El Llano en llamas

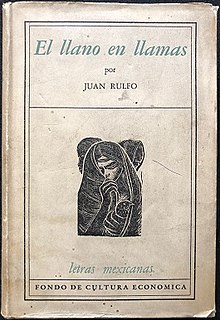

First edition | |

| Author | Juan Rulfo |

|---|---|

| Original title | El Llano en Llamas (Spanish) |

| Translator | into English: George D. Schade; Ilan Stavans; Stephen Beechinor into French: Gabriel Iaculli |

| Language | Spanish translated into French and into English |

| Genre | Short story collection |

| Publisher | Fondo de Cultura Económica |

Publication date | 1953 |

| Publication place | Mexico |

| Pages | 170 pp |

| ISBN | 978-0-292-70132-8 |

| OCLC | 20956761 |

El llano en llamas (translated into English as The Burning Plain and Other Stories,[1] The Plain in Flames,[2] and El Llano in flames[3]) is a collection of short stories written in Spanish by Mexican author Juan Rulfo and first published in 1953.

Literary reputation of the author

This collection and a novel entitled Pedro Páramo published within three years of each other in the 1950s established Rulfo's literary reputation.[4] One review of these stories praises these seventeen tales of rural folk because they "prove Juan Rulfo to be one of the master storytellers of modern Mexico....". The reviewer also noted that Rulfo

- has an eye for the depths of the human soul,

- an ear for the 'still sad music of humanity,'

- and a gift for communicating what takes place internally and externally in man.

Range of writing styles in these stories

- brief anecdotes

- casual incidents that remind one of 'happenings' in pop art

- short stories. (According to one reviewer, many of these stories are written in deceptively elemental language and narrative technique.)[5]

In his introduction to the Texas edition, translator George D. Schade describes some of the stories as long sustained interior monologues ("Macario", "We're very poor", "Talpa", "Remember"), while in other stories that may have otherwise been essentially monologues dialogues are inserted ("Luvina", "They have Given Us the Land" and ""Anacleto Morones"). A few stories, according to Schade, are scarcely more than anecdotes like "The Night They Left Him Alone".

Geographical background

The short stories in El llano en llamas are set in the harsh countryside of the Jalisco region where Rulfo was raised. They explore the tragic lives of the area's inhabitants, who suffer from extreme poverty, family discord, and crime.[4] With a few bare phrases the author conveys a feeling for the bleak, harsh surroundings in which his people live.[5]

Mentioned in the Nobel Lecture, 2008

The French writer J.M.G. Le Clézio, who was the 2008 Nobel literature laureate, mentioned in his Nobel Lecture not only the writer Juan Rulfo, but also the short stories from El llano en llamas and the novel Pedro Páramo.[6]

Stories

| # | Original Spanish | English translation | Pages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Macario | Macario | |

| 2 | Nos han dado la tierra | They gave us the land | |

| 3 | La cuesta de las comadres | The Hill of the Mothers-in-law | |

| 4 | Es que somos muy pobres | We're just very poor | |

| 5 | El hombre | The man | |

| 6 | En la madrugada | At daybreak | |

| 7 | Talpa | Talpa | |

| 8 | El llano en llamas | The burning Plain | |

| 9 | ¡Diles que no me maten! | Tell them not to kill me! | |

| 10 | Luvina | Luvina | |

| 11 | La noche que lo dejaron solo | The night they left him alone | |

| 12 | Acuérdate | Remember | |

| 13 | ¿No oyes ladrar los perros? | Can't you hear the dogs barking? | |

| 14 | Paso del Norte | North Pass | |

| 15 | Anacleto Morones | Anacleto Morones | |

| 16 | La herencia de Matilde Arcángel | The Legacy of Matilde Arcángel | |

| 17 | El día del derrumbe | The Day of the Collapse |

Macario

Written like a monologue, where an orphaned town idiot named Macario describes in his flowing narrative a few of the special aspects of his everyday life.[7] In "Macario", the past and present mingle chaotically, and frequently the most startling associations of ideas are juxtaposed, strung together by conjunctions which help to paralyze the action and stop the flow of time in the present. Rulfo succeeds in this excellent story in capturing the sickly atmosphere surrounding the idiot boy, who is gnawed by hunger and filled with the terror of hell, and protected, and at the same time exploited, by his Godmother and the servant girl Felipa.[8]

Nos han dado la tierra (They gave us the land)

"The story begins with the narrator hearing the sound of dogs barking after walking for hours without coming across a trace of anything living on the plain".[9] They gave us the land depicts the results of the government's land reform program for four poor countrymen who have been given a parcel of land. They march across a barren plain to reach their property, which is located too far from any source of water to be of any use to them.

La cuesta de las comadres (The Hill of the Mothers-in-law)

"The narrator begins by talking about the Torricos, the controlling family of the Hill of the Comadres who, despite being good friends of his, are the enemies of the other residents of the hill and of those who live in nearby Zapotlán".[10]

Es que somos muy pobres (We’re just very poor)

According to Gradesaver Study Guides "“We’re very poor” begins with a sentence that sums up the tone of the story quite well: “Everything is going from bad to worse here.” The narrator is speaking about the hardships that his family has recently had to endure, and he subsequently tells us that his Aunt Jacinta died last week, and then during the burial “it began raining like never before”.[11] Es que somos muy pobres in Spanish online[12]

El hombre (The man)

"The first of this very challenging story’s two parts is narrated in third person and alternates between descriptions of two different people: a fugitive “man” and his “pursuer,” often referred to as “the one who was following him"[13] .[14] El hombre in Spanish online[15]

En la madrugada (At daybreak)

"The third person narrator begins with a separated eerie description of the town of San Gabriel. The town “emerges from the fog laden with dew,” and the narrator describes a number of elements that serve to obscure it from view: clouds, rising steam and black smoke from the kitchens"[16]

Talpa

“Talpa” is narrated in third person by a nameless character who is described only as the brother of Tanilo and the lover of Tanilo’s wife, Natalia. The story begins at what is technically its end, with a description of Natalia throwing herself into her mother’s arms and sobbing upon their return to Zenzontla. The narrator recounts how Tanilo was ill and covered in painful blisters. Natalia and the narrator planned to bring Tanilo to Talpa, ostensibly so that he could be cured by the Virgin of Talpa, but in reality because they hoped he would die so they could continue their extramarital relationship without guilt. After Tanilo's death, however, Natalia refuses to speak to the narrator out of shame. The narrator concludes that he and Natalia must live with remorse and the memory of Tanilo's death as he watches Natalia cry with her mother. [17]

El llano en llamas (The burning plain)

"This story begins with an epigraph from a popular ballad. These words (“They’ve gone and killed the bitch / but the puppies still remain…”) refer to the way that the spark that began the Revolution created successive movements which were often quite independent of its original impulses and were difficult to bring to heel."[18]

¡Diles que no me maten! (Tell Them Not to Kill Me!)

"In “Tell Them Not to Kill Me!” Juvencio Nava pleads with his son Justino to intervene on his behalf in order to stop his execution by firing squad. Juvencio is about to be executed by a colonel for the murder of a man, Don Lupe, forty years earlier. The conflict arose when Don Lupe would not allow Juvencio to let his livestock graze on his land, and Juvencio did it anyway."[19] Tell Them Not to Kill Me! is about an old man, set to be executed, whose prison guard happens to be the son of a man he killed. Published as the seventh story in 1951 with a preface by Elias Canetti and Günter Grass [4] ¡Diles que no me maten! with Juan Rulfo Voice[20]

Luvina

"Like other stories in The Burning Plain, “Luvina” is written in the form of a confession or story told by one man to another. In this case the speaker is the teacher who previously taught in the town of Luvina, speaking to the new teacher who is about to travel there. The reader does not discover this until midway through the story, however."[21]

La noche que lo dejaron solo (The night they left him alone)

According to Gradesaver Study Guides "This story takes place between 1926 and 1929 during what was known as the Cristero War. It is told in third person by an omniscient narrator who describes the flight of a Cristero soldier, Feliciano Ruelas, from a successful ambush of federal troops."[22] tells the story of a man pursued by federal troops who kill his family members when they cannot locate him. La noche que lo dejaron solo in Spanish online[23]

Acuérdate (Remember)

"The narrator tells us that Urbano Gómez died a while ago, perhaps fifteen years, but that he was a memorable person. He was often called “Grandfather” and his other son, Fidencio, had two “frisky” daughters, one of which had the mean nickname of “Stuck Up.” The other daughter was tall and blue-eyed and many said she wasn’t his."[24] Acuérdate in Spanish[25]

¿No oyes ladrar los perros? (Don't you hear the dogs barking?)

Inappropriately titled as translated by Georg D. Schade (in The Burning Plain and Other Stories), since the Spanish refers to a father's anger with his son for not having helped him hear the dogs, which were, indeed, barking."[26] The story opens with a father’s request that his son Ignacio tell him if he can’t hear anything or see any lights in the distance: “You up there, Ignacio! Don’t you hear something or see a light somewhere?” Ignacio responds that he does not, and the father says that they must be getting close"[27] about a man carrying his estranged, adult, wounded son on his back to find a doctor. There is a translation of "¿No oyes ladrar los perros?" in English with the title " No dogs bark" at the University of Texas web-site.[8]

Paso del Norte (North Pass)

The father asks the son where he is headed and learns his destination is “up North.” The son’s pig-buying business has failed and his family is starving, in contrast with his father. The son says the father can not understand his family’s suffering because he sells “skyrockets and firecrackers and gun powder” which are popular whenever there are holiday celebrations. The business in pigs is more seasonal and therefore less successful."[28]

Anacleto Morones

This is one of the longer stories in "The Burning Plain".It is told in first person by the character of Lucas Lucatero. Lucatero begins the story by cursing the women who have come to visit him saying:

“Old women, daughters of the devil!

I saw them coming all together in a procession.

Dressed in black, sweating like mules under the hot sun.".[29]

"Anacleto Morones" is a story of pride and jealousy. The narrator, Lucas Lucatero, does not confess to the crime directly, but the repeated references to the pile of stones serves to notify the reader of the place of rest of the body of Lucatero's father-in-law Anacleto Morones[30]

La herencia de Matilde Arcángel (The Legacy of Matilde Arcángel)

This is one of two short stories that the author added to the second edition of the Spanish language collection in 1970. The final version of the collection has seventeen short stories.[31] La herencia de Matilde Arcángel in Spanish online[32]

El día del derrumbe (The Day of the Collapse)

This is one of two short stories that the author added to the second edition of the Spanish language collection in 1970. The final version of the collection has seventeen short stories.[31]

References

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories". University of Texas Press. 2019. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

Juan Rulfo received international acclaim for his brilliant short novel Pedro Páramo (1955) and his collection of short stories El llano en llamas (1953), translated as a collection here in English for the first time.

- ^ "The Plain in Flames". University of Texas Press. 2019. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

Working from the definitive Spanish edition of El llano en llamas established by the Fundación Juan Rulfo, Ilan Stavans and co-translator Harold Augenbram present fresh translations of the original fifteen stories, as well as two more stories that have not appeared in English before—"The Legacy of Matilde Arcángel" and "The Day of the Collapse."

- ^ "Structo Press | Structo". Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- ^ a b "Short Story Criticism Rulfo, Juan 1918–1986". Critical Reception. eNotes.com. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Editorial Reviews". Saturday Review and Houston Post. Amazon.comAmazon. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ "Le Clézio Nobel Lecture". Le Clézio "In the forest of paradoxes". THE NOBEL FOUNDATION. 2008-12-07. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

(translation) To Juan Rulfo, to Pedro Paramo, and to the short stories from El llano en llamas, to the simple and tragic photographs that he took in the Mexican countryside

(original French) À Juan Rulfo, à Pedro Paramo et aux nouvelles du El llano en llamas, aux photos simples et tragiques qu'il a faites dans la campagne mexicaine - ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Introduction". George D. Schade. University of Texas Press. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "Juan Rulfo / El llano en llamas / Es que somos muy pobres" (Online Text) (in Spanish). la Página de Los Cuentos. 2002-01-26. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "Juan Rulfo / El llano en llamas / El hombre" (Online Text) (in Spanish). la Página de Los Cuentos. 2002-01-26. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ Sound recording of reading "¡Diles que no me maten!". Sound recording of reading. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "Juan Rulfo / El llano en llamas / La noche que lo dejaron solo" (Online Text) (in Spanish). la Página de Los Cuentos. 2002-01-26. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "Juan Rulfo / El llano en llamas / Acuérdate" (Online Text) (in Spanish). la Página de Los Cuentos. 2002-01-26. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Classe, Olive (2000). Encyclopedia of literary translation into English. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 1201. ISBN 978-1-884964-36-7.

"No dogs bark" is inappropriately titled, since the Spanish, "No oyes ladrar los perros", or "You don't hear dogs barking", refers to a father's anger

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ "The Burning Plain and Other Stories Study Guide". Short Summary According to Gradesaver Study Guides. 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ Echevarría, Roberto González; Enrique Pupo-Walker (1996). The Cambridge History of Latin American Literature: The twentieth century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 471–472, 639. ISBN 9780521340700.

- ^ a b A partir de 1970, fecha de la segunda edición, revisada por el autor, se incluyen dos cuentos más; El día del derrumbe y La herencia de Matilde Arcángel, haciendo un total de diecisiete relatos que conforman la versión definitiva.

- ^ "Juan Rulfo / El llano en llamas / La herencia de Matilde Arcángel" (Online Text) (in Spanish). la Página de Los Cuentos. 2002-01-26. Retrieved 6 January 2009.