Salonika Incident

The Salonika Incident was a major diplomatic incident that broke out on 6 May 1876 after a mob murdered the consuls of France and German Empire in the Ottoman city of Salonica, Jules Moulin and Henry Abbott. After a young Orthodox Christian woman of Bulgarian origin[1] attempted to convert to Islam to marry a Turk against the will of her family, she was detained by the US Consul at Thessaloniki. An enraged mob attempted to retrieve the woman, and murdered Moulin and Abbott when it failed to find her. A diplomatic backlash ensued, leading to displays of force and to reforms in the Ottoman Empire.

Background

In the 1820s, a number of incidents leading to the death of Christians occurred in the Ottoman Empire, notably the Constantinople massacre of 1821, marking the European opinion.[2] The exactions of the bashi-bazouk compounded this sentiment in the following decades.[3] On 15 June 1858, rioting in Jeddah, believed to have been instigated by a former police chief in reaction to British policy in the Red Sea, led to the massacre of 25 Christians, including the British and French consuls, members of their families, and wealthy Greek merchants,[4][5] yielding a two-day retaliation bombardment from the British frigate HMS Cyclops.[6] The declining Ottoman Empire was also relying more and more on European investment and loans even for daily expenditure, which the European public opinion resented as it was perceived that the funds were squandered in inefficient projects and in corruption, contributing to the poor image of the Empire.[7] Finally, the Sublime Porte was entering a period of such political instability that 1876 would become known as the "Year of Three Sultans".[8]

At that time, a Bulgarian notable, Pericles Hajji Lazzaro, acted as US Consul in Thessaloniki (Salonika).[9] The German consul in Thessaloniki was Sir Henry Abbott, a British subject of Orthodox Christian faith. His brothers were George Abbott and Alfred Abbott.[10] The French consul was Jules Moulin. Jules Moulin had married Henry Abbott’s sister, and they were thus all tied by familial links.[9]

On 3 May 1876,[11] a 16-year-old girl named Stephana, was abducted by several women.[12] Stephana, from Bogdanci, near Gevgelija, was of Bulgarian and Christian heritage, but probably had a muslim lover[13] against the will of her family. Stephana associated with a neighbouring Turkish and Muslim family, which took her in their home[12] and proposed to bring her to Thessaloniki in order to complete administrative paperwork that would officially enact her conversion to Islam.[2] To do so, Ottoman law required the convert to appear before a local council and testify that they were embracing Islam freely, as a sane adult and without coercion.[14] The Turks gave Stephana a traditional attire, comprising a full coat and a veil, and brought her to Gevgelija where she would take the train to Thessaloniki.[15] When the train stopped at Karasuli, Stephana's mother Maria was there and recognised her daughter, whom she tried to convince not to follow through with her conversion to Islam.[16]

The train arrived at Thessaloniki in the morning of 5 May.[16] As Stephana asked policemen to escort her to the governor's residence, her mother called for help from Christian bystanders;[10] as the day was an Orthodox holiday, a 150-strong group of Christians happened to be at the station, including George Abbott, and they attacked Stephana's companions.[10] They seized her, removed her traditional Turkish clothes, put her in a carriage and took her to Hajji Lazzaro's residence.[9][10]

On the next day, a mob gathered to demand that the Consul hand over Stephana to them. [2]

Incident

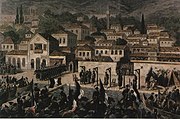

In the morning of 6 May, a crowd started assembling in front of the Governor's residence. As rumours ran wild, people grew restless, prompting the Chief of Police, Colonel Salim Bey, to call for the crowd to calm down and disperse.[17] The authorities attempted bring calm by claiming that Stephana would be freed shortly, but as the hours passed and the Governor remained empty-handed, the crowd turned into an angry mob,[18] with calls for marching on the US Consulate and free Stephana by force.[19]

Around 15:00 on 6 May, the consuls of France and Germany, Abbott and Moulin, learned of the commotion in the city. They decided to go to the governor, Mehmed Refet Pasha,[20] either to further negotiate about the conversion of Stephana or to assess the situation on the ground.[19] Abbott and Moulin found themselves surrounded by the mob, and taken to a building adjacent to a mosque, where they found a precarious refuge from the crowd, and the very relative protection of a handful of policemen.[21] Abbott then wrote a letter to Hajji Lazzaro, urging him to release Stephana immediately, but the mob stopped the messenger and destroyed the letter.[22] Seeing that the letter was ineffectual and that the authorities had no assistance forthcoming either from the artillerymen of the citadel or from the marines of the ironclad Iclaliye at anchor in the harbour,[19] Abbott wrote a second message to his brother.[23]

Meanwhile, the British Consul, J.E. Blunt, learning of the ongoing incident, sent a message of his own to Abbott's brothers, and rushed to the scene of the incident. There, witnessing the severity of the situation, he write another message to Hajji Lazzaro, also urging him to lead Stephana to the mosque.[24]

After three quarters on an hour, the mob started breaking into the room where the consuls where surrounded, by dislodging the iron bars that protected the windows.[25] The crowd invaded the building, broke into the room and lynched Abbott and Moulin with these very iron bars, in front of Mehmed Refet Pasha, Salim Bey and a few policemen, who were helpless in protecting the consuls.[26] The corpses were further mutilated after the two men were killed.[26][27][28]

Soon afterwards, policemen arrived, escorting Stephana. When the rioters confirmed her identity, the crowd dispersed.[29] The mob thus ceased to threaten the Christian quarters of the city, and allowed the Pasha to extend his protection to Hajji Lazzaro.[9] Blunt telegraphed the news of the incident and of the murders to the British embassy in Constantinople and, warning that the local authorities did not have the necessary forces to maintain order, requested the protection of the Royal Navy. [27]

Aftermath

The governments of Europe instrumentalised the incident to embarrass the Ottoman Empire,[2] issuing an ultimatum demanding improvements in the security of foreigners,[9] as well as harsh and swift punishment for those responsible.[2] Warships deployed in the Mediterranean as a show of force to back the demands.[2][9]

By 14 May, the port of Thessaloniki harboured the Ottoman warships Edirne, Iclaliye, Selimiye, Sahir and Muhbîr-i Surure; the Greek Salaminia and Vasilefs Georgios; the French Gladiateur and Châteaurenault; the British HMS Bittern and Swiftsure; the Russian Ascold; and the Italian Regina Maria Pia, and well as another Italian gunboat.[30]

The Sultan replaced Refat Pasha with Sherif Pasha as governor, and sent troops in to maintain order. They arrested 50 people, of whom six were publicly executed without a trial. Several public officers were demoted and some were sentenced to hard labour. The Ottoman Empire furthermore paid 40 000 English pound compensations to the families of the victims.[9]

Sources and references

References

- ^ One example is an international incident that erupted in Salonika in May 1876. A young Bulgarian woman arrived by train from Skopje and begged gendarmes in the station to take her to the authorities so she could convert to Islam. For more see: Howard, Douglas A. History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521898676, 2017. p. 256.

- ^ a b c d e f "'Murder in Salonika, 1876' by Berke Torunoğlu". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 12

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 17

- ^ Caudill, Mark A. (2006). Twilight in the kingdom : understanding the Saudis. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Security International. p. 133. ISBN 9780275992521.

- ^ Bosworth, C. Edmund (2007). Historic cities of the Islamic world. Leiden: Brill. p. 223. ISBN 9789004153882. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 24

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 25

- ^ a b c d e f g "Thessaloníki, Greece - vol1, chapter 14". www.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ a b c d Torunoğlu (2009), p. 33

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 28

- ^ a b Torunoğlu (2009), p. 30

- ^ Torunoğlu, Berke (2009). "Murder in Salonika, 1876 : a tale of apostasy turned into an international crisis".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 27

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 31

- ^ a b Torunoğlu (2009), p. 32

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 37

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 38

- ^ a b c Torunoğlu (2009), p. 39

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 36

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 40

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 41

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 42

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 43

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 44

- ^ a b Torunoğlu (2009), p. 45

- ^ a b Torunoğlu (2009), p. 47

- ^ The Murder of Consuls in Turkey, The Illustrated London News, 17 June 1876

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 46

- ^ Torunoğlu (2009), p. 67

Bibliography

- Torunoğlu, Berke (2009). "Murder in Salonika, 1876: a tale of apostasy turned into an international crisis" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Torunoğlu, Berke (2012). Murder in Salonika, 1876: A Tale of Apostasy and International Crisis. Libra Books.

- Mazover, Mark (2004). Salonica, city of Ghosts - Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780375412981.

External links

- The Murder of Consuls in Turkey, The Illustrated London News, 17 June 1876

- Chapter Fourteen, In Memorium of Salonike; The Greatness and Destruction of Jerusalem of the Balkans: The Activities of Allatini and Modiano, Translated by Judy Montel

- The Abbott Brothers of Salonica

- ‘Murder in Salonika, 1876’ by Berke Torunoğlu, William Armstrong