First Battle of Memphis

| First Battle of Memphis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of American Civil War | |||||||

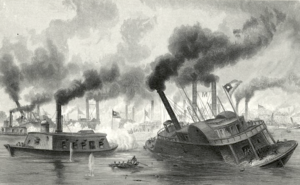

Battle of the rams. Ward, A. R., artist | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Charles Henry Davis Charles Ellet Jr. † |

James E. Montgomery M. Jeff Thompson | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Benton Louisville Carondelet Cairo St. Louis Ram Queen of the West Ram Monarch Ram Lancaster Ram Switzerland |

CSS General Beauregard CSS General Bragg CSS General Sterling Price CSS General Earl Van Dorn CSS General M. Jeff Thompson CSS Colonel Lovell CSS General Sumter CSS Little Rebel | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

5 ironclads 4 rams | 8 rams | ||||||

The First Battle of Memphis was a naval battle fought on the Mississippi River immediately above the city of Memphis, Tennessee on June 6, 1862, during the American Civil War. The engagement was witnessed by many of the citizens of Memphis. It resulted in a crushing defeat for the Confederate forces, and marked the virtual eradication of a Confederate naval presence on the river. Despite the lopsided outcome, the Union Army failed to grasp its strategic significance. Its primary historical importance is that it was the last time civilians with no prior military experience were permitted to command ships in combat. As such, it is a milestone in the development of professionalism in the United States Navy.[1]

Background

The defending Confederates closely matched the advancing federal force in raw numbers, with eight rebel vessels opposing nine Union gunboats and rams, but the fighting qualities of the former were far inferior. Each was armed with only one or two guns, of a light caliber that would be ineffective against the armor of the gunboats. The primary weapon of each was its reinforced prow, which was intended to be used in ramming opponents.[2]

The Confederate rams were distinguished by a unique feature of their defense against enemy shot. Their engines and other interior spaces were protected by a double bulkhead of heavy timbers, covered on the outer surface by a layer of railroad iron. The gap between the bulkheads, a space of 22 in (56 cm), was packed with cotton.[3] Although the cotton was the least important part of the armor, it caught the public's attention, and the boats came to be called "cottonclads". Later in the war, ships' crews were often protected from small-arms fire by bales of cotton placed in exposed positions, and these vessels were also referred to as "cottonclads". They differed, however, from the originals of the category.[2]

The federal force consisted of five gunboats, four of which were known semi-officially as "Eads gunboats", after their builder, James Buchanan Eads, but more commonly as "Pook turtles", after their designer, Samuel M. Pook, and their strange appearance.[4] The fifth gunboat, flagship Benton, was also a product of the Eads shipyards, but was converted from a civilian craft. Each of these vessels carried from 13–16 guns. The other four vessels were naval rams from the United States Ram Fleet. They had no armament whatever, aside from the small arms carried by the officers. All of the rams had been converted from civilian riverboats and had no common design.[2][5]

Organization

Both sides entered the battle with faulty command structures. The federal gunboats were members of the Mississippi River Squadron, commanded directly by Flag Officer Charles H. Davis, who reported to Major General Henry W. Halleck. The gunboats were thus a part of the United States Army, although their officers were supplied by the navy.[6] The rams were led by Colonel Charles Ellet, Jr., who reported directly to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton.[7] Thus the federal "fleet" consisted of two independent organizations, with no common command outside of Washington.

The Confederate arrangement was even worse. The cottonclads were about half of a group of fourteen river steamers that had been seized at New Orleans and converted into rams to defend that city. Known as the "River Defense Fleet", it was split in two when the Confederate holdings on the river became threatened from both the north and the Gulf of Mexico. Six were retained below New Orleans to face the fleet of David G. Farragut, while eight were sent up to Memphis to block the Union descent down the river. Sending them this far north did not violate their original purpose, as Memphis was regarded as a shield for New Orleans. The northern (Memphis) section was commanded overall by James E. Montgomery, a riverboat captain in civilian life. The other boats were also commanded by former civilian riverboat captains, selected by Montgomery, and with no military training. Once under way, Montgomery's command ceased, and the rams operated independently. The futility of this arrangement was recognized immediately by military men, but their protests were disregarded.[8] Furthermore, the captains would neither learn how to handle the guns themselves, nor assign crew members to the task, so gun crews had to be drawn from the Confederate Army. The gunners were not integrated into the crews, but remained subject to the orders of their army officers.[9]

Cottonclad River Defense Fleet

-

{Ex CSS} USS General Bragg probably photographed at Cairo or Mound City, Illinois, circa 1862–63. -

{Ex CSS} USS General Price off Baton Rouge, LA, January 18, 1864

Battle

As a result of the federal victory at Corinth, the railroads that linked Memphis with the eastern part of the Confederacy had been cut, severely reducing the strategic importance of the city. Therefore, in early June 1862, Memphis and its nearby forts were abandoned by the rebel army. Most of the garrison were sent to join units elsewhere, including Vicksburg and only a small rear guard was left to make a token resistance. The River Defense Fleet was also to have retreated to Vicksburg, but it could not get enough coal in Memphis. Unable to flee when the federal fleet appeared on June 6, Montgomery and his captains had to decide whether to fight, or scuttle their boats. They chose to fight, steaming out in the early morning to meet the advancing flotilla and the rams trailing behind it, with Memphis citizens cheering them on.[10]

The battle started with an exchange of gunfire at long range, the federal gunboats setting up a line of battle across the river and firing their rear guns at the cottonclads coming up to meet them as they entered the battle stern first. Two of the four rams advanced beyond the line of the gunboats and rammed or otherwise disrupted the movements of their opponents; the other rams misinterpreted their orders and did not enter the battle at all. With the federal rams and gunboats not coordinating their movements and the Confederate vessels operating independently, the battle soon was reduced to a melee. It is agreed by all that the ram flagship, Queen of the West, initiated hostilities by slamming into CSS Colonel Lovell. She was then rammed in turn by one or more of the remaining cottonclads. Ellet was at this time wounded by a pistol shot in his knee, thereby becoming the only casualty on the Union side. (In the hospital, he contracted measles, the childhood disease that killed some 5,000 soldiers during the war. The combination of the disease and the debilitation caused by his wound was too great, and he died on June 21.[11]) The remainder of the battle is obscured by more than the fog of war. Several eyewitness accounts are available; however, they are mutually contradictory to a greater degree than usual.[12] All that is certain is that at the end of the battle, all but one of the cottonclads were either destroyed or captured, and one Yankee boat, Queen of the West, was disabled. The sole boat to escape, CSS General Earl Van Dorn, fled to the protection of the Yazoo River, just north of Vicksburg.

Results

The battle, which took less than two hours in the early morning hours of June 6, resulted in the immediate surrender of the city of Memphis to federal authority by noon that day.

The Confederate casualties totaled approximately 100 killed or wounded and another 150 taken prisoner. The Union forces captured and repaired the CSS General Price, the CSS General Bragg, the CSS Sumter and CSS Little Rebel and entered them into the Mississippi River Squadron.[13]

The battle of Memphis was, aside from the later appearance of the ironclad CSS Arkansas, the final challenge to the federal thrust down the Mississippi River against Vicksburg. The river was now open down to that city, which was already besieged by Farragut's ships, but the federal army authorities did not grasp the strategic importance of the fact for nearly another six months. Not until November 1862 would the Union Army under Ulysses S. Grant attempt to complete the opening of the river.[2]

The poor performance of the River Defense Fleet, both at Memphis and at the earlier Battle of New Orleans, was the final demonstration that naval operations had to be commanded by trained professionals subject to military discipline.[2] The Ellet Rams remained in federal service, but they had no other opportunity for combat of the sort for which they were intended. They were soon transformed into an amphibious raiding body, the Mississippi Marine Brigade (with no connection to the United States Marine Corps), led by Ellet's brother, Lieutenant Colonel (later Brigadier General) Alfred W. Ellet. The demand for increased professionalism also resulted in the elimination of privateering,[14] although the River Defense Fleet was not composed of privateers in the usual meaning of the term.

The battle remains a cautionary tale, demonstrating the ill effects of a poor command structure. It is also one of only two purely naval battles of the war,[citation needed] excluding single-ship actions, and took place 500 mi (800 km) from the nearest open water. The other was the Battle of Plum Point Bend, also on the Mississippi.

Another civil war military engagement took place in Memphis, namely the Second Battle of Memphis in April 1864, when Confederate general, Nathan Bedford Forrest led a nighttime cavalry raid of Memphis with the intent of freeing Confederate prisoners and capturing Union generals encamped there. The raid failed in both goals, but forced the Union Army to guard the area more diligently.

See also

References

- ^ Abbreviations used in this article: ORA---War of the Rebellion; a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 volumes in four series; Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1880—1901. ORN--Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 30 volumes in two series; Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1894—1922.

- ^ a b c d e Groce, W. Todd, Battle of the Rams, North & South - The Official Magazine of the Civil War Society, Issue 4, Page 24.

- ^ ORA I, v. 52/1, pp. 37–38.

- ^ ORA III, v. 2, p. 815.

- ^ ORN I, v. 23, p. 34.

- ^ ORN I, v. 22, p. 280.

- ^ ORN I, v. 23, p, 75.

- ^ ORA I, v. 6, p. 817.

- ^ ORA I, v. 10/1, p. 589; ORN I, v. 23, p. 699.

- ^ ORA I, v. 52/1, pp. 37–40.

- ^ ORA I, v. 17, p. 9.

- ^ At least five independent accounts of the battle exist: ORN I, v. 23, pp. 119–121, 125–135, 136–138, 139–140; ORA I, v. 10/1, pp. 912–913, 925–927, with some repetitions.

- ^ Bearss, Edwin C. (1966). Hardluck Ironclas: The Sinking and Salvage of the Cairo. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8071-0684-6. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ Robinson, Confederate privateers, p. 1; Luraghi, History of the Confederate Navy, p. 71.

Further reading

- National Park Service battle description

- CWSAC Report Update

- Anderson, Bern. By sea and by river: the naval history of the Civil War. New York: Da Capo Press, 1962.

- Crandall, Warren Daniel, History of the Ram Fleet and the Mississippi Marine Brigade in the War for the Union on the Mississippi and its tributaries: the story of the Ellets and their men, Press of the Buschart Brothers, 1907.

- Hearn, Chester G. Ellet's Brigade: the strangest outfit of all. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

- Johnson, Robert Underwood, and Buel, Clarence Clough, eds. Battles and leaders of the Civil War. Secaucus, New Jersey, n.d.; reprint ed., New York: Century, 1887, 1888.

- Joiner, Gary D., Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy - The Mississippi Squadron, Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2007.

- Luraghi, Raimondo.A history of the Confederate Navy (translated by Paolo E. Coletta). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1996.

- Musicant, Ivan. Divided waters: the naval history of the Civil War. New York: HarperCollins, 1995.

- Robinson, William Morrison Jr. The Confederate privateers. Yale University, 1928. Reprint, Univ. of South Carolina, 1990.

- Scharf, J. Thomas. History of the Confederate States Navy from its organization to the surrender of its last vessel. New York: Gramercy, 1996; reprint ed., New York: Rogers and Sherwood, 1887.

External links

- Battles of the Joint Operations Against New Madrid, Island No. 10, and Memphis of the American Civil War

- Battles of the Western Theater of the American Civil War

- Naval battles of the American Civil War

- Union victories of the American Civil War

- Battles of the American Civil War in Tennessee

- History of Memphis, Tennessee

- 1862 in the American Civil War

- 1862 in Tennessee

- June 1862 events

- Riverine warfare

- United States Ram Fleet