Weltbühne trial

The Weltbühne-Prozess was a criminal procedure against critical media and journalists in the Weimar Republic. Among the accused were the editors of the weekly magazine Die Weltbühne and Carl von Ossietzky, plus the journalist Walter Kreiser. They were accused of treason and divulging military secrets. In November 1931, they were condemned by the 4. senat of the Reichsgericht in Leipzig to 18 months of imprisonment.

History

Treaty of Versailles

After the First World War the German Empire had to agree to a strong reduction of its military forces due to the Treaty of Versailles. Despite this signature the government and the Reichswehr tried systematically to undermine the provisions of the treaty.

Pacifist and anti-militarist circles in the Weimar Republic saw therefore on the behavior of the army a threat to the foreign policy consolidation of the German Reich and to inner peace.

Military Critical Press

Those media who were drawing attention to the grievances, were subjected to severe repression.

However, the Treaty of Versailles did not only limit the strength of the army. It prohibited in article 198 also expressly the set up of an own air force.

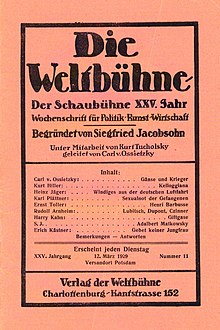

Against the described background, it is hardly surprising that in the Weltbühne under the pseudonym Heinz Hunter on March 12, 1929 published article "Windiges aus der deutschen Luftfahrt" arouse the displeasure of the army. In pacifist circles it was obvious that the army was apparently bypassing the Treaty of Versailles and ran to the clandestine construction of an air force.

The senior prosecutor launched an investigation for breach of the treason paragraphs of Penal Code and contrary to Clause 1, paragraph 2 of the Act against disclosure of military secrets (the so-called espionage Act of 3 June 1914 (Reichsgesetzblatt), 195).

Method

On August 1, 1929, finally, a criminal complaint was lodged. During the investigation, the editorial offices of the Weltbühne and the apartment of Ossietzky were searched. In August 1929 Ossietzky was also questioned about the case. On March 30, 1931, two years after the article had appeared, the indictment was made.

Legal actors

On the part of the prosecutor's office and the Supreme Court the Weltbühne had to do with lawyers who had already gained relevant awareness. Attorney Paul Jorns, was affected with the investigations of the murders of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg and had there covered tracks.[1] The head Alexander Baumgarten, had led in autumn 1930 the Ulm Reichswehrprozess where Adolf Hitler had given his Legalitätserklärungbut also announced that after the beginning of his government heads will roll.[2] The defense of the accused took over the renowned lawyers Max Alsberg, Kurt Rosenfeld, Alfred Apfel and Rudolf Olden.

Negotiation

According to the German laws, it was not allowed to the Weltbühne to report detailed about the process. Negotiations were immediately postponed because no representative of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had appeared. The hearing in camera finally took place on 17 and 19 November 1931. As witnesses for the prosecution acted Major Himer from the Ministry of the Reichswehr and Permanent Secretary Wegerdt from the Ministry of Transport. They confirmed that the information from the article was true and therefore should have been kept secret in the interests of defense.

The court rejected all 19 defense witnesses.

Judgment

The trial ended on 23 November with the conviction of the two accused for "crimes against the § 1 paragraph 2 of the law on disclosure of military secrets from June 3, 1914". The sentence was 18 months of imprisonment. In its reasoning, the court argued that the defendants after the specifying of the expert had really disseminated secret informations.

Political reactions

At the sentencing reacted von Ossietzky with sarcasm. "One and a half years of imprisonment? It is not so bad, because it is not far to the freedom in Germany here. The differences between incarcerated and non-incarcerated fade gradually".

- Quote:

I know that every journalist who is critically engaged in the Reichswehr, has to expect a treason process; … nevertheless, this time was made for a delightful variety: We left the room not as traitors but as spies.[3]

- Quote: The Reichsgericht has stamped me precautionary in a most unpleasant way. Treason and the treason of military secrets that is a very diffaming etikette, which is hard to live with.[4]

The verdict aroused at home and abroad for several reasons attention. The Weltbühne published in the editions of 1 December and 15 December 1931 numerous foreign press on the process. In Germany, many democratic politicians were shocked. Reichstag President Paul Löbe wrote: "I have rarely an opinion as such a bust felt not only in legal but also in political terms, as this."

Various organizations attempted to prevent Ossietzky actually had to play the sentence after the verdict. Ossietzky went on May 10, 1932 to prison Berlin-Tegel. His lawyers accompanied him. Quote:... I do not bow to the wrapped in red velvet majesty of the Supreme Court but remain as a passenger of a Prussian prison a vibrant demonstration against a highly-instance verdict, that appears politically tendentious in the matter and ample askew as legal work |.[5] Due to a Christmas amnesty for political prisoners Ossietzky was released early on December 22, 1932 after 227 days in prison.

Legal assessment

The process was certainly one of the sharpest attacks from Reichswehr and Justice against the critical press in the Weimar Republic. Moreover, it had become clear abroad that Germany did not intend to observe obviously important points of the Treaty of Versailles. Ossietzky conceded after his conviction that the Republic had at least safeguarded "the decorum of the legal process". During the so-called Spiegel scandal parallels were drawn from the press to the Weltbühne process. So published BGH - Senate President Heinrich Jagusch under the pseudonym "Judex" the highly acclaimed article "Is there a risk of new Ossietzky case?" .[6]

Retrial

In the 1980s, German lawyers attempted to achieve a retrial. Thus the judgment of 1931 should be revised. Rosalinde von Ossietzky-Palm, the only child of Carl von Ossietzky initiated as eligible on March 1, 1990 at the Berlin Supreme Court, the proceedings. The Court of Appeal declared a retrial inadmissible.

The Federal Court then declined to appeal against the decision of the Appeal Court. It held, in its decision of 3 December 1992:

Incorrect application of the law by itself is not a reason for reopening by the Code of Criminal Procedure. Every citizen owes to the consideration of the imperial court to his country a duty of loyalty to the effect that the effort could be realized according to the compliance with the existing laws....

.[7]

Sources

- Die Weltbühne. Vollständiger Nachdruck der Jahrgänge 1918–1933. Athenäum Verlag, Königstein/Ts. 1978, ISBN 3-7610-9301-2.

- Auswärtiges Amt: Geheimakten der Alten Rechtsabteilung, Rechtssache: Strafverfahren wegen Landesverrat gegen Schriftleiter Carl von Ossietzky, Bände 1 und 2 (unveröffentlicht)

- Kammergericht Berlin 1. Strafsenat, Beschluss vom 11. Juli 1991, Az: (1) 1 AR 356/90 (4/90), veröffentlicht in: Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (NJW). Beck, München/ Frankfurt M 1991, S. 2505–2507. ISSN 0341-1915

- BGH 3. Strafsenat, Beschluss vom 3. Dezember 1992, Az: StB 6/92, veröffentlicht in: BGHSt 39, S. 75–87.

- Carl von Ossietzky: Sämtliche Schriften. Herausgegeben von Bärbel Boldt u.a. Band VII: Briefe und Lebensdokumente. Reinbek 1994.

Secondary literature

- Hannover, Heinrich: Die Republik vor Gericht 1975–1995. Erinnerungen eines unbequemen Rechtsanwalts. Aufbau-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-7466-7032-2.

- Lang, Dieter: Staat, Recht und Justiz im Kommentar der Zeitschrift „Die Weltbühne“. P. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-631-30376-9.

- Suhr, Elke: Carl von Ossietzky. Eine Biographie. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Köln 1988, ISBN 3-462-01885-X.

Articles

- Jungfer, Gerhard, Müller, Ingo: 70 Jahre Weltbühnen-Urteil. In: Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (NJW). Beck, München/Frankfurt (Main) 2001, p. 3461–3465. ISSN 0341-1915

- Heiliger, Ivo (Pseudonym von Ingo Müller): Windiges aus der deutschen Rechtsprechung. In: Kritische Justiz (KJ). Nomos, Baden-Baden 1993, p. 194–198. ISSN 0023-4834

- Suhr, Elke: „Zu den Hintergründen des Weltbühnen'-Prozesses.“ In: Allein mit dem Wort. Erich Mühsam, Carl von Ossietzky, Kurt Tucholsky. Schriftstellerprozesse in der Weimarer Republik. Schriften der Erich-Mühsam-Gesellschaft. Heft 14, Lübeck 1997, ISBN 3-931079-17-1, p. 54–69.

References

- ^ Siehe: Ingo Müller: "Der berühmte Fall Ossietzky vom Jahr 1930 könnte sich jederzeit wiederholen …" In: Hans-Ernst Bötcher (Hrsg.): Recht Justiz Kritik, Festschrift für Richard Schmid. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1985, S. 297–326, hier p. 307.

- ^ Nach dem Republikschutzgesetz wäre dies strafbar gewesen. Vergleiche: Ingo Müller, S. 305.

- ^ Der Weltbühnen-Prozeß. In: Die Weltbühne. 1. Dezember 1931, S. 803.

- ^ Rechenschaft. In: Die Weltbühne. 10. Mai 1932, S. 691.

- ^ Rechenschaft. In: Die Weltbühne. 10. Mai 1932, S. 690.

- ^ "Droht ein neuer Ossietzky-Fall?", Der Spiegel, 13 September, no. 45, 1964

- ^ seinem Beschluss vom 3. Dezember 1992