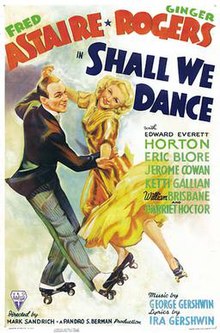

Shall We Dance (1937 film)

| Shall We Dance | |

|---|---|

theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mark Sandrich |

| Screenplay by | |

| Produced by | Pandro S. Berman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | David Abel Joseph F. Biroc |

| Edited by | William Hamilton |

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $991,000[1] |

| Box office | $2,168,000[1] |

Shall We Dance, released in 1937, is the seventh of the ten Astaire-Rogers musical comedy films. The idea for the film originated in the studio's desire to exploit the successful formula created by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart with their 1936 Broadway hit On Your Toes. The musical featured an American dancer getting involved with a touring Russian ballet company. In a major coup for RKO, Pandro Berman managed to attract the Gershwins – George Gershwin who wrote the symphonic underscore and Ira Gershwin the lyrics – to score this, their second Hollywood musical after Delicious in 1931.

Plot

Peter P. Peters (Fred Astaire), an American ballet dancer billed as "Petrov", dances for a ballet company in Paris owned by the bumbling Jeffrey Baird (Edward Everett Horton). Peters secretly wants to blend classical ballet with modern jazz dancing, and when he sees a photo of famous tap dancer Linda Keene (Ginger Rogers), he falls in love with her. He contrives to meet her, but she is less than impressed. They meet again on an ocean liner traveling back to New York, and Linda warms to Petrov. Unknown to them, a plot is launched as a publicity stunt "proving" that they are actually married. Outraged, Linda becomes engaged to the bumbling Jim Montgomery (William Brisbane), much to the chagrin of both Peters and Arthur Miller (Jerome Cowan), her manager, who secretly launches more fake publicity.

Peters and Keene, unable to squelch the rumor, decide to actually marry and then immediately get divorced. Linda begins to fall in love with her husband, but then discovers him with another woman, Lady Denise Tarrington (Ketti Gallian), and leaves before he can explain. Later, when she comes to his new show to personally serve him divorce papers, she sees him dancing with dozens of women, all wearing masks with her face on them: Peters has decided that if he cannot dance with Linda, he will dance with images of Linda. Seeing that he truly loves her, she happily joins him onstage.

Cast

|

|

Music

George Gershwin – who had become famous for blending jazz with classical forms – wrote each scene in a different style of dance music, and he composed one scene specifically for the ballerina Harriet Hoctor. Ira Gershwin seemed decidedly less excited by the idea; none of his lyrics make reference to the notion of blending different styles of dance (such as ballet and jazz), and Astaire was also not enthusiastic about the concept.

The score of Shall We Dance is probably the largest source of Gershwin orchestral works unavailable to the general public, at least since the advent of modern stereo recording techniques in the 1950s. The movie contains the only recordings of some of the instrumental pieces currently available to Gershwin aficionados (although not all the incidental music composed for the movie was used in the final cut.) Some of the cuts arranged and orchestrated by Gershwin include: "Dance of the Waves", "Waltz of the Red Balloons", "Graceful and Elegant", "Hoctor's Ballet" and "French Ballet Class". The instrumental track "Walking the Dog", however, has been frequently recorded and has been played from time to time on classical music radio stations.

Nathaniel Shilkret, musical director for the movie, hired Jimmy Dorsey and all or part of the Dorsey band as the nucleus of a fifty-piece studio orchestra including strings. Dorsey was in Hollywood at the time working the "Kraft Music Hall" radio show on NBC hosted by Bing Crosby. Dorsey is heard soloing on "Slap That Bass," "Walking the Dog" and "They All Laughed."

Gershwin was already suffering during the production of the motion picture from the brain tumor that was shortly to kill him, and Shilkret (as well as Robert Russell Bennett) contributed by assisting with orchestration on some of the numbers.

Musical numbers

Hermes Pan collaborated with Astaire on the choreography throughout and Harry Losee was brought in to help with the ballet finale. Gershwin modeled the score on the great ballets of the 19th century, but with obvious swing and jazz influences, as well as polytonalism. While Astaire made further attempts—notably in Ziegfeld Follies (1944/46), Yolanda and the Thief (1945) and Daddy Long Legs (1955)—it was his rival and friend Gene Kelly who would eventually succeed in creating a modern original dance style based on this concept. Some critics have attributed Astaire's discomfort with ballet (he briefly studied ballet in the 1920s) to his oft-expressed disdain for "inventing up to the arty".

- "Overture to Shall We Dance":was written by George Gershwin in 1937 as the introduction to his score for Shall We Dance. Performance time runs about four minutes. "The opening [number] is in Gershwin's best big-city style; propulsive, nervous, bustling with modern harmonies; it might have easily been developed into a full-scale composition except that time was growing short."[2]

- "French Ballet Class" written in the style of the galop.

- "Rehearsal Fragments": In a brief segment which seeks to motivate the film's core dance concept, Astaire illustrates the idea of combining "the technique of ballet with the warmth and passion of this other mood" by performing two ballet leaps, the second of which is followed by a tap barrage.

- "Rumba Sequence": Astaire watches a flip book showing a brief orchestral rumba danced by Ginger Rogers and Pete Theodore, choreographed by Hermes Pan; it is Rogers' only partnered dance without Astaire in the ten-film series of Astaire-Rogers musicals. The increasing complexity and chromaticism in Gershwin's music can be detected between music for this sequence and Gershwin's earlier effort at a rumba, the Cuban Overture, written five years earlier. Scored for chamber orchestra.

- "(I've Got) Beginner's Luck": A brief comic tap solo with cane where Astaire's rehearsing to a record of the number is cut short when the record gets stuck.

- "Waltz of the Red Balloons" written in the style of a valse joyeaux.

- "Slap That Bass": In a mixed race number unusual for its time, Astaire encounters a group of African-American musicians holding a jam session in a spotless, Art Deco-inspired ship's engine room. Dudley Dickerson introduces the first verse of the song whose chorus is then taken up by Astaire. The virtuoso tap solo which follows is the first substantial musical number in the picture, and can be seen as a successor to the "I'd Rather Lead A Band" solo from Follow the Fleet (1936)—which also took place aboard ship—this time introducing a vertical element to the predominantly linear choreography, some pointedly dismissive references to ballet positions, and a middle section similarly without musical accompaniment but now imaginatively supported by rhythmic engine noises. George Gershwin's color home-movie footage of Astaire rehearsing this number was discovered only in the 1990s.[3]

- "Dance of the Waves": written in the style of a barcarolle.

- "Walking the Dog": This was only published in 1960 as "Promenade" to accompany two pantomimic routines for Astaire and Rogers. This is the only part of the score besides Hoctor's Ballet to be published for performance in the concert hall, thus far. Scored for chamber orchestra. (Not all of the Walking the Dog sequence heard in the movie is in the published score, the ending of the scene features the themes following each other in a round (music).)

- "Beginner's Luck" (song): Astaire delivers this song to a non-committal Rogers, whose skepticism is echoed by a pack of howling dogs intervening at the close.

- "Graceful and Elegant": another waltz written by Gershwin, this one written in the style of the pas de deux (the first of two pas de deux in the score)

- "They All Laughed (at Christopher Columbus)": Ginger Rogers sings the introduction of Gershwin's now-classic song and is then joined by Astaire in a comic dance duet which begins with a ballet parody: Astaire in a mock-Russian accent invites Rogers to "tweeest" but after she pointedly fails to respond the pair revert to a tap routine which ends with Astaire lifting Rogers onto a piano.

- "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off": The genesis of the joke in Ira Gershwin's famous lyrics is uncertain: Ira has claimed the idea occurred to him in 1926 and remained unused. Astaire and Rogers sing alternate verses of this quickstep before embarking on a partnered comic tap dance on roller skates in a Central Park skating rink. Astaire uses the circular form of the rink to introduce a variation of the "oompah-trot" he and his sister Adele had made famous in vaudeville. In a further dig at ballet, the pair strike an arabesque pose just prior to toppling onto the grass.

- "They Can't Take That Away from Me": The Gershwins' famous foxtrot, a serene, nostalgic declaration of love;one of their most enduring creations and one of George's personal favorites—is introduced by Astaire. As with "The Way You Look Tonight" in Swing Time (1936), it was decided to reprise the melody as part of the film's dance finale. George Gershwin was unhappy about this, writing "They literally throw one or two songs away without any kind of plug". Astaire and Rogers said individually during their lives the song was one of their favourite personal songs, and they rescued it for The Barkleys of Broadway in (1949), his final reunion with Rogers, creating one of their most admired essays in romantic partnered dance, and it remains the only occasion on film when Astaire permitted himself to repeat a song he had performed in a previous film. George Gershwin died two months after the film's release, and he was posthumously nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Song for this song at the 1937 Academy Awards.

- "Hoctor's Ballet": The film's big production number begins with a ballet featuring a female chorus and ballet soloist Harriet Hoctor whose specialty was performing an elliptical backbend en pointe, a routine she had perfected during her vaudeville days and as a headline act with the Ziegfeld Follies. Astaire approaches and the pair perform a duet to a reprise of the music to "They Can't Take That Away From Me." This number runs directly into:

- "Shall We Dance/ Finale and Coda": After a brief routine for Astaire and a female chorus, each wearing Ginger masks, he departs and Hoctor returns to deliver two variations on her backbend routine. Astaire now returns in top hat, white tie and tails and delivers a rendition of the title song; urging his audience to "drop that long face/come on have your fling/why keep nursing the blues" and follows this with a zestful half-minute tap solo. Other musical nods are interwoven referencing the previous ballet sequences. Finally, Ginger arrives on stage, masked to blend in with the chorus whereupon Astaire unmasks her and they dance a brief final duet. This routine was referenced in the 1999 romantic comedy Simply Irresistible.

Production

While the film – the couple's most expensive to date – benefits from quality comedy specialists, opulent art direction by Carroll Clark under Van Nest Polglase's supervision, and a timeless score which introduces three classic Gershwin songs, the convoluted plot and the curious absence of a romantic partnered duet for Astaire and Rogers – a hallmark of their musicals since The Gay Divorcee (1934) – contributed to their least profitable picture to date.

Astaire was no stranger to the Gershwins, having headlined, with his sister Adele, two Gershwin Broadway shows: Lady Be Good! in 1924 and Funny Face in 1927. George Gershwin also accompanied the pair on piano in a set of recordings in 1926. Rogers first came to Hollywood's attention when she appeared in the Gershwins' 1930 stage musical Girl Crazy.[4]

Shall We Dance was named at the suggestion of Vincente Minnelli, who was a friend of the Gershwins. Minnelli originally suggested "Shall We Dance?" with a question mark, which disappeared at some point.

Reception

Shall We Dance earned $1,275,000 in the US and Canada and $893,000 elsewhere, resulting in a profit of $413,000, less than half the previous Astaire-Rogers film.[1] It was neither a box office nor a critical success, and was taken as an indication that the Astaire-Rogers pairing was slipping in its audience appeal.[5]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

Preservation status

On September 22, 2013 it was announced that a musicological critical edition of the full orchestral score of Shall We Dance will eventually be released. The Gershwin family, working in conjunction with the Library of Congress and the University of Michigan, are working to make scores available to the public that represent Gershwin's true intent.[7] The entire Gershwin project may take 30 to 40 years to complete, and it is unclear when Shall We Dance will be released.[8] Other than the sequences Hoctor's Ballet and Walking The Dog, it will be the first time the score has been published.[9]

In popular culture

- In the 2019 psychological thriller Joker, Arthur Fleck dances to the "Slap That Bass" segment playing on his TV in one scene.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Jewel, Richard. "RKO Film Grosses: 1931-1951". Historical Journal of Film Radio and Television, Vol 14 No 1, 1994, p. 56.

- ^ Jablonski 1998, p. 304.

- ^ "Gershwin films Astaire in Slap That Bass". Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Girl Crazy" at the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ McGee, Scott. "Articles: 'Shall We Dance' (1937)." TCM.com. Retrieved: April 1, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ^ Green, Zachary. "New, critical edition of George and Ira Gershwin’s works to be compiled." PBS NewsHour website, September 14, 2013. Retrieved: March 31, 2016.

- ^ Clague, Mark. "George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition" Musicology Now, September 30, 2013. Retrieved: March 31, 2016.

- ^ "The Gershwin Initiative: The Editions." University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance. Retrieved: March 31, 2016.

Bibliography

- Astaire, Fred. Steps in Time: An Autobiography. New York: Dey Street Books, 2008, First edition 1959. ISBN 978-0-0615-6756-8.

- Croce, Arlene. The Fred Astaire & Ginger Rogers Book. New York: Sunrise Books Publishers, 1972. ISBN 0-88365-099-1.

- Green, Stanley (1999) Hollywood Musicals Year by Year (2nd ed.), pub. Hal Leonard Corporation ISBN 0-634-00765-3 pages 68–69

- Jablonski, Edward. Gershwin: A New Critical Biography. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-3068-0847-0.

- Mueller, John E. Astaire Dancing: The Musical Films. New York: Alfred a Knopf Inc., 1985. ISBN 978-0-394-51654-7.

- Stockdale, Robert Lee. Jimmy Dorsey: A Study in Contrasts. Lanhalm, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8108-3536-3.

External links

- 1937 films

- 1930s musical comedy films

- 1930s romantic comedy films

- American dance films

- American musical comedy films

- American romantic comedy films

- American films

- American romantic musical films

- American black-and-white films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Mark Sandrich

- Musicals by George Gershwin

- RKO Pictures films

- George Gershwin in film

- 1930s dance films

- Publicity stunts in fiction

- 1937 comedy films