USS Randolph (1776)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Randolph |

| Namesake | Peyton Randolph |

| Ordered | 13 December 1775 |

| Builder | Wharton and Humphreys |

| Launched | 10 July 1776 |

| Fate | Sunk by explosion, 7 March 1778 (311 killed/4 survived) |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Frigate |

| Length | 132 ft 9 in (40.46 m) |

| Beam | 34 ft 6 in (10.52 m) |

| Draft | 18 ft (5.5 m) |

| Depth | 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m) |

| Complement | 315 |

| Armament | 26 x 12 pdrs; 10 x 6 pdrs |

| Service record | |

| Commanders: | Capt. Nicholas Biddle |

| Operations: | |

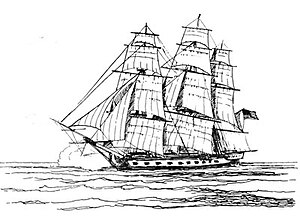

The first USS Randolph was a 32-gun frigate in the Continental Navy named for Peyton Randolph.

Construction

Construction of the first Randolph was authorized by the Continental Congress on 13 December 1775. The frigate, designed by Joshua Humphreys, was launched on 10 July 1776, by Wharton and Humphreys at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Captain Nicholas Biddle was appointed commander of the Randolph on 11 July, and he took charge of the frigate in mid-October.

Maiden Voyage

Seamen were scarce and recruiting was slow, delaying the ship's maiden voyage. Captured British seamen were "dragged" from jail in Philadelphia; the resulting riot required the soldiers appointed to carry the men to the ship to fire into the prison windows.[1] Finally manned, Randolph sailed down the Delaware River on 3 February 1777, and three days later rounded Cape Henlopen, escorting a large group of American merchantmen to sea. On the 15th, the convoy separated, with some of Randolph's charges heading for France and the rest setting course for the West Indies.

The frigate herself turned northward, hoping to encounter HMS Milford, a British frigate which had been capturing New England shipping. Before long, she boarded a ship which proved to be French and was set free. Then, as she continued the search, Randolph sprung her foremast. While the crew labored to rig a spar as a jury mast, the ship's mainmast broke and toppled into the sea.

Continuing the hunt was out of the question. Now seeking to avoid the Royal Navy's warships, Biddle ordered the ship south toward the Carolina coast.

Fever broke out as the Randolph painfully made her way, and many members of the crew were buried at sea. A mutiny of the captured British seamen had to be put down[1] before the ship could reach Charleston, South Carolina, on the afternoon of 11 March.

Voyage to Philadelphia

Twice, after her repairs had been completed and as she was about to get underway, the frigate was kept in port by lightning-splintered mainmasts. Meanwhile, the ship, undermanned when she left Philadelphia, was losing more of her men from sickness, death, and desertion.

Recruiting was stimulated by bounty, and Randolph was finally readied for sea - this time with her masts protected by lightning rods. She departed Charleston on 16 August and entered Rebellion Road to await favorable winds to put to sea. Two days later, a party from the frigate boarded merchantman Fair American, and impressed two seamen who earlier had been lured away from Biddle's ship.

Inshore winds kept Randolph in the roadstead until the breeze shifted on 1 September, wafting the frigate across Charleston Bar. At dusk, on the 3rd, a lookout spotted five vessels: two ships, two brigs, and a sloop. After a nightlong chase, she caught up with her quarry the next morning and took four prizes: a 20-gun privateer, True Briton, laden with rum, for the British troops at New York; Severn, the second prize, had been recaptured by True Briton from a North Carolina privateer while sailing from Jamaica to London with a cargo of sugar, rum, ginger, and logwood; the two brigs, Charming Peggy, a French privateer, and L’Assomption, laden with salt, had also been captured by True Briton while plying their way from Martinique to Charleston.

Randolph and her rich prizes reached Charleston on the morning of 6 September. While the frigate was in port having her hull scraped, the president of South Carolina's General Assembly, John Rutledge, suggested to Biddle that Randolph, aided by a number of State Navy ships, might be able to break the blockade which was then bottling up a goodly number of American merchantmen in Charleston Harbor. Biddle accepted command of the task force, which, besides Randolph, included General Moultrie, Notre Dame, Fair American, and Polly.

The American ships sailed on 14 February 1778. When they crossed the bar, Biddle's ships found no British cruisers. After seeing a number of merchantmen to a good offing, the ships proceeded to the West Indies hoping to intercept British merchantmen. After two days, they took and burned a dismasted New England ship which had been captured by a British privateer while headed for St. Augustine, Florida. Thereafter, game was scarce. They encountered only neutral ships until Polly took a small schooner on 4 March bound from New York to Grenada. Biddle manned the prize as a tender.

Loss

On the afternoon of 7 March, Randolph's lookouts spotted sail on the horizon. At 21:00 that evening, that ship, now flying British colors, came up on the Randolph as the largest ship in the convoy, and demanded they hoist their colors. The Randolph then hoisted American colors and fired a broadside into the British ship, mistakenly believing the ship to be a large sloop.[1] The stranger turned out to be the British 64-gun ship of the line, HMS Yarmouth.

As a 64-gun, two-deck line-of-battle ship, Yarmouth had double the number of guns as Randolph. Yarmouth's guns were also significantly heavier, mounting 32 pound cannons on her main deck, 18 pounder guns on her upper deck and 9 pounder guns on her quarterdeck and forecastle, giving her almost five times the weight of shot that Randolph could fire. The Randolph and General Moultrie engaged Yarmouth until the Randolph's magazine exploded with a blinding flash. The Yarmouth was struck with burning debris up to six feet long, which significantly damaged her sails and rigging as well as killing five, and wounding twelve.[1][2]

The damage caused to Yarmouth's sails and rigging prevented her from pursuing the remaining South Carolina ships which slipped away in the darkness.[2]

The loss of the Randolph resulted in the deaths of 311 of her crew, including Capt. Nicholas Biddle,[3] with 4 survivors.[4][5]

References

- ^ a b c d James, William (1817). A Full and Correct Account of the Chief Naval Occurrences of the Late War Between Great Britain and the United States of America. T. Egerton. pp. 40–44.

- ^ a b "Copy of a Letter from Captain Vincent, of His Majesty's Ship Yarmouth, to Admiral Yong". The London Gazette. 19 May 1778. p. 2.

- ^ Allen, Gardner Weld (1913). A naval history of the American Revolution. Vol. 1. Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 296–298.

- ^ Maclay, Edgar Stanton (1898). A History of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1898. D. Appleton and Co. pp. 83–84.

- ^ "Action off Barbados". James F. Justin Museum. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

![]() This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.