Selig Zoo

| Selig Zoo | |

|---|---|

Selig Zoo archway, 1955 | |

| |

| 34°04′03″N 118°12′03″W / 34.0676°N 118.2009°W | |

| Date opened | 1915 |

| Date closed | c. 1940 |

| Location | 3800 Mission Road, Lincoln Park, Los Angeles, California |

The Selig Zoo in Los Angeles, California was an early 20th century animal collection managed by Col. W.N. Selig for use in Selig Polyscope Company films and as a tourist attraction. Over the years the zoo was also known as the Luna Park Zoo, California Zoological Gardens, Zoopark, and, eventually, Lincoln Amusement Park. After Westerns, "animal pictures" were Selig's second-most popular genre of film product.[1]

History

According to Haenni, "Selig became the owner of Big Otto Breitkreutz's circus after the latter was unable to repay a debt, and a Selig troupe spent the winter of 1910–11 making films in Florida..."[1] By December 1911,[2] Selig had gathered a large collection of animals for his films so he bought 300 acres (0.47 sq mi; 1.2 km2) somewhere in Santa Monica near the Los Angeles Pacific Interurban Railroad line for Selig's Wild Animal Farm.[3] Big Otto managed Selig's Wild Animal Farm from 1912 to 1914.[4] In the mid-teens, Selig spent substantial funds acquiring and developing 32 acres (0.050 sq mi; 0.13 km2) of land in Lincoln Heights northeast of downtown Los Angeles, where he built a large elaborate zoo. The famous entrance gates were designed by an Italian sculptor named Romanelli.[5]

The public opening day of the zoo was June 20, 1915.[6] As of September 1915, the Selig Zoo housed over 700 animals including two giraffes (named Fritz and Leni[1]), nine lions, sacred cows from India, llamas from Peru, and an unidentified species of "temple monkey."[7] Elephant performer Toddles came to Selig from Big Otto by way of Ringling.[8] The head zookeeper was John Robinson.[7] The Selig Zoo held a five-year-old orangutan called Prince Chang.[9][10] He supposedly lived in a castle with a southern exposure and its own garden;[10] his enclosure was said to be electrically heated.[11] He appeared in a one-reel Selig film called The Orang-Outang.[12] Described as "enormous," Chang did not immediately take to the rigors of film production. He reportedly chased costar George Larkin around the studio while brandishing a cane, and wrecked two sets. Eventually, furniture made of cast iron bolted to the floor allowed production to continue.[13]

Two of the keepers at the Selig Zoo were brothers Clarence and Melvin Koontz, the latter of whom went on to a long career as an animal trainer.[14] A noted historian of American circuses and circus elephants, Chang Reynolds, worked at the Selig Zoo as a young man.[15]

In 1917 Selig sold the Edendale production facility to William Fox and moved Selig Polyscope to the zoo in East Los Angeles. Meanwhile, World War I cut severely into the substantial European revenues Selig Polyscope had been garnering, and the company shunned profitable movie industry trends, which had shifted towards dramatic (and more costly) full length feature films. Selig Polyscope became insolvent and ceased operations in 1918.

Movie studios rented animals and staged many shoots at the Selig zoo (sometimes later claiming they had been filmed in Africa). The first Tarzan movie (1918) was filmed there. In 1920 Louis B. Mayer rented his first studio space for Mayer Pictures at the site. Also in 1920 the Selig Zoo acquired a hyacinth macaw.[16]

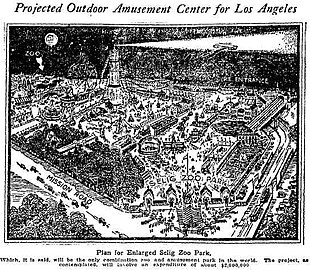

Selig planned to develop the property into a major tourist attraction, amusement park and popular resort named Selig Zoo Park with a Ferris wheel, carousels, mechanical rides, an enormous swimming pool with a sandy beach and a wave-making machine, hotel, theatre, cinema, restaurants and thousands of daily visitors (more than 30 years before Disneyland). Only a single carousel was built. Selig Polyscope's extensive collection of props and furnishings were auctioned off at the zoo in 1923. A young California condor captured in Ventura County was installed at the zoo in 1924.[17]

In 1925 a guidebook outlined the attractions for tourists:[18]

On entering, the visitor proceeds first to the Lion House, a low, quadrangular structure in Mission style, with the cages facing inward upon an arcade surrounding a central patio. There are 44 of these cages, containing lions, leopards and monkeys.

Proceeding S., we reach (on R.) a row of outdoor cages containing various birds and animals. Beyond are nine enclosures containing a large collection of pheasants, including some interesting hybrids. Oppo site are the Bear Dens, also a few smaller animals.

Further N. (on R.) are various birds. Opposite are the Ostrich pens. Behind the latter is the Elephant House.

Nearby is a circular Training Cage, where the process of training young lions and tigers for use in e may often be seen in the morning, and where Animal Acts are given Saturdays and Sundays at 3 o'clock .

Returning to entrance by E. path, we pass a group of cages containing a numerous assortment of Storks and Cranes.

The zoo was in operation until about 1935.[19][20] Selig finally sold out following a Los Angeles flood of 1938 during the Great Depression and what was then called Zoopark ceased to exist in 1940 after the cages and equipment were removed.[21] Some of the animals were donated to Los Angeles County, forming a substantial addition to Griffith Park Zoo. The property was used as a jalopy racetrack during the 1940s and early 1950s. In 1955 the site was described as "an inactive amusement park."[22]

The carousel survived on the site until 1976 when it was destroyed by fire. The former Selig Zoo's arched front gate with its lavish animal sculptures was a crumbling landmark in Lincoln Heights for many decades. By 2003 the sculptures were reportedly being restored for installation at the Los Angeles Zoo and in 2007 tennis courts were on the site.[23]

Gallery

-

Selig's Wild Animal Farm 1911ish to 1914ish somewhere in Santa Monica near a streetcar line

-

Animal collection highlights, 1915

-

Promotional drawing for the planned Selig Zoo Park in East LA, with light rail connections, cars speeding towards the entrance and long lines depicted at the gate. Only a single carousel was ever built and the site struggled as a lightly visited zoo for over a decade.

-

Asian elephant at the Selig Zoo, c. 1920

-

Selig Zoo and environs in Baist's Real Estate Atlas, 1921

See also

- Cawston Ostrich Farm – Los Angeles tourist attraction (1886–1935)

- Gay's Lion Farm – Tourist attraction in El Monte, California, United States (1925–1942)

- Catalina Bird Park – Aviary on Catalina Island, California (1926–1966)

- Feather Hill Zoo – Animal collection, Santa Barbara, California (1924–1930)

- Universal City Zoo – Animal collection in California (1913–1930)

- Jungleland USA – Defunct private zoo, animal training facility, and theme park

References

- ^ a b c Haenni, Sabine (2016). "Animal Empire: Thrill and Legitimation at William Selig's Zoo and Jungle Pictures". In Lawrence, Michael; Lury, Karen (eds.). The Zoo and Screen Media. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 87–110. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-53561-0_5. ISBN 978-1-137-54342-4. Retrieved 2023-02-15.

- ^ Slide, Anthony (1994). Early American Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8108-2722-6.

- ^ "Motography (Apr-Dec 1911) - Lantern". lantern.mediahist.org. Retrieved 2023-02-16.

- ^ "Maintaining a Wild Animal Jungle for Pictures, The Diamond S Farm, Motography (Jan-Dec 1912) - Lantern". lantern.mediahist.org. Retrieved 2023-02-16.

- ^ "Moving Picture World (Jul-Sep 1915) - Lantern". lantern.mediahist.org. Retrieved 2023-02-16.

- ^ The Movie Magazine: A National Motion Picture Magazine ... Movie Magazine Publishing Company, Incorporated. 1915. p. 24.

- ^ a b "Libyan Desert". The Los Angeles Times. September 5, 1915. p. 13. Retrieved 2023-02-15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Altoona Times 05 Jun 1913, page 12". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-02-16.

- ^ "Los Angeles Letter". Moving Picture World. Vol. 25, no. 7. August 14, 1915. p. 1144. Retrieved 2022-11-25 – via Media History Digital Library.

- ^ a b "Chang's Throne Totters". The San Francisco Call. Vol. 97, no. 154. June 26, 1915. p. 9. Retrieved 2022-11-25 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ Blaisdell, George (July 10, 1915). "Great Selig Enterprise". Moving Picture World. Vol. 25, no. 2. pp. 227–229. Retrieved 2022-11-25 – via Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "Selig display ad". Moving Picture World. Vol. 25, no. 6. August 7, 1915. p. 1095. Retrieved 2022-11-25 – via Media History Digital Library.

- ^ "A Wild Animal Film". The Bioscope. Vol. xxviii, no. 461. London. August 12, 1915. p. 655. Retrieved 2022-12-04 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Buck, Frank; Weld, Carol (1939). Animals are like that. New York: R.M. McBride and Co.

- ^ Reynolds, Chang (1966). Pioneer circuses of the West. Westernlore Press. OCLC 1352405.

- ^ The Golden West. C.E. Stokes. September 1920. p. 9.

- ^ Law, J. Eugene; Wyman, L. E.; Wright, W. S.; Bryant, Harold C. (July 1924). "From Field and Study". The Condor. 26 (4): 153–155. doi:10.2307/1363221. ISSN 1938-5129. JSTOR 1363221.

- ^ Rider, Fremont; Cooper, Frederic Taber (1925). Rider's California; a guide-book for travelers, with 28 maps and plans. New York: The Macmillan company: London, G. Allen & Unwin, ltd.

- ^ Locke, Michael (November 11, 2014). Silver Lake Chronicles: Exploring an Urban Oasis in Los Angeles. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62584-682-2.

- ^ Dangcil, Thomas; Dangcil, Tommy (2002). Hollywood, 1900-1950, in Vintage Postcards. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2073-5.

- ^ Sutherland, Henry. "Services Set Monday for Olga Celeste: OLGA CELESTE." Los Angeles Times, Sep 04, 1969, pp. 2-c1. ProQuest, magic number 156299655

- ^ "Los Angeles Times: Lionesses on archway of entrance to the Selig Zoo". UCLA Digital Library. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ^ Hall, Carla (May 14, 2009). "Zoo to display lion statues from early L.A. menagerie". LA Times. Retrieved 2018-06-21.