Conceptual model

A conceptual model is a representation of a system. It consists of concepts used to help people know, understand, or simulate a subject the model represents. In contrast, physical models are physical objects, such as a toy model that may be assembled and made to work like the object it represents.

The term may refer to models that are formed after a conceptualization or generalization process.[1][2] Conceptual models are often abstractions of things in the real world, whether physical or social. Semantic studies are relevant to various stages of concept formation. Semantics is basically about concepts, the meaning that thinking beings give to various elements of their experience.

Overview

Models of concepts and models that are conceptual

The term conceptual model is normal. It could mean "a model of concept" or it could mean "a model that is conceptual." A distinction can be made between what models are and what models are made of. With the exception of iconic models, such as a scale model of Winchester Cathedral, most models are concepts. But they are, mostly, intended to be models of real world states of affairs. The value of a model is usually directly proportional to how well it corresponds to a past, present, future, actual or potential state of affairs. A model of a concept is quite different because in order to be a good model it need not have this real world correspondence.[3] In artificial intelligence, conceptual models and conceptual graphs are used for building expert systems and knowledge-based systems; here the analysts are concerned to represent expert opinion on what is true not their own ideas on what is true.

Type and scope of conceptual models

Conceptual models (models that are conceptual) range in type from the more concrete, such as the mental image of a familiar physical object, to the formal generality and abstractness of mathematical models which do not appear to the mind as an image. Conceptual models also range in terms of the scope of the subject matter that they are taken to represent. A model may, for instance, represent a single thing (e.g. the Statue of Liberty), whole classes of things (e.g. the electron), and even very vast domains of subject matter such as the physical universe. The variety and scope of conceptual models is due to the variety of purposes had by the people using them.

Conceptual modeling is the activity of formally describing some aspects of the physical and social world around us for the purposes of understanding and communication."[4]

Fundamental objectives

A conceptual model's primary objective is to convey the fundamental principles and basic functionality of the system which it represents. Also, a conceptual model must be developed in such a way as to provide an easily understood system interpretation for the model's users. A conceptual model, when implemented properly, should satisfy four fundamental objectives.[5]

- Enhance an individual's understanding of the representative system

- Facilitate efficient conveyance of system details between stakeholders

- Provide a point of reference for system designers to extract system specifications

- Document the system for future reference and provide a means for collaboration

The conceptual model plays an important role in the overall system development life cycle. Figure 1[6] below, depicts the role of the conceptual model in a typical system development scheme. It is clear that if the conceptual model is not fully developed, the execution of fundamental system properties may not be implemented properly, giving way to future problems or system shortfalls. These failures do occur in the industry and have been linked to; lack of user input, incomplete or unclear requirements, and changing requirements. Those weak links in the system design and development process can be traced to improper execution of the fundamental objectives of conceptual modeling. The importance of conceptual modeling is evident when such systemic failures are mitigated by thorough system development and adherence to proven development objectives/techniques.

Modelling techniques

As systems have become increasingly complex, the role of conceptual modelling has dramatically expanded. With that expanded presence, the effectiveness of conceptual modeling at capturing the fundamentals of a system is being realized. Building on that realization, numerous conceptual modeling techniques have been created. These techniques can be applied across multiple disciplines to increase the user's understanding of the system to be modeled.[7] A few techniques are briefly described in the following text, however, many more exist or are being developed. Some commonly used conceptual modeling techniques and methods include: workflow modeling, workforce modeling, rapid application development, object-role modeling, and the Unified Modeling Language (UML).

Data flow modeling

Data flow modeling (DFM) is a basic conceptual modeling technique that graphically represents elements of a system. DFM is a fairly simple technique, however, like many conceptual modeling techniques, it is possible to construct higher and lower level representative diagrams. The data flow diagram usually does not convey complex system details such as parallel development considerations or timing information, but rather works to bring the major system functions into context. Data flow modeling is a central technique used in systems development that utilizes the structured systems analysis and design method (SSADM).

Entity relationship modeling

Entity–relationship modeling (ERM) is a conceptual modeling technique used primarily for software system representation. Entity-relationship diagrams, which are a product of executing the ERM technique, are normally used to represent database models and information systems. The main components of the diagram are the entities and relationships. The entities can represent independent functions, objects, or events. The relationships are responsible for relating the entities to one another. To form a system process, the relationships are combined with the entities and any attributes needed to further describe the process. Multiple diagramming conventions exist for this technique; IDEF1X, Bachman, and EXPRESS, to name a few. These conventions are just different ways of viewing and organizing the data to represent different system aspects.

Event-driven process chain

The event-driven process chain (EPC) is a conceptual modeling technique which is mainly used to systematically improve business process flows. Like most conceptual modeling techniques, the event driven process chain consists of entities/elements and functions that allow relationships to be developed and processed. More specifically, the EPC is made up of events which define what state a process is in or the rules by which it operates. In order to progress through events, a function/ active event must be executed. Depending on the process flow, the function has the ability to transform event states or link to other event driven process chains. Other elements exist within an EPC, all of which work together to define how and by what rules the system operates. The EPC technique can be applied to business practices such as resource planning, process improvement, and logistics.

Joint application development

The dynamic systems development method uses a specific process called JEFFF to conceptually model a systems life cycle. JEFFF is intended to focus more on the higher level development planning that precedes a project's initialization. The JAD process calls for a series of workshops in which the participants work to identify, define, and generally map a successful project from conception to completion. This method has been found to not work well for large scale applications, however smaller applications usually report some net gain in efficiency.[8]

Place/transition net

Also known as Petri nets, this conceptual modeling technique allows a system to be constructed with elements that can be described by direct mathematical means. The petri net, because of its nondeterministic execution properties and well defined mathematical theory, is a useful technique for modeling concurrent system behavior, i.e. simultaneous process executions.

State transition modeling

State transition modeling makes use of state transition diagrams to describe system behavior. These state transition diagrams use distinct states to define system behavior and changes. Most current modeling tools contain some kind of ability to represent state transition modeling. The use of state transition models can be most easily recognized as logic state diagrams and directed graphs for finite-state machines.

Technique evaluation and selection

Because the conceptual modeling method can sometimes be purposefully vague to account for a broad area of use, the actual application of concept modeling can become difficult. To alleviate this issue, and shed some light on what to consider when selecting an appropriate conceptual modeling technique, the framework proposed by Gemino and Wand will be discussed in the following text. However, before evaluating the effectiveness of a conceptual modeling technique for a particular application, an important concept must be understood; Comparing conceptual models by way of specifically focusing on their graphical or top level representations is shortsighted. Gemino and Wand make a good point when arguing that the emphasis should be placed on a conceptual modeling language when choosing an appropriate technique. In general, a conceptual model is developed using some form of conceptual modeling technique. That technique will utilize a conceptual modeling language that determines the rules for how the model is arrived at. Understanding the capabilities of the specific language used is inherent to properly evaluating a conceptual modeling technique, as the language reflects the techniques descriptive ability. Also, the conceptual modeling language will directly influence the depth at which the system is capable of being represented, whether it be complex or simple.[9]

Considering affecting factors

Building on some of their earlier work,[10] Gemino and Wand acknowledge some main points to consider when studying the affecting factors: the content that the conceptual model must represent, the method in which the model will be presented, the characteristics of the model's users, and the conceptual model languages specific task.[9] The conceptual model's content should be considered in order to select a technique that would allow relevant information to be presented. The presentation method for selection purposes would focus on the technique's ability to represent the model at the intended level of depth and detail. The characteristics of the model's users or participants is an important aspect to consider. A participant's background and experience should coincide with the conceptual model's complexity, else misrepresentation of the system or misunderstanding of key system concepts could lead to problems in that system's realization. The conceptual model language task will further allow an appropriate technique to be chosen. The difference between creating a system conceptual model to convey system functionality and creating a system conceptual model to interpret that functionality could involve two completely different types of conceptual modeling languages.

Considering affected variables

Gemino and Wand go on to expand the affected variable content of their proposed framework by considering the focus of observation and the criterion for comparison.[9] The focus of observation considers whether the conceptual modeling technique will create a "new product", or whether the technique will only bring about a more intimate understanding of the system being modeled. The criterion for comparison would weigh the ability of the conceptual modeling technique to be efficient or effective. A conceptual modeling technique that allows for development of a system model which takes all system variables into account at a high level may make the process of understanding the system functionality more efficient, but the technique lacks the necessary information to explain the internal processes, rendering the model less effective.

When deciding which conceptual technique to use, the recommendations of Gemino and Wand can be applied in order to properly evaluate the scope of the conceptual model in question. Understanding the conceptual models scope will lead to a more informed selection of a technique that properly addresses that particular model. In summary, when deciding between modeling techniques, answering the following questions would allow one to address some important conceptual modeling considerations.

- What content will the conceptual model represent?

- How will the conceptual model be presented?

- Who will be using or participating in the conceptual model?

- How will the conceptual model describe the system?

- What is the conceptual models focus of observation?

- Will the conceptual model be efficient or effective in describing the system?

Another function of the simulation conceptual model is to provide a rational and factual basis for assessment of simulation application appropriateness.

General model theory

A model is a simplifying image of reality. The image can be either a sensorily, above all optically observable artefact or given purely theoretically. According to Herbert Stachowiak, a model is characterized by at least three properties:[11]

- 1. Mapping

- A model always is a model of something—it is an image or representation of some natural or artificial, existing or imagined original, where this original itself could be a model.

- 2. Reduction

- In general, a model will not include all attributes that describe the original but only those that appear as relevant to the model's creator or user.

- 3. Pragmatism

- A model does not relate unambiguously to its original. It is intended to work as a replacement for the original

- a) for certain subjects (for whom?)

- b) within a certain time range (when?)

- c) restricted to certain conceptual or physical actions (what for?).

For example, a street map is a model of the actual streets in a city (mapping), showing the course of the streets while leaving out, say, traffic signs and road markings (reduction), made for pedestrians and vehicle drivers for the purpose of finding one's way in the city (pragmatism).

Additional properties have been proposed, like extension and distortion[12] as well as validity.[13] The American philosopher Michael Weisberg differentiates between concrete and mathematical models and proposes computer simulations (computational models) as their own class of models.[14]

Models in philosophy and science

Mental model

In cognitive psychology and philosophy of mind, a mental model is a representation of something in the mind,[15] but a mental model may also refer to a nonphysical external model of the mind itself.[16]

Metaphysical models

A metaphysical model is a type of conceptual model which is distinguished from other conceptual models by its proposed scope; a metaphysical model intends to represent reality in the broadest possible way.[17] This is to say that it explains the answers to fundamental questions such as whether matter and mind are one or two substances; or whether or not humans have free will.

Conceptual model vs. semantics model

This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, the poor English might have a lot to do with it, but it is very hard to define even the basic idea of what the difference is between conceptual and semantic modelling. An example might help. (October 2014) |

Conceptual Models and semantic models have many similarities, however the way they are presented, the level of flexibility and the use are different. Conceptual models have a certain purpose in mind, hence the core semantic concepts are predefined in a so-called meta model. This enables a pragmatic modelling but reduces the flexibility, as only the predefined semantic concepts can be used. Samples are flow charts for process behaviour or organisational structure for tree behaviour.

Semantic models are more flexible and open, and therefore more difficult to model. Potentially any semantic concept can be defined, hence the modelling support is very generic. Samples are terminologies, taxonomies or ontologies.

In a concept model each concept has a unique and distinguishable graphical representation, whereas semantic concepts are by default the same. In a concept model each concept has predefined properties that can be populated, whereas semantic concepts are related to concepts that are interpreted as properties. In a concept model operational semantic can be built-in, like the processing of a sequence, whereas a semantic model needs explicit semantic definition of the sequence.

The decision if a concept model or a semantic model is used, depends therefore on the "object under survey", the intended goal, the necessary flexibility as well as how the model is interpreted. In case of human-interpretation there may be a focus on graphical concept models, in case of machine interpretation there may be the focus on semantic models.

Epistemological models

An epistemological model is a type of conceptual model whose proposed scope is the known and the knowable, and the believed and the believable.

Logical models

In logic, a model is a type of interpretation under which a particular statement is true. Logical models can be broadly divided into ones which only attempt to represent concepts, such as mathematical models; and ones which attempt to represent physical objects, and factual relationships, among which are scientific models.

Model theory is the study of (classes of) mathematical structures such as groups, fields, graphs, or even universes of set theory, using tools from mathematical logic. A system that gives meaning to the sentences of a formal language is called a model for the language. If a model for a language moreover satisfies a particular sentence or theory (set of sentences), it is called a model of the sentence or theory. Model theory has close ties to algebra and universal algebra.

Mathematical models

Mathematical models can take many forms, including but not limited to dynamical systems, statistical models, differential equations, or game theoretic models. These and other types of models can overlap, with a given model involving a variety of abstract structures.

A more comprehensive type of mathematical model[18] uses a linguistic version of category theory to model a given situation. Akin to entity-relationship models, custom categories or sketches can be directly translated into database schemas. The difference is that logic is replaced by category theory, which brings powerful theorems to bear on the subject of modeling, especially useful for translating between disparate models (as functors between categories).

Scientific models

A scientific model is a simplified abstract view of a complex reality. A scientific model represents empirical objects, phenomena, and physical processes in a logical way. Attempts to formalize the principles of the empirical sciences use an interpretation to model reality, in the same way logicians axiomatize the principles of logic. The aim of these attempts is to construct a formal system for which reality is the only interpretation. The world is an interpretation (or model) of these sciences, only insofar as these sciences are true.[19]

Statistical models

A statistical model is a probability distribution function proposed as generating data. In a parametric model, the probability distribution function has variable parameters, such as the mean and variance in a normal distribution, or the coefficients for the various exponents of the independent variable in linear regression. A nonparametric model has a distribution function without parameters, such as in bootstrapping, and is only loosely confined by assumptions. Model selection is a statistical method for selecting a distribution function within a class of them; e.g., in linear regression where the dependent variable is a polynomial of the independent variable with parametric coefficients, model selection is selecting the highest exponent, and may be done with nonparametric means, such as with cross validation.

In statistics there can be models of mental events as well as models of physical events. For example, a statistical model of customer behavior is a model that is conceptual (because behavior is physical), but a statistical model of customer satisfaction is a model of a concept (because satisfaction is a mental not a physical event).

Social and political models

Economic models

In economics, a model is a theoretical construct that represents economic processes by a set of variables and a set of logical and/or quantitative relationships between them. The economic model is a simplified framework designed to illustrate complex processes, often but not always using mathematical techniques. Frequently, economic models use structural parameters. Structural parameters are underlying parameters in a model or class of models. A model may have various parameters and those parameters may change to create various properties.

Models in systems architecture

A system model is the conceptual model that describes and represents the structure, behavior, and more views of a system. A system model can represent multiple views of a system by using two different approaches. The first one is the non-architectural approach and the second one is the architectural approach. The non-architectural approach respectively picks a model for each view. The architectural approach, also known as system architecture, instead of picking many heterogeneous and unrelated models, will use only one integrated architectural model.

Business process modelling

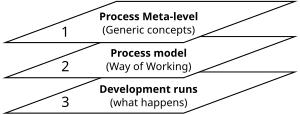

In business process modelling the enterprise process model is often referred to as the business process model. Process models are core concepts in the discipline of process engineering. Process models are:

- Processes of the same nature that are classified together into a model.

- A description of a process at the type level.

- Since the process model is at the type level, a process is an instantiation of it.

The same process model is used repeatedly for the development of many applications and thus, has many instantiations.

One possible use of a process model is to prescribe how things must/should/could be done in contrast to the process itself which is really what happens. A process model is roughly an anticipation of what the process will look like. What the process shall be will be determined during actual system development.[21]

Models in information system design

Conceptual models of human activity systems

Conceptual models of human activity systems are used in soft systems methodology (SSM), which is a method of systems analysis concerned with the structuring of problems in management. These models are models of concepts; the authors specifically state that they are not intended to represent a state of affairs in the physical world. They are also used in information requirements analysis (IRA) which is a variant of SSM developed for information system design and software engineering.

Logico-linguistic models

Logico-linguistic modeling is another variant of SSM that uses conceptual models. However, this method combines models of concepts with models of putative real world objects and events. It is a graphical representation of modal logic in which modal operators are used to distinguish statement about concepts from statements about real world objects and events.

Data models

Entity–relationship model

In software engineering, an entity–relationship model (ERM) is an abstract and conceptual representation of data. Entity–relationship modeling is a database modeling method, used to produce a type of conceptual schema or semantic data model of a system, often a relational database, and its requirements in a top-down fashion. Diagrams created by this process are called entity-relationship diagrams, ER diagrams, or ERDs.

Entity–relationship models have had wide application in the building of information systems intended to support activities involving objects and events in the real world. In these cases they are models that are conceptual. However, this modeling method can be used to build computer games or a family tree of the Greek Gods, in these cases it would be used to model concepts.

Domain model

A domain model is a type of conceptual model used to depict the structural elements and their conceptual constraints within a domain of interest (sometimes called the problem domain). A domain model includes the various entities, their attributes and relationships, plus the constraints governing the conceptual integrity of the structural model elements comprising that problem domain. A domain model may also include a number of conceptual views, where each view is pertinent to a particular subject area of the domain or to a particular subset of the domain model which is of interest to a stakeholder of the domain model.

Like entity–relationship models, domain models can be used to model concepts or to model real world objects and events.

See also

- Concept

- Concept mapping

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual model (computer science)

- Conceptual schema

- Conceptual system

- Information model

- International Conference on Conceptual Modeling

- Interpretation (logic)

- Isolated system

- Ontology (computer science)

- Paradigm

- Physical model

- Process of concept formation

- Scientific modeling

- Theory

References

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, archived from the original on 2020-10-10, retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ^ Tatomir, A.; et al. (2018). "Conceptual model development using a generic Features, Events, and Processes (FEP) database for assessing the potential impact of hydraulic fracturing on groundwater aquifers". Advances in Geosciences. 45: 185–192. Bibcode:2018AdG....45..185T. doi:10.5194/adgeo-45-185-2018.

- ^ Gregory, Frank Hutson (January 1992) Cause, Effect, Efficiency & Soft Systems Models Warwick Business School Research Paper No. 42. With revisions and additions it was published in the Journal of the Operational Research Society (1993) 44(4), pp. 149–68.

- ^ Mylopoulos, J. "Conceptual modeling and Telos1". In Loucopoulos, P.; Zicari, R (eds.). Conceptual Modeling, Databases, and Case An integrated view of information systems development. New York: Wiley. pp. 49–68. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.83.3647.

- ^ "C.H. Kung, A. Solvberg, Activity Modeling and Behavior Modeling, In: T. Ollie, H. Sol, A. Verrjin-Stuart, Proceedings of the IFIP WG 8.1 working conference on comparative review of information systems design methodologies: improving the practice. North-Holland, Amsterdam (1986), pp. 145–71". Portal.acm.org. Retrieved 2014-06-20.

- ^ Sokolowski, John A.; Banks, Catherine M., eds. (2010). Modeling and Simulation Fundamentals: Theoretical Underpinnings and Practical Domains. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470590621. ISBN 9780470486740. OCLC 436945978.

- ^ I. Davies, P. Green, M. Rosemann, M. Indulska, S. Gallo, How do practitioners use conceptual modeling in practice?, Elsevier, Data & Knowledge Engineering 58 (2006) pp.358–80[dead link]

- ^ Davidson, E. J. (1999). "Joint application design (JAD) in practice". Journal of Systems and Software. 45 (3): 215–23. doi:10.1016/S0164-1212(98)10080-8.

- ^ a b c Gemino, A.; Wand, Y. (2004). "A framework for empirical evaluation of conceptual modeling techniques". Requirements Engineering. 9 (4): 248–60. doi:10.1007/s00766-004-0204-6. S2CID 34332515.

- ^ Gemino, A.; Wand, Y. (2003). "Evaluating modeling techniques based on models of learning". Communications of the ACM. 46 (10): 79–84. doi:10.1145/944217.944243. S2CID 16377851.

- ^ Herbert Stachowiak: Allgemeine Modelltheorie, 1973, S. 131–133.

- ^ Thalheim: Towards a Theory of Conceptual Modelling. In: Journal of Universal Computer Science, vol. 16, 2010, no. 20, S. 3120

- ^ Dietrich Dörner: Thought and Design – Research Strategies, Single-case Approach and Methods of Validation. In: E. Frankenberger et al. (eds.): Designers. The Key to Successful Product Development. Springer-Verlag, Berlin et al. 1998, S. 3–11.

- ^ M. Weisberg: Simulation and Similarity - using models to understand the world. Oxford University Press, New York NY 2013

- ^ Mental Representation:The Computational Theory of Mind, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, [1]

- ^ Mental Models and Usability, Depaul University, Cognitive Psychology 404, Nov, 15, 1999, Mary Jo Davidson, Laura Dove, Julie Weltz, [2] Archived 2011-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Slater, Matthew H.; Yudell, Zanja, eds. (2017). Metaphysics and the Philosophy of Science: New Essays. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780199363209. OCLC 956947667.

- ^ DI Spivak, RE Kent. "Ologs: a category-theoretic approach to knowledge representation" (2011). PLoS ONE (in press): e24274. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024274

- ^ edited by Hans Freudenthal (1951), The Concept and the Role of the Model in Mathematics and Natural and Social Sciences, pp. 8–9

- ^ Colette Rolland (1993). "Modeling the Requirements Engineering Process." in: 3rd European-Japanese Seminar on Information Modelling and Knowledge Bases, Budapest, Hungary, June 1993.

- ^ C. Rolland and C. Thanos Pernici (1998). "A Comprehensive View of Process Engineering". In: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference CAiSE'98, B. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 1413, Pisa, Italy, Springer, June 1998.

Further reading

- J. Parsons, L. Cole (2005), "What do the pictures mean? Guidelines for experimental evaluation of representation fidelity in diagrammatical conceptual modeling techniques", Data & Knowledge Engineering 55: 327–342; doi:10.1016/j.datak.2004.12.008

- A. Gemino, Y. Wand (2005), "Complexity and clarity in conceptual modeling: Comparison of mandatory and optional properties", Data & Knowledge Engineering 55: 301–326; doi:10.1016/j.datak.2004.12.009

- D. Batra (2005), "Conceptual Data Modeling Patterns", Journal of Database Management 16: 84–106

- Papadimitriou, Fivos. (2010). "Conceptual Modelling of Landscape Complexity". Landscape Research, 35(5):563-570. doi:10.1080/01426397.2010.504913

External links

- Models article in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy