The Kreutzer Sonata

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2018) |

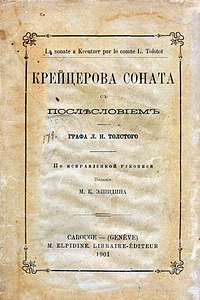

Title page of the 1901 Geneve edition in Russian | |

| Author | Leo Tolstoy |

|---|---|

| Original title | Крейцерова соната, Kreitzerova Sonata |

| Translator | Frederic Lyster (1890) David McDuff & Paul Foote (2008) |

| Language | Russian, French, English, German |

| Genre | Philosophical fiction |

| Publisher | Bibliographic Office, Berlin |

Publication date | 1889 |

| Publication place | Russia |

| Pages | 118 (Pollard's 1890 English edition) |

| ISBN | 978-0-14-044960-0 |

| Text | The Kreutzer Sonata at Wikisource |

The Kreutzer Sonata (Template:Lang-ru, Kreitzerova Sonata) is a novella by Leo Tolstoy, named after Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata. The novella was published in 1889, and was promptly censored by the Russian authorities. The work is an argument for the ideal of sexual abstinence and an in-depth first-person description of jealous rage. The main character, Pozdnyshev, relates the events leading up to his killing of his wife: in his analysis, the root causes for the deed were the "animal excesses" and "swinish connection" governing the relation between the sexes.

Summary

During a train ride, Pozdnyshev overhears a conversation concerning marriage, divorce and love. When a woman argues that marriage should not be arranged but based on true love, he asks "what is love?" and points out that, if understood as an exclusive preference for one person, it often passes quickly. Convention dictates that two married people stay together, and initial love can quickly turn into hatred. He then relates how he used to visit prostitutes when he was young, and complains that women's dresses are designed to arouse men's desires. He further states that women will never enjoy equal rights to men as long as men view them as objects of desire, yet describes their situation as a form of power over men, mentioning how much of society is geared towards their pleasure and well-being and how much sway they have over men's actions.

After he meets and marries his wife, periods of passionate love and vicious fights alternate. She bears five children, and then receives contraceptives: "The last excuse for our swinish life – children – was then taken away, and life became viler than ever." His wife takes a liking to a violinist, Troukhatchevsky, and the two perform Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata (Sonata No. 9 in A Major for piano and violin, Op. 47) together. Pozdnyshev complains that some music is powerful enough to change one's internal state to a foreign one. He hides his raging jealousy and goes on a trip, returns early, finds Troukhatchevsky and his wife together and kills his wife with a dagger. The violinist escapes: "I wanted to run after him, but remembered that it is ridiculous to run after one's wife's lover in one's socks; and I did not wish to be ridiculous but terrible."

Later acquitted of murder in light of his wife's apparent adultery, Pozdnyshev rides the train and tells his story to a fellow passenger, the narrator.

Censorship

After the work had been forbidden in Russia by the censors, a mimeographed version was widely circulated. In 1890, the United States Post Office Department prohibited the mailing of newspapers containing serialized installments of The Kreutzer Sonata. This was confirmed by the U.S. Attorney General in the same year. Theodore Roosevelt called Tolstoy a "sexual moral pervert."[1] The ban on its sale was struck down in New York and Pennsylvania courts in 1890.[2][3]

Epilogue

In the Epilogue To The Kreutzer Sonata, published in 1890, Tolstoy clarifies the intended message of the novella, writing:

Let us stop believing that carnal love is high and noble and understand that any end worth our pursuit – in service of humanity, our homeland, science, art, let alone God – any end, so long as we may count it worth our pursuit, is not attained by joining ourselves to the objects of our carnal love in marriage or outside it; that, in fact, infatuation and conjunction with the object of our carnal love (whatever the authors of romances and love poems claim to the contrary) will never help our worthwhile pursuits but only hinder them.[citation needed]

Countering the argument that widespread abstinence would lead to a cessation of the human race, he describes chastity as an ideal that provides guidance and direction, not as a firm rule. Writing from a position of deep religiosity (that he had explained in his Confession in 1882), he points out that not Christ, but the Church (which he despises) instituted marriage. "The Christian's ideal is love of God and his neighbor, self-renunciation in order to serve God and his neighbour; carnal love, marriage, means serving oneself, and therefore is, in any case, a hindrance in the service of God and men".[citation needed]

During the international celebration of Tolstoy's 80th birthday in 1908, G. K. Chesterton criticized this aspect of Tolstoy's thought in an article in the 19 September issue of Illustrated London News: "Tolstoy is not content with pitying humanity for its pains: such as poverty and prisons. He also pities humanity for its pleasures, such as music and patriotism. He weeps at the thought of hatred; but in The Kreutzer Sonata he weeps almost as much at the thought of love. He and all the humanitarians pity the joys of men." He went on to address Tolstoy directly: "What you dislike is being a man. You are at least next door to hating humanity, for you pity humanity because it is human."[citation needed]

Adaptations

Plays

- The novella was adapted into a Yiddish play in 1902 by Russian-Jewish playwright Jacob Gordin. American playwright Langdon Mitchell later adapted Gordin's version into English, which debuted on Broadway on September 10, 1906.[citation needed]

- In 2007 in Wellington, New Zealand, a newly devised theatrical work, The Kreutzer, was premiered, combining dance, music, theatre and multimedia projections with both pieces of music (Beethoven and Janáček) played live. Sara Brodie provided the adaptation, direction and choreography. A reworked version was presented in Auckland during March 2009 at The Auckland Festival.

- The novella was adapted for the stage by Darko Spasov in 2008, and produced as a one-act play in 2009 for the National Theatre in Štip, Republic of Macedonia, directed by Ljupco Bresliski, performed by Milorad Angelov.[4]

- Laura Wade's Kreutzer vs. Kreutzer is also inspired by Tolstoy.[5]

- The novella was adapted for the stage by Ted Dykstra and produced as a one-act play for the Art of Time Ensemble of Toronto in 2008, and again for the Soulpepper Theatre Company in 2011.

- Nancy Harris adapted the novella into a one-act monologue for the Gate Theatre in London in 2009, directed by Natalie Abrahami and starring Hilton McRae. The production was revived in 2012 at the Gate Theatre, and also at La MaMa in New York City.

- The novella was adapted by Sue Smith for the State Theatre Company of South Australia as part of the 2013 Adelaide Festival. It was directed by Geordie Brookman and featured Renato Musolino (who stepped into the role at the last minute, as a replacement for Barry Otto, who had taken ill).[6]

- A one-act adaptation[7] by Utah playwright Eric Samuelson was produced by Plan-B Theatre Company and the NOVA Chamber Music Series in 2015. It ran from 18 October to 9 November at the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center in Salt Lake City, Utah. It was directed by Jerry Rapier, and featured Robert Scott Smith, Kathryn Eberle, and Jason Hardnik. Eberle and Hardnik were musicians in the Utah Symphony at the time.[8]

Films

The Kreutzer Sonata has been adapted for film well over a dozen times. Some of these include:[citation needed]

- The Kreutzer Sonata (1911, Russian Empire), directed by Pyotr Chardynin

- The Kreutzer Sonata (1914, Russian Empire), directed by Vladimir Gardin

- The Kreutzer Sonata (1915, USA), directed by Herbert Brenon

- Kreutzerova sonáta (1927, Czechoslovakia), directed by Gustav Machatý

- Kreutzersonate (1937, Germany), directed by Veit Harlan

- Prelude to Madness (1948, Italy), directed by Gianni Franciolini

- La Sonate à Kreutzer (1956, France), short film directed by Éric Rohmer[9]

- Kreitserova sonata (1969, TV, Yugoslavia) directed by Jovan Konjović

- The Kreutzer Sonata (1987, USSR), directed by Mikhail Shveytser

- Quale amore (2006, Italy), directed by Maurizio Sciarra

- The Kreutzer Sonata (2008, UK), directed by Bernard Rose and starring Elisabeth Röhm

- Sonata (2013, Spain), directed by Jon Ander Tomás

Music

The novella, inspired by Beethoven's music, in turn gave rise to Leoš Janáček's First String Quartet.[10]

Ballet

In 2000, the Carolina Ballet, with original choreography by Robert Weiss and combining the music of Beethoven, Janáček, and J. Mark Scearce, mounted an innovative production combining dance and drama, with a narrator/actor telling the story and flashbacks leading into the ballet segments.[11]

Painting

The novella inspired the 1901 painting Kreutzer Sonata by René François Xavier Prinet, which shows a passionate kiss between the violinist and the pianist. The painting was used for years in Tabu perfume ads.[citation needed]

Novels

Arab Israeli author Sayed Kashua's 2010 novel Second Person Singular echoes The Kreutzer Sonata set in present-day Israel. A copy of The Kreutzer Sonata also functions as a major plot device.[12]

The Dutch author Margriet de Moor wrote a book called Kreutzersonate after Janáček's string quartet, which was inspired by the novella and Beethoven.

See also

References

- ^ The Everything Theodore Roosevelt Book: The extraordinary life of an American icon, Arthur G Sharp, MA

- ^ "Count Tolstoi Not Obscene", The New York Times, September 25, 1890

- ^ "'Kreutzer Sonata' in Court", The New York Times, August 8, 1890

- ^ www.culture.in.mk Archived 2013-02-21 at archive.today

- ^ "What's On". Sydney Opera House.

- ^ Walsh, Liz (31 May 2013). "The one-man show must go on". The Advertiser. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ The playwright described his work as "a conduit to the story" rather than a full adaptation.

- ^ "The Salt Lake Tribune, 18 October 2015, p. D1".

- ^ "The Kreutzer Sonata" – via mubi.com.

- ^ Katya Kabanova (Prague National Theatre, Jaroslav Krombholc) (CD). Leoš Janáček. Prague: Supraphon. p. 6. 108016-2612.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Carolina Ballet takes on Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Chris Baysden, Triangle Business Journal, 23 February 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2018. (subscription required)

- ^ "Hebrew Fiction / An Escape Route". Haaretz.

External links

Complete Work Online

- Complete Text in English

- "The Kreutzer Sonata", from RevoltLib

- "The Kreutzer Sonata", from Marxists.org

- Complete Audio in English

The Kreutzer Sonata public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Kreutzer Sonata public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Complete Text in Russian

- Full text of The Kreutzer Sonata in the original Russian, from Ilibrary.ru