No. 106 fuze

The number 106 fuze was the first British instantaneous percussion artillery fuze, first tested in action in late 1916 and deployed in volume in early 1917.

Background

Britain entered World War I with a policy of using shrapnel shells for its field guns (13-pounder and 18-pounder), intended to burst above head-height for anti-personnel use. British heavy artillery was expected to attack fortifications, requiring high-explosive shells to penetrate the target to some extent before exploding. Hence British artillery fuzes were optimised for these functions. Experiences of trench warfare on the Western front in 1914–1916 indicated that British artillery was unable to reliably destroy barbed-wire barricades, which required shells to explode instantaneously on contact with the wire or ground surface: British high-explosive shells would penetrate the ground before exploding, rendering them useless for destroying surface targets.

British No. 100 and later Nos. 101, 102 and 103 nose "graze" fuzes available in the field from August 1915 onwards[1] could explode a high-explosive shell very quickly on experiencing a major change in direction or velocity, but were not "instantaneous": there was still some delay in activation, and limited sensitivity: they could not detect contact with a frail object like barbed wire or soft ground surface. Hence they would penetrate objects or ground slightly before detonating, instead of on the ground surface as required for wire cutting.[2] These graze and impact fuzes continued to be used as intended for medium and heavy artillery high-explosive shells.

Up to and including the Battle of the Somme in 1916, British forces relied on shrapnel shells fired by 18-pounder field guns and spherical high-explosive bombs fired by 2-inch "plum-pudding" mortars for cutting barbed-wire defences. The disadvantage of shrapnel for this purpose was that it relied on extreme accuracy on setting the fuze timing to burst the shell close to the ground just in front of the wire: if the shell burst fractionally too short or too long it could not cut the wire, and also the spherical shrapnel balls were not of an optimal shape for cutting strands of wire. While the 2-inch mortar bombs cut wire effectively, their maximum range of 570 yards (520 m) limited their usefulness.

Design

Detonation mechanism

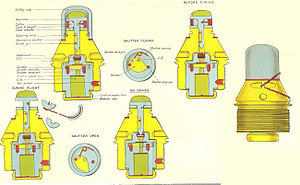

The number 106 fuze drew on French technology to provide a mechanism for reliably detonating a high-explosive shell instantaneously when the nose made physical contact with the slightest object like a strand of barbed wire or the ground surface. Hence it was a "direct action" rather than a "graze" fuze: simple deceleration or change of direction would not activate it, only direct physical contact between the hammer projecting from the nose and an external object. The basic mechanism was a steel hammer on the end of a spindle projecting forward from the nose of the fuze. The slightest movement inwards of this spindle caused the fuze to detonate and hence explode the shell before it penetrated the ground.

The steel hammer had a softer aluminium cap which absorbed the force of a glancing blow and prevented the spindle from bending or breaking, reducing the risk of misfire.

Arming and safety features

The first safety mechanism was a length of brass tape wrapped around the spindle between the fuze body and the hammer head, which prevented the spindle from moving inward. On firing, the hammer's inertia caused it to "setback" fractionally i.e. it resisted acceleration, and hence the accelerating fuze body forced the tape wrapped around the spindle against the underside of the hammer head, preventing the tape from unwinding. When acceleration ceased shortly after the shell left the gun barrel, the hammer and fuze body were travelling at the same speed and the hammer ceased to "set back", freeing the tape. The shell's rotation then caused a weight on the end of the tape to unwind the tape through centrifugal force, hence activating the fuze. Because of this, usage of this fuze in action was characterised by British troops in the front lines noticing the descending tapes detached from the fuzes as they travelled overhead towards the enemy lines.

After the tape detached during flight, the hammer was prevented from being forced inward by air resistance by a thin "shearing wire" passing through the hammer spindle, which was easily broken by the hammer encountering any physical resistance. The spindle was prevented from rotating relative to the fuze body in flight, and hence from snapping the shearing wire, by a guide pin passing through a cutout in the spindle.

Later versions (designated "E") incorporated an additional safety mechanism: an internal "shutter", also activated by rotation of the shell after firing, which closed the channel between the striker in the nose and the powder magazine in the base until it was clear of the gun which fired it. On firing, the shutter resisted acceleration ("setback") and the accelerating shell body pushed against it, preventing the shutter from moving. When acceleration ceased shortly after the shell left the gun barrel, the shutter ceased to "set back" and was free to spin outwards, activating the fuze.

Use in action

The fuze was first used experimentally in action in the later phases of the Battle of the Somme in late 1916, and entered service in early 1917.[3][4] From then onwards British forces had a reliable means of detonating high-explosive shells on the ground surface without merely digging holes as they had previously.

The chain of events necessary to allow the fuze to activate a shell were:

- Gunner removes the fuze's safety cap before loading

- Fuze accelerates violently on firing: the setback of the hammer prevents tape from unwinding while still in or near gun barrel

- Rifling in gun barrel causes the shell and hence fuze to spin rapidly

- Fuze exits gun barrel and ceases accelerating: the hammer ceases to setback, freeing up tape

- Fuze continues to spin between 1,300 and 1,700 revolutions per minute: safety shutter spins out ("E" models from 1917 onwards)

- Centrifugal force of weight on the end of the tape causes tape to unwind and detach from the hammer spindle

- Hammer encounters physical resistance (e.g. earth, rocks, wire) and decelerates, causing the momentum of the fuze body to snap the shearing wire and force the detonator onto the pointed end of the hammer spindle

- Detonator explodes, sending flame through the centre of the fuze body to C.E. (composition exploding) magazine in fuze base

- C.E. magazine detonates, sending flame into the shell nose

- Flame activates shell function, typically high-explosive or smoke

On the Western Front in 1917 and 1918, the No. 106 fuze was typically employed on high-explosive shells for cutting barbed wire, fired by 18-pounder field guns at short to medium range, and by Mk VII [5] and Mk XIX 6-inch field guns at long range. Its instantaneous action also made it useful for counter-battery fire: high-explosive shells fired by 60-pounder and six-inch field guns were targeted on enemy artillery, and by bursting above ground could cause maximum damage to enemy artillery, mountings and crew. It was also approved as the primary fuze for high-explosive shells for QF 4.5 inch howitzers from August 1916 onward.[4]

This fuze was also used to burst smoke shells.

There were many versions of the No. 106 and it remained in service in the form of its streamlined variant, the No. 115, until World War II.

Notes and references

- ^ Ministry of Munitions History 1922. Volume X The Supply of Munitions. Part V: Gun Ammunition Filling and Completing. Page 55.

- ^ "Compared with the French 75-mm H.E. which gave instantaneous effect on graze or burst very soon after ricochet, the British 18-pdr. H.E. shell that buried themselves on graze or burst from 10 to 15 ft. in the air after ricochet were comparatively valueless for wire-cutting". History of the Ministry of Munitions Volume X Part II, page 5, on the situation in early 1916.

- ^ "Authority was given to replace No. 100-type fuse by No. 106 in a large proportion of the medium shell and to adopt it in certain heavy natures between August and November 1916, but there was considerable delay before the new fuse was produced in large numbers". History of Ministry of Munitions, Volume X, Part V, page 48

- ^ a b History of Ministry of Munitions, Volume X, Part V, page 56

- ^ Farndale 1986 page 158, quoting War Office Artillery Notes No. 4 - Artillery in Offensive Operations, January 1917.

Bibliography

- General Sir Martin Farndale, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. Western Front 1914–18. London: Royal Artillery Institution, 1986. ISBN 1-870114-00-0

- Official History of the Ministry of Munitions, 1922. Volume X : The Supply of Munitions. Facsimile reprint by Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ISBN 1-84734-884-X

External links

War Office. "Chapperton Down Artillery School [film]". film.iwmcollections.org.uk. Imperial War Museum. 10:05:25:00. Retrieved 1 November 2013.