Jean de Venette

Jean de Venette | |

|---|---|

| Born | Jean de Venette c. 1307 |

| Died | aft. 1370 |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation(s) | French Chronicler Carmelite friar |

Jean de Venette (c. 1307–c. 1370) was a French chronicler and a Carmelite friar who wrote of the events surrounding him during the period of the Hundreds Years' War. He was the Prior of the Carmelite monastery in the Place Maubert, Paris, and was a Provincial Superior of France from 1341 to 1366.[1]

The Chronicle

The Chronicle is a narrrative of several historical events spanning the years of 1340 and 1368, written as early as 1340, until Jean de Venette’s death at or soon after the year 1368. When it was first published in the Spicilegium, vol. 3, it was published with another chronicle by William of Nangis. The Chronicle was later translated into English by Jean Birdsall, and was published under the same title in 1953. As many of the portions were recorded contemporaneously[2] and in a chronological fashion, it gives a very reliable first hand account of several historical events. A copy is in the form of a Manuscript on vellum from the mid-fifteenth century, containing 232 pages written in letters in columns. The titles are in red, and the letters painted in gold & turners in color. It is decorated with seven miniatures that are in monochrome gray.[3]

A more recent translation, The Chronicle of Jean de Venette, by Jean Birdsall, late Associate Professor of History Vassar College, Edited by Richard A. Newhall, Brown Professor of European History Williams College, holds the opinion that Guillaume (William) de Nangis is neither the primary chronicler nor the Second Continuator, so, although there is a conflicting opinion as to the later authorships, Jean de Venette seems to be the primary chronicler. The facts seem to indicate a dual authorship from 1340 to 1368.[4] During the years 1358-1359 the entries were contemporary with the events recorded; the earlier portion of the work, if it was begun as early as 1340, was subjected to revision later, though Venette himself states on the first page of his chronicle (1340) he is recording events "...in great measure as I have seen and heard them."[5]

The Chronicle begins in the year 1340 at which time Jean de Venette talks about the revelations of a (unnamed) priest who was held prisoner by the Saracens for 13 years and freed in 1309 who foretold of a vison of a great famine which would occur in 1315 and other horrible things which were to happen thereafter. Venette states that he was seven or eight in this year and indeed the famine did occur exactly as predicted and lasted two years. He then tells the background of the fight for the crown of France after the death of Philip the Fair and the claims of Edward I of England to that throne, thus describing the background to the beginning of the Hundred Years' War. His history is detailed and precise. He also describes the Battle of Crecy in 1356, The Peasant's War, and the siege of Calais, again with great detail.[6]

His time and his work

What is noteworthy and perhaps unique about Jean de Venette's work is that he had a great understanding and sympathy for the peasants. Most chroniclers wrote from the perspective of the nobles. There can be no doubt that his own humble beginnings afforded him a unique understanding of the hard life of these peasants.[7] His work covers many important events of the fourteenth century including, The Black Plague, the The Hundred Years' War and The Peasant's War. He had a master in theology from the University of Paris and spent a great deal of his time promoting study among the younger members of the Carmelite Order, and he gathered information on the earlier history of the Carmelite Order going all the way back to Elijah, its Founder. Venette regarded ignorance as the cause of many of the problems of his time, including the Black Death and encouraged many of the Carmelites to learn to read and write.[8]

The formulation of his beliefs and writings

Venette first and foremost followed the teachings of the Pope. No matter the person or the circumstances, he did not deviate from his religious beliefs and criticised anyone who was Excommunicate or otherwise not following the teachings of God. As did others in his time, Venette combines his religious belief with astronomical events. He quotes and agrees with the interpretation of Master Jean de Murs and others made before and during this time. It is clear that he, (as did other monastic chroniclers and monastic astronomers) attribute these signs as a "warning" from God that punishment was coming for Man's sinful nature.[9] In 1340, he speaks of a comet that appeared in that year. Another comet, still unidentified, was said to appear in August of 1348 which Venette himself sees.[10] This comet is also mentioned by Augustine of Trent, a friar eremite of St. Augustine who, in his writings, sees the later one as a warning of the disease and pestilence of disease happening in Italy, and blames the physicians' for their ignorance of astronomy. Due to his many references in the Chronicle, it is almost certain that de Venette agreed with Augustine. Venette also refers to passages from the Book of Revelations to try to understand and explain the chaos in and around him.[11]

The Plague

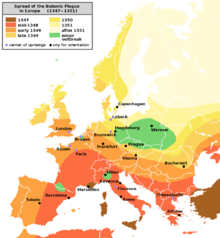

The Black Plague, the Black Death, or the Plague refers to the devastating disease which first appeared in Europe in 1348. Where it originated from is still debated but Venette attributes its origin to the "unbelievers". According to de Venette and others, within a short time, over 500 dead per day were being buried. It lasted approximately one year but returned in later years. While Jean observes how many "timid" priests did not do their religious duty to visit the dying and administer the Last Sacraments, he adds that the Sisters of the Hôtel-Dieu ... who, not fearing to die, nursed the sick in all sweetness and humility and many of them died themselves from the plague.[12]

The Hundred Years War

Jean vividly describes several battles of the Hundred Years' War such as the Battle of Crecy, the siege of Calais and the Battle of Poitiers.

Of the Battle of Crecy, de Venette places the time and day on "Saint Louis's Day, 1346, at the end of the ninth hour". He mentions the failure of the Genoese crossbows to function, he states they were useless because they were wet and not given time to dry out. He states that the French King ordered the massacre of the crossbowmen because of what he conceived as cowardice. He blames this and the further disorder and confusion of the French on the "undue haste" of the French King. He describes the English longbowmans' arrows as "rain coming from heaven and the sky's which were formerly clear, suddenly darkened".[13]

Venette was known as a child of the people, and until later in his life, he consistently acknowledged the power of the monarchy. He does not, however, hesitate to criticise the nobles for their failure to protect the people, particularly after the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 at which time the King of France and his son were taken hostage and held for an enormous ransom.

After the Battle of Poiters, many of the nobles and the "Companies" were ravaging the different towns and cities, pillaging and raping. Of that time Venette states: "...Thus discord and all three estates abandoned the task they had begun. From that time on, all went ill with the kingdom and the State was undone. Thieves and robbers rose up everywhere in the land. The Nobles despised and hated all others and took no thought for usefulness and profit of lord and men. They subjected and despoiled the peasants and the men of the villages. In no wise did they defend their country from it's enemies; rather did they trample it underfoot, robbing and pillaging the peasants' goods. The regent, it appeared, clearly gave no thought to their plight. At that time the country and the whole land of France began to put in confusion and mourning like a garment, because it had no defender or guardian..." .[14]

The Peasant's War

Jean de Venette also speaks about the Peasant’s War (part of the Hundred Years' War) in France. In one particular account, he tells of how a ragtag group of French peasants, led by Guillaume l'Aloue defeated the English in several skirmishes. After the capture of the French King by the English during the Battle of Poitiers in September 1356, power in France devolved fruitlessly among the States General, Charles the Bad, King of Navarre, and John's son, the Dauphin, later Charles V.

The Three Marys or Maries

The Three Marys is a long poem written circa 1357 by Jean de Venette.[15] The three Marys spoken of are: Mary, Mother of Our Lord, Mary Cleophas and Mary Salome of St. Palaye.[3][16] The Three Marys is in the form of a Manuscript (shown above) on vellum from the mid-fifteenth century.[4][17]

The Three Marys have been featured in numerous pieces of art and literature, including the Melisende Psalter, El Greco's Disrobing of Christ and Peter von Cornelius's The Three Marys at the Tomb, among others. The Eastern Orthodox Church especially celebrates them, and numerous icons represent them.

References

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 11th ed. Cambridge University Press/

- ^ Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) line 4-5

- ^ a b Le manuscrit médiéval ~ The Medieval Manuscript Nov. 2011 pg. 1

- ^ a b Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) Introduction

- ^ Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) chpt. (1340) p. 1)

- ^ Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953)

- ^ Calmette, L'Elaboration de mone moderne, p. 44

- ^ Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) p. 3-5.

- ^ Fernandez-Arnesto Felipe University of Paris Medical Facility, Writings on the Plague. The World: A History. vol. two.

- ^ Science News Magazine/

- ^ Book of Revelations

- ^ The History Guide Lectures of Ancient and medieval History /

- ^ Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) p.43

- ^ Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) p.66

- ^ The Medieval Manuscript. Monday, December 12, 2011

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle, p. 912. Note: Historian Regis Rech maintains there were two Jean de Venettes and the author of the poem, The Three Maries or Marys was not the Jean de Venette of the Chronicle.

- ^ Le manuscrit médiéval ~ The Medieval Manuscript Nov. 2011 p. 1

External links and Further Reading

- Jean de Venette, LoveToKnow Free Online Encyclopedia, Sep 2006, 20 Feb 2008, http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Jean_De_Venette.

- John Aberth, The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350,(Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005) 82-83.

- P.M. Rogers, Aspects of Western Civilization,(Prentice Hall, 2000), 353-365

- "Peasants at War in France: Guillaume l'Aloue in 1359," De Re Militari: The Society for Medieval Military History, ed. Peter Konieczny, 23 Feb 2008, http://www.deremilitari.org/resources/sources/peasantsfrance.htm

- John Aberth, The Black Death: The Great Mortality of 1348-1350,(Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005) 82-83.

- P.M. Rogers, Aspects of Western Civilization,(Prentice Hall, 2000), 353-365

- "Peasants at War in France: Guillaume l'Aloue in 1359," De Re Militari: The Society for Medieval Military History, ed. Peter Konieczny, 23 Feb 2008, http://www.deremilitari.org/resources/sources/peasantsfrance.htm>