Hino Kunimitsu

Hino Kunimitsu 日野 邦光 | |

|---|---|

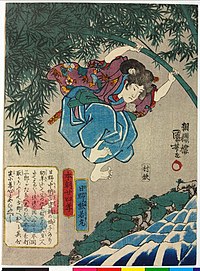

Kumawaka plotting to assassinate Homma Saburō, as imagined by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. | |

| Born | 14th century |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Occupation | ninja |

| Known for | Kumawakamaru 熊若丸 |

Hino Kunimitsu (日野 邦光) (14th century), or Hino Kumawaka (日野 熊若), childhood name Kumawakamaru (熊若丸), was the son of Hino Suketomo, the dainagon (high counselor) to Emperor Go-Daigo. Kumawaka himself was also an attendant to Emperor Go-Daigo. He is best known for avenging his father by killing the lay monk Homma Saburō, who had Suketomo executed. Later, Kumawaka was sometimes portrayed in art as an example of filial piety.

Chronicle

[edit]Much of what is known about Kumawaka comes from the 14th century chronicle Taiheiki.

As the story goes, Kumawaka's father, Suketomo dainagon, had been exiled to the island of Sado. Suspecting a conspiracy by the Imperial court, the Kamakura shogunate named Suketomo a major co-conspirator, and called for his execution. This order was relayed to the lay monk Homma Saburō, who presided over Sado island. The thirteen-year-old Kumawaka, who was in hiding at Ninna-ji, a main buddhist temple, caught wind of this news and traveled to Sado to be with his father one final time.[1]

Having arrived at Sado island, he was granted an audience with Homma Saburō. However, Homma would not let Kumawaka see his father, but instead had him lodged in a nearby residence.[2] Eventually, Suketomo was beheaded before Kumawaka got the chance to meet him. Kumawaka was entrusted with his father's cremated remains, and he had them delivered to Mount Kōya. Following this, Kumawaka feigned illness, and lay for several days in Homma's residence. During this time, he plotted his father's revenge.[3]

Revenge

[edit]

One night, Kumawaka snuck out unarmed, expecting to kill Homma's son. Instead, he came upon Homma himself, asleep in a different room. In the room, a lamp was burning brightly, and Kumawaka feared that disturbing the light would wake the monk. To solve this, he opened the door slightly, allowing moths to swarm in and extinguish the light.[5] He picked up Homma's sword, but kicked his pillow to awaken the monk, thinking, "...to kill a sleeping man is no different than stabbing a corpse".[5] When Homma woke up, Kumawaka stabbed him in the chest and throat, and fled to hide in a bamboo grove. The guards, seeing small bloodstained footprints, went out in search of him. Faced with a deep moat, Kumawaka climbed onto a bamboo, and weighed down the tip of the plant, allowing him to drop over on the other side.[4] He then headed for the harbor for a ship to take him back to the main islands.

Escape

[edit]

During the day, he hid in a field of hemp, where he observed over a hundred mounted men searching for him.[4] Eventually, he came across an old monk, who, after listening to Kumawaka's story, carried him on his back to the harbor.[6] At the harbor, the pair had great difficulty in finding a boat. When one vessel refused to heed the old monk's pleas for passage, the monk began chanting a prayer for the vessel to return. According to the text, a violent wind then appeared, threatening to capsize the boat.[6] Seeing this, the boatmen cried out to the old monk to save them, and rowed back to shore. When they reached the shore, the winds calmed, and Kumawaka and the old monk got on the boat. The mounted pursuers had now caught up with them, and rode out onto shallow water in pursuit. However, the boat crew, ignoring their shouts, raised sails and journeyed safely to Echigo province.[7]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ McCullough 2004, pp. 44–45

- ^ McCullough 2004, p. 46

- ^ McCullough 2004, p. 47

- ^ a b c McCullough 2004, p. 49

- ^ a b McCullough 2004, p. 48

- ^ a b McCullough 2004, p. 50

- ^ McCullough 2004, p. 51

References

[edit]- Leupp, Gary P. (1997), Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-20900-8

- McCullough, Helen Craig (2004), The Taiheiki: A Chronicle of Medieval Japan, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8048-3538-1

- Shirane, Haruo (2008), Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-14415-5