William James (slave trader)

William James (1735–1798) was an English slave trader, plantation owner and slave owner.[1][2]

Slave trader

William James was responsible for at least 144 slave voyages. He was active in the years between 1758 and 1778 from the Port of Liverpool.[2]

Slave owner

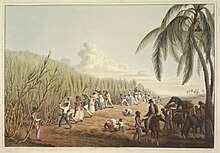

William James owned enslaved people on three plantations in Jamaica: Cambridge Pen, Clifton Hill, and Malborough Mount.[1]

Personal life

William James was the grandfather of a 19th-century member of parliament for Carlisle, who was also called William James. William James (the slave trader) left his grandson plantations with their enslaved people and financial wealth in his will.[3]

Sailor riot

William James was one of the biggest slave traders of his era.[4] He operated out of the Port of Liverpool and was well known amongst the sailors, ship builders and the many tradespeople working at the docks. In August 1775 a large scale sailors' riot broke out in Liverpool. A number of sailors had been employed to fit out the rigging for a ship called Derby. The owners refused to pay the full amount contracted, on the basis that there were so many unemployed sailors currently at the dock. The sailors were angered, they returned to the Derby and cut the rigging down, resulting in a number of them being arrested. 2,000 sailors armed with spikes and clubs broke them out of jail.[5] The sailors then returned to Liverpool docks and cut the rigging of all of the ships ready to set sail. James at one time owned 29 ships at the port.[4]

The owners of the Derby agreed to pay the wages due and the sailors spent the rest of the day drinking alcohol and celebrating. The sailors then heard that there was a bounty on the leaders of the rioters, so they broke into a gun shop and stole 300 muskets and took cannons from the docks. They then went to Liverpool Town Hall, which housed the Liverpool Exchange on the ground floor and the Town Hall upstairs. The sailors spent most of the day shooting the cannons and muskets at the building, causing carnage.[6] An eyewitness wrote the people were petrified and described the fear on the faces of the merchants in the town. The sailors marched on the dock merchant's homes to exact revenge. William James, had been forewarned and fearing for his life left Liverpool to stay at his country retreat.[4] He took his family, servants and valuables but left a sole African boy who was found hiding in a clock. The sailors ransacked his home, breaking the crockery, shredding his fine bedding, drinking or pouring away the liquor in his cellar, destroying his compting house and destroying his furniture.[7] The riot was eventually quelled by a troop of light horse guards from Manchester. At least 7 people died and dozens were injured. In April 1776, 14 of the rioters were transported to America as punishment. Gomer Williams writes "the annals of the eighteenth century probably cannot mention a more extraordinary and formidable popular outbreak in England than these riots, arising from the greed of slave-merchants and the ferocity of their hirelings, and in which cannon, muskets, pistols, cutlasses and other deadly weapons were freely used by the mob.[8]

References

- ^ a b "Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slavery". www.ucl.ac.uk.

- ^ a b Richardson 2007, p. 201.

- ^ "Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slavery". www.ucl.ac.uk.

- ^ a b c Williams 1897, p. 557.

- ^ Williams 1897, p. 558.

- ^ Williams 1897, p. 559.

- ^ Williams 1897, p. 558-560.

- ^ Williams 1897, p. 560.

Sources

- Richardson, David (2007). Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-066-9.

- Williams, Gomer (1897). History of the Liverpool Privateers. UK: Liverpool University Press.