Diné CARE

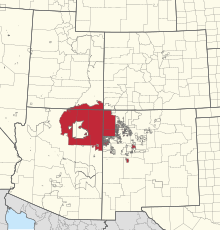

Diné CARE is a Diné (Navajo) activist organization that works on environmental, cultural and social justice campaigns, primarily within the Navajo Nation and the immediately surrounding areas. Diné CARE stands for Diné Citizens Against Ruining Our Environment and helped build the early environmental justice movement in the United States. Their work has included opposing the creation of toxic waste infrastructure, polluting energy infrastructure, industrial-scale logging, advocating for compensation for people impacted by uranium mining and weapons development as well as against business practices that facilitate abuse of alcohol in nearby Gallup.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

History

Originally called only CARE, the group was founded in 1988 to prevent the construction of a hazardous waste incinerator in the community of Dilkon on the Navajo Nation.[1][2] CARE's activism also led to the creation of the annual Protecting Mother Earth conferences. The first was held in Dilkon in 1990, funded by Greenpeace and Seventh Generation Fund. The creation of Indigenous Environmental Network came out of the Protecting Mother Earth gatherings in Dilkon, and in 1991, in South Dakota.[2][7]

CARE became Diné CARE at a 1991 meeting in Gallup that brought together activists from the Dilkon anti-incinerator activism with other activism taking place across the Navajo nation including alcohol use in Gallup, oil and gas exploration, uranium mining, logging, and asbestos dumping.[1] Co-founders included Lori Goodman, Leroy Jackson, Adella Begaye, Early Tulley and others. Leroy Jackson, who received death threats in response to his work to reform the logging industry's operations on the Chuska Mountains, died in 1994. Friends, family and colleagues believe he may have been murdered for his activism.[8][9]

See also

- Environmental justice

- Indigenous Environmental Network

- Navajo

- Navajo Nation

- Traditional ecological knowledge

References

- ^ a b c "Land, Wind, and Hard Words". University of New Mexico Press. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ a b c "From the Ground Up". NYU Press. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ Cabrera, Yvette (2022-11-30). "Nuclear buildup sickened his community. Then it caught up with him". Center for Public Integrity. Retrieved 2024-02-25.

- ^ Powell, Dana E. (2018). Landscapes of Power: Politics of Energy in the Navajo Nation. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-6994-3.

- ^ "Power Lines | Princeton University Press". press.princeton.edu. 2014-10-26. Retrieved 2024-02-26.

- ^ "Navajo Sacred Places". Indiana University Press. Retrieved 2024-03-19.

- ^ "About | Indigenous Environmental Network". www.ienearth.org. 2012-12-30. Retrieved 2024-03-19.

- ^ Kaufman, Leslie (1994-02-13). "Loggers, Witches, and the Death of a Navajo Eco-Warrior : Angered by the Rape of His Beloved Forest, Leroy Jackson Began Asking Questions About the Management of a Navajo Sawmill". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-03-19.

- ^ Selcraig, Bruce (October 26, 1994). "After Navajo Activist's Death, Mystery and Mission Among the Pines". Washington Post. pp. A-03.

Further readings

- Cabrera, Yvette. 2023. "Nuclear buildup sickened his community. Then it caught up with him." The Center for Public Integrity, November 30.

- Cole, Luke W. and Sheila R. Foster. (2000) From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. New York: NYU Press.

- Kaufman, Leslie. (1994). "Loggers, Witches, and the Death of a Navajo Eco-Warrior : Angered by the Rape of His Beloved Forest, Leroy Jackson Began Asking Questions About the Management of a Navajo Sawmill." Los Angeles Times, Feb. 13.

- Needham, Andrew. (2014). Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modern Southwest. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Powell, Dana E. (2015). "The rainbow is our sovereignty: Rethinking the politics of energy on the Navajo Nation." Journal of Political Ecology, vol. 22.

- Powell, Dana E. (2018). Landscape of Power: Politics of Energy in the Navajo Nation. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Selcraig, Bruce. (1994). "After Navajo Activist's Death, Mystery and Mission Among the Pines." Washington Post, October 26, A-03.

- Sherry, John W. (2010). Land, Wind and Hard Words: A Story of Navajo Activism. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

External links

[[Category:Navajo]] [[Category:Environmental justice]] [[Category:Activism]]