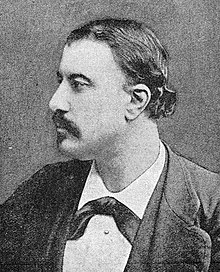

Frederic Clay

Frederic Emes Clay (3 August 1838 – 24 November 1889) was an English composer known principally for his music written for the stage. Clay, a great friend of Arthur Sullivan's, wrote four comic operas with W. S. Gilbert and introduced the two men.

While working as a civil servant in the Treasury department, Clay began composing seriously in the early 1860s. His first big success was Ages Ago (1869), a short comic opera with a libretto by W. S. Gilbert, for the small Gallery of Illustration. Other pieces with Gilbert and others followed, and Clay turned to composing full-time after his father died in 1873. That year, he composed a successful opera-bouffe version of The Black Crook for the Alhambra Theatre. Clay's last piece with Gilbert was Princess Toto (1875). He also composed two cantatas. His last two works were both successful operas composed in 1883, The Merry Duchess and The Golden Ring. He then suffered a stroke that paralysed him at age 44.

Life and career

Clay was born in Paris[1] to English parents, James Clay (1804–1873), a member of parliament, and his wife, Eliza Camilla Woolrych. Clay was the fourth of six brothers and sisters. His father was celebrated as a player of whist and the author of a treatise on that subject, as well as an amateur composer. His mother also had a musical background, as her mother had been an opera singer.[2] Clay was educated at home by private tutors in London, studying piano and violin, and then music composition under Bernhard Molique and, in 1863, with Moritz Hauptmann in Leipzig, Germany.[3] He then worked as a civil servant in the Treasury department while also pursuing composing.[4]

After the death of his father in 1873, his inheritance enabled him to become a full-time composer.[5] With the exception of some songs, hymns, instrumental pieces and two cantatas, his compositions were nearly all written for the stage. In the mid-1860s, Clay and his friend Arthur Sullivan became frequent guests at the home of John Scott Russell. By about 1865, Clay became engaged to Scott Russell's youngest daughter Alice, and Sullivan wooed the middle daughter Rachel. The Scott Russells welcomed the engagement of Alice to Clay, but he broke it off.[6]

Early career

Clay wrote his first short play for the amateur stage in 1859 called 'The Pirate's Isle, and completed the short comic play Out of Sight the following year.[4] His first professionally produced piece was an opera entitled Court and Cottage, with a libretto by Tom Taylor, which was produced at Covent Garden Theatre in 1862. In 1865, for the same theatre, he composed another opera, the unsuccessful Constance (1865), with a libretto by Thomas William Robertson.[7] With B. C. Stephenson, he wrote three pieces played by amateurs: The Pirate's Isle, Out of Sight and The Bold Recruit (1868), and with W. S. Gilbert he wrote Ages Ago (1869) for Thomas German Reed's Gallery of Illustration.[3] This piece ran for 350 performances and was revived several times.[5] Clay introduced Gilbert to Arthur Sullivan during a rehearsal for Ages Ago.[8] The Bold Recruit was revived at a benefit by German Reed at the Gallery of Illustration in 1870 as a companion piece to Ages Ago.[9]

These were followed by The Gentleman in Black (1870, also with Gilbert), In Possession (1871, also for German Reed), Happy Arcadia (1872, with Gilbert), Oriana (1873, with a libretto by James Albery), Green Old Age and Cattarina (both 1874, with libretti by Robert Reece), Princess Toto (1876, the last collaboration between Clay and Gilbert), and Don Quixote (1876).[5] Ages Ago (a one-act piece) and Princess Toto (a three-act comic opera) are considered to be among Clay's most tuneful and attractive works. The Times wrote that the music of Princess Toto "is probably surpassed by no modern English work of the kind for gaiety and melodious charm."[10]

Clay also composed part of the score for the spectacle Babil and Bijou (1872, also for German Reed)[10] and the successful opera-bouffe version of The Black Crook (1873 based on the same source material as the earlier American musical of the same name and starring Kate Santley), both of which were produced with success at the Alhambra Theatre. He also furnished incidental music for a revival of Twelfth Night.[4]

Cantatas and later career

Clay's two cantatas were The Knights of the Cross (1866) and Lalla Rookh (containing perhaps Clay's best-known song, "I'll sing thee songs of Araby" and also "Still this golden lull"), which was produced successfully at the Brighton Festival in 1877.[3] Clay had difficulty finding work in London and moved to America. There he met with only mixed success and returned to England in 1881.[2] His last works were The Merry Duchess (1883) at the Royalty Theatre, starring Kate Santley and in which Louie Henri also appeared,[11][12] and The Golden Ring (starring Marion Hood) (1883), both with words by G. R. Sims. The latter was written for the reopening of the Alhambra, which had been burned to the ground the year before.[13] These shows were both successful and showed an artistic advance upon Clay's previous work.[14]

Clay's friend, Sir Arthur Sullivan, wrote: "In all his works Clay showed a natural gift of graceful melody and a feeling for rich harmonic colouring. [His songs included] 'She wandered down the mountain side,' 'Long ago' and 'The Sands of Dee'".[3] Other songs that achieved popularity are "Gipsy John" and "Who Knows".[5][10]

After conducting the second performance of The Golden Ring in December 1883, Clay suffered a stroke that paralysed him and cut short his productive life.[1] In 1889 at the age of 51, he was found drowned in his bath at the home of his sisters in Great Marlow, England, presumably a suicide. He was buried in Brompton cemetery.[2]

Notes

- ^ a b "Death of Sir Frederic Clay", The Birmingham Daily Post, 29 November 1889, p. 5

- ^ a b c Knowles, Christopher. "Clay, Frederic Emes (1838–1889)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 10 October 2008

- ^ a b c d Sullivan, Arthur. "Frederic Clay (1838–1889)", Archived 30 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, reprinted at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

- ^ a b c "Death of Mr Frederic Clay", The Era, 30 November 1889, p. 9

- ^ a b c d Scowcroft, Philip L. A 101st Garland of British Light Music Composers, Classical Music Web, MusicWeb-International.com

- ^ Ainger, p. 87; Jacobs, p. 53. The Scott Russells forbade the relationship between Sullivan and Rachel, because Sullivan had uncertain financial prospects, although Rachel continued to see him covertly. At some point in 1868, Sullivan started a simultaneous (and secret) affair with the eldest daughter, Louise, but both relationships had ceased by early 1869.

- ^ Gänzl, p. 16, says: "Constance was written to a rather 'heavy' libretto. ... It was a tale of love and patriotism set in Poland under the Russians – something of a Polish Tosca, but with a happy ending when the hero and heroine are rescued first by a singing vivandiere and then by the Polish army. The music ... was noted as being promising if rather light and, after being performed eighteen times as a curtain-raiser to the Covent Garden pantomime of Cinderella, it sank into obscurity." The score is available at the National Library of Scotland.

- ^ Crowther, Andrew, Analysis of Ages Ago Archived 3 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive (2006)

- ^ The Era, 24 July 1870, p. 6

- ^ a b c Obituary, The Times, 29 November 1889, p. 5, col. F

- ^ Information about The Merry Duchess

- ^ Gänzl, p. 228

- ^ Gänzl, p. 230

- ^ Gänzl, pp. 228 and 230

References

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan – A Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514769-3.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 470.

- Davey, Henry (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Gänzl, Kurt. British musical theatre, Vol. 1: 1865–1914, New York: Oxford University Press (1986)

- Jacobs, Arthur (1984). Arthur Sullivan: A Victorian Musician. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315443-9.

- Searle, T. A bibliography of Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (1931)

- Sims, G. R. My life (1917)

- Stedman, Jane W. Gilbert before Sullivan, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul (1967)

- "Mr Frederick Clay", The Ray, 11 March 1880

- "Mr Frederick Clay at Clarence Chambers", The World, 18 March 1883

External links

- List of Clay works at The Guide to Light Opera & Operetta

- Free scores by Frederic Clay at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)