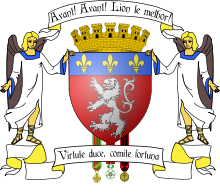

Coat of arms of Lyon

| Coat of arms of Lyon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Versions | |

Escutcheon-only | |

| Armiger | City of Lyon |

| Adopted | 1320 (documented) 1859 (current version) |

| Crest | A mural crown Or. |

| Shield | Gules a lion rampant Azure. Upon a chief of Azure three fleur-de-lys Or. |

| Supporters | two branches of mulberry with silver fruit and full of worms, butterflies and silk buds |

| Order(s) | the cross of the Legion of Honour, the Croix de Guerre 1914-1918 and the Resistance Medal |

The coat of arms of Lyon, the ancient capital of the Gauls, reflects the rich history of the city across different periods of its existence and the power that has exercised authority over the city. It was created in 1320, although the current version, which dates from 1859, reprises the form that it had before the end of the Ancien Régime after having undergone several temporary modifications.

Its heraldic description is the following one:

In gules field, a rampant lion of silver, increased of a head of azure laden with three flowers of gold lilies. The whole surrounded by two branches of mulberry, fruity silver and full of worms, butterflies and silk buds. To the crest, a mural crown of four towers, three in sight, of gold. Protruding from the point, the cross of the Legion of Honor, the one of War 1914-1918 and the Medal of Resistance, all in their color.

The blazon proper of Lyon consists of a field of gules (red color), in which a lion appears rampant (of profile and erect) and silver (white color). The shield itself is augmented by a heraldic chief, the division occupying the upper third. This is the "Head of France", which shows the heraldry of his former monarchs: of azure laden with three golden fleurs-de-lys (a blue background adorned with three yellow lily flowers).[1]

In the crest, a French mural crown of gold is shown. The mural crown, of Roman origin, is often used by municipal corporations as an emblem of their power and authority. Surrounding the arms is a crown formed by two branches of mulberry or oak. A decree, dated 26 November 1946, established that it would adorn the coat of arms with the decorations granted to Lyon: the Cross of the Legion of Honour, the French Cross of War 1914-1918 and the Resistance Medal.[2]

The shield of the city was granted in 1320, when Lyon was included the list of «Bonnes Villes» of the king of France. The armories with the silver lion in a field of gules, which used the ancient counts of Lyon, were augmented with the old "Head of France" (strewn with gold fleurs-de-lis).[3] In 1376, King Charles V of France simplified its shield by reducing the number of fleurs de lis to three. This change was introduced in the heraldic chiefs of all the "Bonnes Villes". The current design was adopted in 1859.

History of the coat of arms of Lyon

Pre-heraldic times

The birth of heraldry and the formation of the first coats of arms as a distinctive mark of individuals (noble or not) and the organizations of cities or corporations only dates from the 12th century, but one can find, however, traces of a symbol of the city's arms called De geules au chef de Bourgogne, that is, a red shield surmounted by a haorizontal band with the diagonal striped colors of the Kingdom of Burgundy, which were gold and blue starting in the fifth century.[4] Essentially, during this era, Lyons made up part of the Kingdom of Burgundy born in the aftermath of the fall of the Western Roman Empire and which made up the three great French kingdoms with Austrasia and Neustria, where the Merovingians ruled.

One finds on these original arms the champ de gueule (red field or background), which would be the foundation for all subsequent coats of arms of Lyons.

The counts of Lyon

In the tenth century, the counts of Lyons were the sovereign rulers of the city of Lyons which coalesced during the time of the Kingdom of Burgundy, then in the Holy Roman Empire after 1058. These counts of Lyons took for their emblem De gueules au lion d'argent.[5] The name of the city of Lyons has no link with the animal lion, as it comes from the Latin name Lugdunum of which the root Lug- could also have been attached, like the Latin Lux ("light") or the Gaulish Lugos ("bracket") to the other root dunum, which means "hill." But the linguistic closeness which is noted today between the animal and the name of the city could have given inspiration to the arms parlantes, that is, the imagistic content gives in rebus the name of the cities that they designate. In the 12th century, the Archbishop of Lyons regained the title of Count and exercised temporal power as well as spiritual over the city. During this time the city carried the emblem of the counts of Lyons.

The union with France

The relationship between the bourgeois residents and the archbishop of Lyons often intersected with the subject of communal freedom at the beginning of the 14th century. King Philip IV of France, interested in this city on the frontier of his kingdom, came to settle conflicts and eventually de facto to annex the city, an action confirmed by the Council of Vienne in 1312. In 1320, he gave the city a municipal charter, under which it would be governed by 12 consuls and, as a symbol of his protection, be granted a chef de France (French heading) to its coat of arms. This heading was stitched onto the arms in order to avoid the rule of heraldry which prohibited the bordering of a color against another color (red against blue) on a coat of arms.

The French heading, which is a blue band studded with fleur-de-lis, was a privilege which the King of France accorded to "good cities of France," which were loyal to him during the Middle Ages, before they were instituted all over the coats arms of municipalities in France at the end of the Ancien Régime. These cities had the privilege of being represented at the coronation of French kings. This addition corresponded with the coat of arms of France itself.

Furthermore, the coat of arms of Lyons followed the evolution of the royal coat of arms of France, which at its outset was described as D'azur semé de fleurs de lys, that is, blue with a significant number of fleur-de-lis arrayed on the shield. The French heading accorded in 1320 was thus also studded with fleur-de-lis. In 1376, however, King Charles V of France simplified his arms and reduced the number of fleur-de-lis to just three. The arms of Lyons followed suit, being simplified to use a heading with only three floral emblems. The coat of arms as thus modified is the coat of arms of the city today and that which has been used for the longest stretch of the city's history.

French Revolution and First French Empire

The French Revolution which began in 1789 suppressed the coats of arms which were considered symbols of the Ancien Régime, which had been overthrown. There were thus no coats of arms of Lyons that represented the city during the First French Republic. The representatives of the city wanted to use a shield carrying only a goddess of Liberty. In 1793, following the Revolt of Lyon against the National Convention, "Lyon n'est plus" (Lyons was no more), as the city as an institution was officially disestablished.

The First French Empire re-established the city and gave it arms like all the other cities in France by the decree of 1809 and changed only the fleur-de-lis at its head into three bees oriented upwards.[6] The bees are symbols of Napoléon I and the Empire itself and came to replace the fleur de lis as a symbol of France in different heraldic contexts. The arms were thus officially described: "De gueules au lion d'argent au chef des bonnes villes de l'Empire (de gueules à trois abeilles d'or)."

The Restoration and the July Monarchy

The French Restoration in 1815 again changed the coat of arms of France and Louis XVIII permitted French cities to resume using the arms that they had employed before the Revolution. This returned the three fleur-de-lis to the head of the arms of Lyons.

Otherwise, the king augmented through letters-patent of 27 February 1819 the arms of the city with a sword carried in the right paw of the lion in order to commemorate the siege of Lyons the city had endured for the royal cause in 1793 and in recognition of the combativeness of the city in the armed struggle against the Revolution.[7]

Following the Three Glorious Days in July 1830 which overthrew King Charles X of France, the July Monarchy was installed and renounced the traditional royal coat of arms with the blue field studded with three fleur-de-lis in 1831 in order to symbolize the adhesion of the monarchy to a parliamentary system. As such, the fleur-de-lis on the coat of arms of Lyons were changed to three gold stars.

From 1848 to the present

The short-lived Second French Republic was not interested in using coats of arms. Under the Second French Empire, the keeper of the seals asked Senator Vaïsse in 1859 to resume the use of the coat of arms carrying only the lion and the fleur-de-lis, but this modification was not adopted by the municipal council of Lyons until the beginning of the twentieth century. In the interim, under the Third Republic, a number of fantastical emblems flourished, with many adding elements or changing the position of the lion.[8]

The city of Lyons uses thus at the beginning of the 21st century the arms which it has carried for six centuries: De gueules au lion rampant armé, lampassé d'argent au chef d'azur chargé de trois fleurs de lys d'or.

Ornaments

The ornaments outside the shield do not, properly speaking, make up part of the coat of arms and are not described in the heraldry, even if eventually they are codified. They are situated around the shield itself.

- The walled crown: The walled crown symbolizes the fortifications of the ancient cities but their addition on the shield generally only dates from the First Empire. Napoléon Bonaparte accorded the city a walled crown with seven gold crenellations, a symbol of the cities fortified from Antiquity.

- The War Cry: The cry is represented traditionally on a ribbon above the shield: "Il servait autrefois de signal, soit pour livrer le combat ou se reconnaître dans la mêlée, soit pour rallier les troupes et ranimer leur courage" (It serves otherwise as a signal, either to begin combat or for soldiers to be recognized in the melée, or to rally the troops and restore their courage.)[9] For example, Montjoie-Saint-Denis would be the war cry of the kings of France, as Notre Dame Guesclin would be that of the constable Bertrand Du Guesclin. The war cry of the city of Lyons in the francoprovençal dialect which is documented from 1723 is "Avant, Avant, Lion le melhor!" This exhortation is, however, regularly confused with the motto and is frequently associated with the arms of the city in the representations on the ribbon under the shield.

- The motto: The motto is represented traditionally in heraldry as written on a ribbon under the shield. The motto of the city of Lyons is traditionally Virtute duce, comite fortuna ("Led by virtue, accompanied by good fortune"), quotations from Cicero to Lucius Munatius Plancus, the founder of Lyons. One finds, however, also other mottoes such as Fortitudine ac (or et) prudentia (From force and prudence).

- The supporting elements: The supporting ornaments are animals or figures (often mythological) who support the shield. In the ancient representations, the shield of Lyons is often represented alone or shared between two "angels" or "spirits."[10] But modern usage often undergirds the arms of cities with oak branches or laurel wreaths, etc.

- The decorations: The city of Lyons received over the course of the 20th century several decorations which it could represent in its coat of arms. The city was awarded the cross of the Knight of the Legion of Honor by decree of 26 November 1946 with the Croix de Guerre of 1939-45 and the Resistance Medal with a rose.[11]

The origin of the lion in the arms of Lyons

The name of Lyons has no link with the animal, but derives from the Latin name of the city Lugdunum, which was progressively reduced to Lyduum, and then Lyons. This homonym, completely by chance, has influenced the choice of a lion as a symbol of the city and the formation of "speaking arms." But this resemblance is not the only origin of the lion of Lyons, though it was used as an emblem of the city beginning in antiquity. It is possible that it had been adopted in honor of Mark Antony, who himself had used the emblem. Mark Antony had traveled in Gaul with Julius Caesar, for whom Antony had been the treasurer of the army during the Gallic Wars, and Celtic Gaul had been retaken by him during the partitioning of Roman lands by the Second Triumvirate as constituted with Lepidus and Octavian. He had been one of the benefactors of the city, which had been founded shortly beforehand. The mint at Lugdunum which had the privilege of striking money released at least about 43 BC a quinarius of Mark Antony with the head of Victory turned to the right and on the reverse a lion walking and the inscription LUGUDUNI A XL (Lyons, 40th year) for its 40th anniversary. Thus, in the same manner as the wolf of Rome or the crocodile of Nîmes, it seems that the lion has been associated with Lyons since ancient times. Later, it also served as a symbol of the bourgeois citizens of Lyons in their struggles against the power of the archbishop.

As a consequence of the presence of the lion in its coat of arms, on 10 July 1584 the city was offered a real lion by François de Mandelot, governor of the Lyonnais. The consulate thanked the donor but refused the gift, as it did not have funds for its upkeep in the middle of the Wars of Religion.

Arms of the city as a municipality

The history presented here of the different coats of arms traditionally used in order to describe the city of Lyons in the sense that the sovereign, that is, the count of Lyons, was merged with those of the city. Technically, it was not until 1320, when the archbishop Pierre IV of Savoy accorded a charter that instituted the consulate, that the city possessed its own arms as a municipality, which were those of the counts of Lyons to whose temporal power the consulate had succeeded.[12]

At the beginning of the 15th century, the presence of the lion in the arms of the city was the subject of a trial. The archbishop of Lyons, Amédée II de Talaru, who was at the time on unfriendly terms with the city's aldermen, decided to remove the lion from the arms of the city, thus depriving it of its most noble element, in arguing that the lion had been given by the archbishops-counts of Lyon since it was the arms of the counts of Lyon and thus it was the right of the archbishop to reclaim it.

As it happened, the archbishop had the will to modify the arms of the city as he believed he had the right to do, but the aldermen appealed to King Charles IV who sided with them and carried the affair before the Parlement when the archbishop refused to execute the royal order. By this decision, the authorities confirmed the full ownership of the municipality to the arms of the city.

Stamps

The shield of Lyons is illustrated on a postage stamp of 70 centimes (Armoiries de villes, 3rd series 1958).

References

- ^ "Les armoiries de Lyon" (in French). Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "69 300 - Lyon". L'armorial des villes et des villages de France (in French). Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Lion et Lyon". Le Guichet du Savoir (in French). Lyon: Public Library of Lyon. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Histoire du blason de Lyon sur @Lyon et Guichet du Savoir[permanent dead link], Blason de Lyon.

- ^ "Le blason au fil des siecles - Site Officiel de la Ville de Lyon". Archived from the original on 2005-10-25. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- ^ http://www.euraldic.com/txt_vbh002_lyon.html (in French)

- ^ Archives historiques et statistiques du département du Rhône, tome VII, 1827 (lire en ligne [1]), note at the bottom of page 339-340 (in French).

- ^ Guichet du Savoir [2][permanent dead link] [archive], Blason de Lyon.

- ^ Jouffroy d'Eschavannes, Traité complet de la Science du Blason à l'usage des Bibliophiles, Archéologues, Amateurs d'objets d'art et de curiosité, Numismates, Archivistes Archived 2011-12-28 at the Wayback Machine, Paris, 1885 (in French).

- ^ Archives historiques et statistiques du département du Rhône, Tome VII, p. 337. (in French)

- ^ Chemins de mémoire.

- ^ Guichet du Savoir [3][permanent dead link], Blason de Lyon.

External links

- Armes de Lyon (in french)

- Les blasons de Lyon (en francés)