HMS Anne Galley

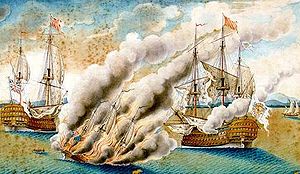

Anne Galley blowing up during the Battle of Toulon, 1744

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Anne Galley |

| Completed | 19 August 1739 at Deptford Dockyard |

| Acquired | 22 June 1739 |

| Commissioned | July 1739 |

| In service | 1739–1744 |

| Honours and awards |

|

| Fate | Destroyed off Toulon, 11 February 1744 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | 8-gun fire ship |

| Tons burthen | 30216⁄94 (bm) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 26 ft 8 in (8.1 m) |

| Depth of hold | 12 ft 3 in (3.7 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Complement | 55 |

| Armament | 8 × 6-pounder guns + 8 × ½-pounder swivel guns |

HMS Anne Galley was an 8-gun fire ship of the Royal Navy, launched in 1739 and in active service during the War of the Austrian Succession against Spain and France. Employed against the Spanish Fleet in 1744 off Toulon, she was destroyed while engaging the Spanish flagship Real Felipe.

Construction

Anne Galley was originally a commercial vessel owned by merchant George Stevens of Deptford. [1] As built, she was 97 ft 9 in (29.8 m) long with an 80 ft 0 in (24.4 m) keel, a beam of 26 ft 8 in (8.13 m), and measuring 30216⁄94 tonnes burthen.[2] She was two-decked, with a 12 ft 3 in (3.73 m) hold and four 6-pounder cannons located on each side of the lower deck.[3]

Stevens sold Anne Galley to the Royal Navy on 22 June 1739 for £1,209 and a further £87 for ship's stores.[3][a] On 3 July Anne Galley arrived at Deptford Dockyard for fitting out as a fire ship. Conversion to the role of fire ship involverd the construction of compartments in her hold for the storage of gunpowder and other combustible materials, and the cutting of a series of small chimneys into her deck to help ventilate fires set below. The eight lower deck gun ports had their hinges changed so they would fall open when their supporting ropes had burned through, further fanning any flames. Lastly, she received eight ½-pounder swivel guns along the upper deck railings for anti-personnel use.[3]

Naval service

Anne Galley was commissioned into the Navy in late July 1739 under Commander Richard Hughes. She was put to sea in August with a crew of 55 men, and assigned to Britain's Mediterranean fleet under the overall command of Vice-Admiral Nicholas Haddock. Britain was at war with Spain, and Anne Galley was sent to form part of the blockading squadron off the port of Cadiz.[5] She saw no active service during the year, although Commander Hughes was promoted to the rank of post-captain in October.[3] In 1741 she was with Haddock's fleet as it cruised between Cadiz and Toulon without engagement with the enemy at either port.[6]

Haddock was replaced in February 1742 by Admiral Richard Lestock, who determined to take a more aggressive position against the Spanish than had his predecessor. Command of Anne Galley also changed hands, passing to Commander Richard Hodsoll[3][b] For the next few months Anne Galley was deployed as a messenger to convey Lestock's orders to the captains of his larger ships.[7] She was also part of a small three-vessel squadron sent to the Bay of Ajaccio under Vice-Admiral Thomas Mathews to investigate reports that a single Spanish ship of the line was anchored there for repairs. On reaching the Bay the squadron, comprising Ipswich, Revenge and Anne Galley, encountered and overwhelmed the 70-gun Spanish warship Isidoro. The Spanish vessel was set on fire by her crew to avoid her being captured, and sank in the Bay. [8] This battle was Anne Galley's only engagement under Hodsoll's command, as he was replaced shortly afterward by Commander James Mackie.[3]

Battle of Toulon

France entered the war against Britain in 1743, leaving the Royal Navy's Mediterranean fleet at risk from the combined French and Spanish forces. On 9 February 1744 the fleet, comprising 38 vessels under Admiral Mathews, encountered a combined French and Spanish fleet of equivalent size off the port of Toulon. On the following morning both fleets formed lines of battle. Anne Galley was placed behind the centre of the British line but light winds and heavy swell kept the fleets apart throughout the day. At midday on the 11th, Admiral Mathews observed that the French and Spanish were seeking to depart without fighting, and gave the signal for immediate engagement.[9]

The subsequent battle centred around the Royal Navy flagship HMS Namur and the Spanish flagship Real Felipe. Both became disabled, with Real Felipe losing its masts and suffering around 500 casualties.[10] Seizing the opportunity, Mathews ordered Commander Mackie to bring Anne Galley forward to set the Spanish flagship ablaze.[11] Mathews had expected that the 70-gun HMS Essex would provide covering fire for Anne Galley but her captain, Richard Norris, refused to do so. When asked by his officers why he would not support the fire ship, Norris replied "We must not go down [to her aid]. If we do, we shall be sunk and tore to pieces."[12]

The Spanish observed Anne Galley's unsupported approach and opened fire with the remaining guns aboard Real Felipe as well as those of the 70-gun Hercules. The fire ship was repeatedly struck in the hull, and quantities of gunpowder were blown from the compartments across the decks and into the hold. To avoid casualties Commander Mackie ordered all but five of the crew to take to the boats, which were trailed on the far side of the ship to shelter them from enemy fire. Those still aboard busied themselves by opening the gun ports and scuttles and clearing the deck chimneys to ready the ship for being set alight. While they worked, Commander Mackie waited on deck holding the fuses that would light the explosives stored below.[11]

Sinking and aftermath

Despite these preparations, the fire ship was now so damaged that she seemed likely to sink before she reached the Real Felipe. A Spanish launch was also approaching Anne Galley with the intention of towing her away. To prevent this, Mackie went below and opened fire on the launch with his waist guns to no avail. Eventually, Real Felipe's gunfire hit Anne Galley's bows and ignited the loose gunpowder scattered about the fire ship's hold.[13][14][15] Other authors reported that the gunpowder was ignited by Mackie's own guns recoil.[11] Anne Galley promptly exploded, killing Mackie and all others aboard.[11][16] According to one observer she was "within her own length", or roughly 100 feet (30 m), from the disabled Real Felipe when she sank.[11][16]

Naval historian William Clowes has described Mackie's handling of Anne Galley as demonstrating "great ability and gallantry."[11] Despite this the fire ship did no real damage to the Spanish, with Real Felipe subsequently towed to safety by other vessels.[c] Those of Anne Galley's crew who had already taken to the boats before the explosion survived the fire ship's sinking and were able to make their way back to the British line.[11]

Captain Richard Norris of HMS Essex was court-martialed for cowardice following his failure to support Anne Galley, but the trial was abandoned in deference to his father, Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Norris. The younger Norris avoided a second court-martial for the same offence by resigning his Navy commission in February 1745.[18]

See also

Citations

Notes

References

- ^ Lyon (1993), p. 200.

- ^ Lyon 1993, p. 200

- ^ a b c d e f Winfield (2007), p. 345.

- ^ "Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to Present". MeasuringWorth. 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Clowes 1898, p.65

- ^ Clowes 1898, p.66

- ^ a b Clowes 1898, p. 81

- ^ Clowes 1898, p. 273

- ^ Clowes 1898, pp. 93–97

- ^ Clowes 1898, p. 99

- ^ a b c d e f g Clowes 1898, p. 100

- ^ Mackay 1965, p. 31

- ^ Barrow 1761, p. 135

- ^ Allen, Joseph (1842). "Admiral Matthews and Lestock". The United Service Magazine, Part 2. II: 328.

- ^ Lestock, Richard (1745). Vice-Admirall Lestock's Account of the Late Engagement Near Toulon: Between His Majesty's Fleet, and the Fleets of France and Spain; as Presented by Him the 12th of March 1744-5. Also, Letters to and from Admiral Lestock, ... With Notes, Volume 9. M. Cooper. p. 11.

- ^ a b Anon 1745, pp. 208–209

- ^ Burney 1807, p. 293

- ^ Mackay 1965, pp. 43–44

Bibliography

- Anonymous (1745). A Just, Genuine and Impartial History of the Memorable Sea-fight in the Mediterranean: Between the Combined Fleets of France and Spain, and the Royal Fleet of England, under the Commands of Two Admirals, Mathews and Lestock. London: R. Walker. OCLC 745056686.

- Barrow, John (1761). The Naval History of Great Britain. Vol IV. London, T. Lownds.

- Burney, William. The British Neptune, or A History of the Achievements of the Royal Navy from the Earliest Periods to the Present Time. London: Richard Phillips. OCLC 855518963.

- Clowes, W. L. (1898). The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 3. Sampson, Low, Marston & Co. OCLC 421848674.

- Lyon, David (1993). The Sailing Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy – Built, Purchased and Captured – 1688–1860. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 085177864X.

- Mackay, Ruddock F. (1965). Admiral Hawke. Clarendon Press. OCLC 460343756.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships of the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 9781844157006.