Effect of Sun angle on climate

The amount of heat energy received at any location on the globe is a direct effect of Sun angle on climate, as the angle at which sunlight strikes Earth varies by location, time of day, and season due to Earth's orbit around the Sun and Earth's rotation around its tilted axis. Seasonal change in the angle of sunlight, caused by the tilt of Earth's axis, is the basic mechanism that results in warmer weather in summer than in winter.[1][2][3] Change in day length is another factor.[2][3]

Geometry of Sun angle

This diagram illustrates how sunlight is spread over a greater area in the polar regions. In addition to the density of incident light, the dissipation of light in the atmosphere is greater when it falls at a shallow angle.

One sunbeam one mile wide shines on the ground at a 90° angle, and another at a 30° angle. The one at a shallower angle covers twice as much area with the same amount of light energy.

Figure 1 presents a case when sunlight shines on Earth at a lower angle (Sun closer to the horizon), the energy of the sunlight is spread over a larger area, and is therefore weaker than if the Sun is higher overhead and the energy is concentrated on a smaller area.

Figure 2 depicts a sunbeam one mile (1.6 km) wide falling on the ground from directly overhead, and another hitting the ground at a 30° angle. Trigonometry tells us that the sine of a 30° angle is 1/2, whereas the sine of a 90° angle is 1. Therefore, the sunbeam hitting the ground at a 30° angle spreads the same amount of light over twice as much area (if we imagine the Sun shining from the south at noon, the north–south width doubles; the east–west width does not). Consequently, the amount of light falling on each square mile is only half as much.

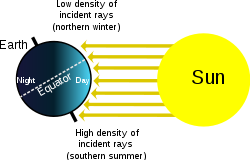

This is a diagram of the seasons. Regardless of the time of day (i.e. Earth's rotation on its axis), the North Pole will be dark, and the South Pole will be illuminated; see also arctic winter.

Figure 3 shows the angle of sunlight striking Earth in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres when Earth's northern axis is tilted away from the Sun, when it is winter in the north and summer in the south.

Technical note

Heat energy is not received from the Sun. Rather, radiant energy is received and this results in change in energy level of receiving bodies in Earth's domain. Different materials have different properties for transmitting back received energy in the form of heat energy at different rates.

See also

- Axial tilt

- Declination

- Solar irradiance (insolation)

- Sun path

References

- ^ Windows to the Universe. Earth's Tilt Is the Reason for the Seasons! Archived 2007-08-08 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-06-28.

- ^ a b Khavrus, V.; Shelevytsky, I. (2010). "Introduction to solar motion geometry on the basis of a simple model". Physics Education. 45 (6): 641. Bibcode:2010PhyEd..45..641K. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/45/6/010. S2CID 120966256. Archived from the original on 2016-09-16. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- ^ a b Khavrus, V.; Shelevytsky, I. (2012). "Geometry and the physics of seasons". Physics Education. 47 (6): 680. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/47/6/680. S2CID 121230141.