a technique especially effective as much of the Chinese population was then illiterate. Wang's proposal was preliminarily approved in March 1951, and a committee, including the art critic and official Jiang Feng, was appointed to seek suitable artists.[1] Although nearly 100 paintings were produced for the 1951 exhibition, not enough were found to be suitable, and it was cancelled.[2]

The technique of using oil paintings to memorialize events and make a political statement was not new; 19th century examples include John Trumbull's paintings for the United States Capitol and Jacques-Louis David's The Coronation of Napoleon.[3] Oil painting allowed for a multiple blending of tones and for a wide range of colors, yielding a realistic, attractive touch not possible with traditional Chinese ink and brush painting.[4] Wang had admired how, in Moscow museums, Lenin's career was chronicled and made accessible to the masses through artifacts accompanied by oil paintings showing crucial moments in the communist leader's career, and he and higher-level officials sought to do the same as they planned the Museum of the Chinese Revolution. Thus, they sought to chronicle the Party's history and showcase its accomplishments. Paintings were commissioned even though the museum did not yet exist, and did not open until 1961.[5]

None of the works initially obtained for the museum depicted the crowning moment of the revolution, the ceremony at Tiananmen Square on October 1, 1949 when Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic. Officials deemed such a work essential.[6] Dong Xiwen, as an accomplished and politically reliable artist, and as a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing, was an obvious candidate.[5] Although Dong later complained that never in his career had he been allowed to create the painting which was uppermost in his mind,[7] The Founding of the Nation would make him famous.[2]

Subject and techniques

The painting depicts the inaugural ceremony of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949. The focus is on Mao, who stands on Tiananmen Gate's balcony, reading his proclamation into (originally) two microphones.[8] Dong took some liberties with the appearance of Tiananmen Gate, opening up the space in front of Mao to grant the chairman a more direct connection with his people,[9] something that Liang Sicheng deemed an architectural mistake, but artistically brilliant.[2] Five doves fly into the sky to Mao's right. Assembled on the square before him are honor guards and members of patriotic organizations, in orderly ranks and with some holding banners. Qianmen, the gate at the south end of the square, is visible as well as an eastern gate which was later torn down. The new flag of China is seen over the people.[8] Beyond the old city walls that at the time enclosed the square (they were torn down in the 1950s) the city of Beijing is visible, and in the distance is represented the nation of China, with those further scenes under bright sunlight and sharply-defined clouds.[10] October 1 had been an overcast day in Beijing; Dong took artistic license with the weather.[11]

To Mao's left are seen his lieutenants in the communist takeover. In the original painting, the front row, which is ordered by rank, consisted of (from left) General Zhu De, Liu Shaoqi, Madame Song Qingling (the widow of Sun Zhongshan), Li Jishen, Zhang Lan (with beard) and at far right, General Gao Gang. Zhou Enlai is furthest left in the second row, and beside him are Dong Biwu, two men whose identities are uncertain, and furthest right, Guo Moruo. Furthest left in the third row is Lin Boqu.[8] These officials are surrounded by huge lanterns, a symbol of prosperity,[7] and the chrysanthemums on either side symbolize longevity. The doves represent peace restored to a nation long wracked by war.[9] The new five-star flag of China, rising over the people, represents the end of the feudal system and the rebirth of the nation as the People's Republic.[2] Mao, who is presented as a statesman, not as the revolutionary leader he was during the conflict, faces Qianmen, aligning himself along Beijing's North-South Axis, symbolizing his authority. The chairman is at the center of multiple, concentric circles in the painting, with the innermost formed by the front row of his comrades, another by the people in the square, and the outermost the old city walls. Beyond them are the sunlit scenes, envisioning a glorious future for China with Mao the heart of the nation.[12]

Although Dong had been trained in Western oil painting, he chose a folk art style for The Founding of the Nation, using bright, contrasting colors in a manner similar to that in New Year's prints popular in China. He stated in 1953, "the Chinese people like bright, intense colors. This convention is in line with the theme of The Founding Ceremony of the Nation. In my choice of colors I did not hesitate to put aside the complex colors commonly adopted in Western painting as well as the conventional rules for oil painting."[9] Red is present throughout the painting, lending a joyful, festive air to it, as well as giving "cultural sublimity", appropriate for a work depicting the founding of a nation.[13]

Dong drew upon Chinese art history, using techniques from Dunhuang murals of the Tang Dynasty, Ming Dynasty portraits, and ancient figure paintings. Patterns on the carpet, columns, lanterns, and railing evoke cultural symbols.[13] The colors of the painting are reminiscent of crudely-printed rural woodcuts; this is emphasized by the black outlines of a number of objects, including the pillars and stone railing, as those outlines are characteristic of such woodcuts.[14] Dong noted, "If this painting is rich in national styles, it is largely because I adopted these [native] approaches."[9]

Composition

The Founding of the Nation was one of several paintings commissioned for the new Museum of the Chinese Revolution from faculty members at CAFA. Two of these, Luo Gongliu's Tunnel Warfare and Wang Shikuo's Sending Him Off to the Army were completed in 1951; The Founding of the Nation was finished the following year.[15] These commissions were regarded as from the government, and were highly prestigious. State assistance, such as access to archives, was available.[16] At the time CAFA chose Dong to create the painting, he was at the Shijingshan power plant in the suburbs of Beijing, creating paintings depicting workers. Dong had been present at the October 1, 1949 ceremony; his personal connection to the event helped make him an appropriate choice. He was recalled to Beijing and put to work immediately creating the painting. Dong reviewed the photographs of the event, but found them unsatisfactory as none showed both the leaders, and the people gathered in the square below, which he felt was necessary. He created a postcard-size sketch, but was dissatisfied with it, feeling it did not capture the grandeur of the occasion. Through the advice of other artists, Dong made adjustments to his plan.[11]

Dong rented a small room in western Beijing above a grocery store selling soy sauce.[11] Jiang intervened to get Dong time and space to create the painting;[15] the painter needed three months to complete his work. The room was smaller than the painting, which is four meters across, and Dong would affix part of the canvas to the ceiling, working on his back. To save commuting time, he slept there in a chair, and was often chain smoking, with ashtrays full, as he worked on his project. His daughter brought him meals, but he often could not eat. Once the painting was perhaps seven or eight percent completed, Dong's friend, the oil painter Ai Zhongxin, and other artists, came to visit. In the discussions, they decided that the figure of Mao, the central one of the painting, was not tall enough. Dong carefully removed the figure of Mao from the canvas, and re-painted him, increasing his height by just under an inch (2.54 cm).[11]

In painting the sky and the pillars, Dong used a pen and brush, as if doing a traditional Chinese painting. He carefully designed the clothing worn by the people depicted; Madame Song wears gloves showing flowers, while Zhang Lan's silk robe appears carefully ironed for the momentous day.[17] He also used sawdust to enhance the texture of the carpet on which Mao stands.[9] Dong did not paint the marble railing as white, but yellowish, so as to emphasize the age of the Chinese nation.[2]

Reception and prominence

When the painting was unveiled in 1953, most Chinese critics were enthusiastic about it. Not all were, though. Xu Beihong, though admiring the manner in which the painting fulfilled its political mission, complained that because of the colors, it barely resembled an oil painting.[10] Zhu Dan, head of the People's Fine Arts Publishing House, which would reproduce the painting for the masses, argued that it was more a poster than an oil painting. Other artists stated that Dong's earlier works, such as Kazakh Shepherdess (1947) and Liberation (1949), were better examples of the new national style of art.[17] Senior Party leaders, though, approved of the painting, "seeing it as a testament to the young nation's evolving identity and growing confidence".[10]

Soon after the unveiling, Jiang wanted to arrange an exhibition at which government officials, including Mao, could view the new Chinese art. He had connections in Mao's inner circle, and Dong and others organized it to be in conjunction with meetings at Zhongnanhai that Mao led. This would prove the only time Mao attended an art exhibition after 1949. Mao visited the exhibition three times in between meetings and especially liked The Founding of the Nation—the official photograph of the event shows Mao and Zhou Enlai viewing the canvas with Dong. Mao stated that the portrayal of Dong Biwu was particularly well rendered. As Dong Biwu is in the second row, mostly hidden by the large Zhu De, Mao was most likely joking, but the favorable reaction by the country's leader assured the success of the painting.[18]

The Founding of the Nation was hailed as one of the the greatest oil paintings ever by a Chinese artist by reviewers in that country, and more than 500,000 reproductions were sold in three months.[7] Mao's praise helped boost the painting, and its painter. Dong's techniques were seen as bridging the gap between the elitist medium of oil paintings and popular art, and as a boost to Jiang's position that realistic art could be politically desirable.[14] It was reproduced in primary and secondary school textbooks.[2] The painting appeared on the front page of People's Daily in September 1953, and became an officially-approved nianhua, or interior decoration. One English-language magazine published by the Chinese government for distribution abroad showed a model family in a modern apartment, with a large poster of The Founding of the Nation on the wall.[19] According to art historian Chang-Tai Hung, the painting "became a celebrated propaganda piece".[20]

Later history

In February 1954, the head of the State Planning Council and the individual depicted in the original immediately on Mao's left, Gao Gang, was purged from government; he killed himself only months later. This placed arts officials in a quandary: given its popularity among officials and the people, The Founding of the Nation had to be shown at the Second National Arts Exhibition (1955), but it was unthinkable that Gao, deemed a traitor, should be depicted. Accordingly, Dong was ordered to excise Gao from the painting, which he did.[21]

In removing Gao, Dong expanded the basket of pink chrysanthemums which stands at the officials' feet, and completed the partial palace gate seen behind Gao. He was forced to expand the section of sky seen above the people assembled in Tiananmen Square, which affected the placement of Mao as the center of attention. He compensated for this, to some extent, by adding two more microphones to Mao's right. The painting was shown in this form in the 1955 exhibition, and in 1958 in Moscow. Julia Andrews, in her book on the art of the People's Republic, suggested that Dong's solution was not entirely satisfactory as the microphones dominate the center of the painting, and Mao is diminished by the expanded space around him. Although the painting was subsequently altered again and does not exist in this form, this version is the one most commonly reproduced.[21]

When the Museum of the Chinese Revolution opened in 1961, the painting was displayed on a huge wall in the gallery devoted to the communist triumph, but in 1966, during the Cultural Revolution, radicals shut down the museum, and it remained closed until 1969.[22] During that time, Liu Shaoqi, accused of taking a "capitalist road" was purged from government. His removal from the painting was ordered in 1967, and Dong was tasked to carry it out.[23] Dong had suffered during the Cultural Revolution: accused of being a rightist, he was expelled from the Party for two years, sent to work at a rural cadre school, and then was "rehabilitated" by being made to labor as a steelworker.[6] The task set Dong was difficult, as Liu is one of the most prominent figures in the first row, standing to the left of Madame Song. Officials wanted Liu replaced with Lin Biao, much in Mao's favor at the time. Dong was unwilling to put Lin in a place he had not occupied in real life, and, though he could not refuse outright at the chancy time of the Cultural Revolution, maneuvered so that the final order was merely Liu's removal. Liu's figure was too large to delete, so he was repainted as Dong Biwu, and made to appear as if in the second row. According to Andrews, the attempt was a failure, "the new Dong Biwu does not recede into the second row as intended. Instead, he appears as a leering, glowing figure, a strangely malevolent character in the midst of an otherwise stately group".[24] Officials deemed the revised work unexhibitable. Andrews speculated that Dong may have been trying to sabotage the change, or may have been affected by the stress of the years of the Cultural Revolution.[24]

In 1972, as part of a renovation of the Museum of the Chinese Revolution, officials wanted to exhibit Dong's painting again. However, they decreed that Lin Boqu, who stands at far left with white hair, must be removed.[24] This was because the Gang of Four, then in control of China, blamed Lin Boqu (who had died in 1960) for opposing the marriage, in the revolutionary days, of Mao with Jiang Qing (one of the Four). Sources differ on what took place regarding the painting: Chang-Tai Hung related that Dong, terminally ill with cancer, could not make the changes, so his student Jin Shangyi and another artist, Zhao Yu were assigned to do the work. The two feared damaging the original canvas, so made an exact replica but for the required changes, with Dong brought forth from his hospital for consultations.[23] According to Andrews, Dong would not let anyone else alter his painting, so Jin and Zhao created the new version.[24] Jin later stated that the painting is not only effective politically, it shows Dong's inner world.[13]

With the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 and the subsequent accession of Deng Xiaoping, many of the purged figures of earlier years were rehabilitated, and the authorities in 1979 decided to bring more historical accuracy to the painting. Dong had died in 1973; his family strongly opposed anyone altering the original painting, and the government respected their wishes. Jin was on a tour outside China, so the government assigned Yan Zhenduo to make changes to the replica. He placed Liu, Lin Boqu and Gao in the painting[23] and made other changes as well: a previously unidentifiable man in the back row now resembles the young Deng Xiaoping. The replica painting was restored to the Museum of the Chinese Revolution.[25]

The painting was reproduced on Chinese postage stamps in 1959 and 1999, for the tenth and fiftieth anniversaries of the founding of the People's Republic.[26] Also in 1999, the museum authorized a private company to make small-scale gold foil reproductions of the painting. Dong's family sued, and in 2002 the courts found that Dong's heirs held the copyright to the painting, and that the museum merely had the right to exhibit it.[27] Joe McDonald of Associated Press deemed this outcome " a triumph for China's capitalist ambitions over its leftist history".[28]

The painting has never been as highly regarded in the West as in China; according to Andrews, "art history students have been known to roar with laughter when slides of it appear on the screen".[18] Art historian Michael Sullivan dismissed it as mere propaganda.[18] Today, following a merger of museums, both paintings hang in the National Museum of China, on Tiananmen Square.[11][29]

See also

References and bibliography

Citations

- ^ Hung 2007, pp. 785–786.

- ^ a b c d e f Wu Jijin (January 4, 2011). "《开国大典》油画曾四次修改 哪些人被删除了?(Founding Ceremony painting has been modified four times: who was deleted?" (in Chinese). ifeng.com. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ Hung 2007, p. 785.

- ^ Hung 2007, p. 789.

- ^ a b Hung 2007, pp. 790–792.

- ^ a b Gao Jimin. "受党内斗争影响数遭劫难的油画《开国大典》(Founding Ceremony, an oil painting devastated several times by the conflict within the Party)" (in Chinese). Communist Party of China. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Hung 2007, p. 783.

- ^ a b c Andrews, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e Hung 2007, p. 809.

- ^ a b c Hung 2007, p. 810.

- ^ a b c d e "揭秘《开国大典》油画:增高毛泽东删除刘少奇 (Secret Founding Ceremony painting increased Mao Zedong, removed Lin Shaoqi)" (in Chinese). ifeng.com. April 19, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ Hung 2007, pp. 809–810.

- ^ a b c "Dong Xiwen, The Founding Ceremony". National Museum of China. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Andrews, p. 82.

- ^ a b Andrews, pp. 76–79.

- ^ Hung 2007, pp. 791–792.

- ^ a b Ai Zhongxin (March 24, 2008). "油画《开国大典》的成功与蒙难 (The success and difficulty of the oil painting Founding Ceremony)" (in Chinese). Bo Po Art Network. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Andrews, p. 80.

- ^ Andrews, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Hung 2005, p. 920.

- ^ a b Andrews, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Hung 2005, p. 931.

- ^ a b c Hung 2007, p. 784.

- ^ a b c d Andrews, p. 84.

- ^ Andrews, p. 85.

- ^ Kloetzel (editor), James E. (2006). Scott 2007 Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue: Volume 2 C–F. Sidney, OH: Scott Publishing Co. pp. 324, 365. ISBN 0-89487-376-8.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Zha Xin, Li Xu (December 28, 2002). "著名油画《开国大典》著作权案在京审结 (The famous painting Founding Ceremony copyright case concluded in Beijing" (in Chinese). Xinhua News Service. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ McDonald, Joe (December 29, 2002). "Artist's rights upheld in China". Associated Press. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Modern China". National Museum of China. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

Bibliography

Sources

- Andrews, Julia Frances (1994). Painters and Politics in the People's Republic of China, 1949-1979. Berkeley CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520079816.

- Hung, Chang-Tai (December 2005). "The Red Line: Creating a Museum of the Chinese Revolution". The China Quarterly (184): 914–933. JSTOR 20192545.

- Hung, Chang-Tai (October 2007). "Oil Paintings and Politics: Weaving a Heroic Tale of the Chinese Communist Revolution". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 49 (4): 783–814. JSTOR 4497707.