Structural analog

A structural analog, also known as a chemical analog or simply an analog, is a compound having a structure similar to that of another compound, but differing from it in respect to a certain component.[1][2][3]

It can differ in one or more atoms, functional groups, or substructures, which are replaced with other atoms, groups, or substructures. A structural analog can be imagined to be formed, at least theoretically, from the other compound. Structural analogs are often isoelectronic.

Despite a high chemical similarity, structural analogs are not necessarily functional analogs and can have very different physical, chemical, biochemical, or pharmacological properties.[4]

In drug discovery, either a large series of structural analogs of an initial lead compound are created and tested as part of a structure–activity relationship study[5] or a database is screened for structural analogs of a lead compound.[6]

Chemical analogues of illegal drugs are developed and sold in order to circumvent laws. Such substances are often called designer drugs. Because of this, the United States passed the Federal Analogue Act in 1986. This bill banned the production of any chemical analogue of a Schedule I or Schedule II substance that has substantially similar pharmacological effects, with the intent of human consumption.

Examples

-

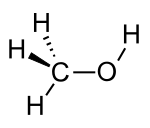

Silanol, a structural analog of methanol

-

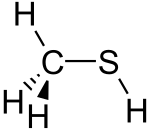

Methanethiol, a structural analog of methanol

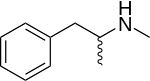

Neurotransmitter analog

A neurotransmitter analog is a structural analogue of a neurotransmitter, typically a drug. Some examples include:

See also

- Derivative (chemistry)

- Federal Analogue Act, a United States bill banning chemical analogues of illegal drugs

- Functional analog, compounds with similar physical, chemical, biochemical, or pharmacological properties

- Homolog, a compound of a series differing only by repeated units

- Transition state analog

References

- ^ Willett, Peter, Barnard, John M. and Downs, Geoffry M. (1998). "Chemical Similarity Searching" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences. 38 (6): 983–996. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.453.1788. doi:10.1021/ci9800211.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ A. M. Johnson; G. M. Maggiora (1990). Concepts and Applications of Molecular Similarity. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-62175-1.

- ^ N. Nikolova; J. Jaworska (2003). "Approaches to Measure Chemical Similarity - a Review". QSAR & Combinatorial Science. 22 (9–10): 1006–1026. doi:10.1002/qsar.200330831.

- ^ Martin, Yvonne C., Kofron, James L. and Traphagen, Linda M. (2002). "Do Structurally Similar Molecules Have Similar Biological Activity?". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 45 (19): 4350–4358. doi:10.1021/jm020155c. PMID 12213076.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schnecke, Volker & Boström, Jonas (2006). "Computational chemistry-driven decision making in lead generation". Drug Discovery Today. 11 (1–2): 43–50. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03703-7. PMID 16478690.

- ^ Rester, Ulrich (2008). "From virtuality to reality - Virtual screening in lead discovery and lead optimization: A medicinal chemistry perspective". Current Opinion in Drug Discovery & Development. 11 (4): 559–68. PMID 18600572.

External links

- Analoging in ChEMBL, DrugBank and the Connectivity Map – a free web-service for finding structural analogs in ChEMBL, DrugBank, and the Connectivity Map