Drexel 4175

| Drexel 4175 | |

|---|---|

| New York Public Library for the Performing Arts | |

Drexel 4175 | |

| Also known as |

|

| Type | Commonplace book |

| Date | between 1620 and 1630 |

| Place of origin | England |

| Language(s) | English |

| Size | 25 leaves |

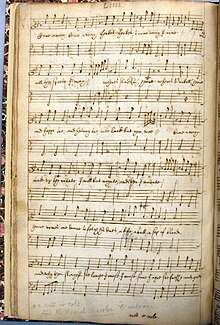

Drexel 4175, also known by an inscription on its cover, "Ann Twice, Her Book" or by the inscription on its first leaf, "Songs unto the violl and lute," is a music manuscript commonplace book. It is a noted source of songs from English Renaissance theatre,[1] considered to be "indispensable to the rounding-out of our picture of seventeenth-century English song."[2] Belonging to the New York Public Library, it forms part of the Music Division's Drexel Collection, located at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Following traditional library practice, its name is derived from its call number.[3]

Dating

John Stafford Smith suggested a date "about the year 1620" for the two songs ("Ist for a grace" and "You herralds of Mrs hart") he printed in his compilation Musica Antiqua.[4] Duckles mistakenly took this date to refer to the entire manuscript,[2] an assumption continued by Cutts.[1] In the introduction to the facsimile edition, Jorgens emended this misinterpretation, stating that scholars date the manuscript between 1620 an 1630.[5] She noted a problem posed by the song "Like to the damask rose": If the composer attribution of Henry Lawes is accepted, the appearance of this song in a manuscript from the 1620s pushes back the composer's reputation ten years before to most musicologists' understanding of his career. If the attribution is incorrect, then that casts doubt on the manuscript's many attributions.[6]

Provenance

Issues of provenance for Drexel 4175 begin with its cover. Its inscription "Ann Twice, Her Book" would indicate that one of the previous owners was Ann Twice, although no information has surfaced on who she was.[1][7] The first page has two inscriptions on it; the first is "Songs unto the violl and Lute." Beneath that is the note: "my Cosen Twice Leffte this Booke with me when shee went to Broisil which is to be returne to her AGhaine when she Come to Glost." Based on this note, musicologist Ian Spink concluded that Ann Twice lived in Gloucester around 1620 (the date based on John Stafford Smith's attributions).[8] Assuming the songs were copied for her use, Spink surmised that Twice must have been a good singer whose music master (the copyist of the manuscript) was "a man of taste." At some point she traveled to Bristol where she left the manuscript with her cousin, the writer of this inscription (whose name is unknown). The whereabouts of the manuscript are then unknown for nearly two centuries until Smith included selections in his collection Musica Antiqua.[9] In that publication Smith included a note referring to himself as the manuscript's owner.[10] Smith actually marked the manuscript to indicate those songs to be included in Musica Antiqua.

It is not known whether Edward Francis Rimbault purchased the volume directly from the sale of Smith's estate, but it eventually came into his possession.[11] Rimbault apparently lent the manuscript to Thomas Oliphant, cataloger of the British Museum (today the British Library). Oliphant's letter was affixed to front of manuscript stating that Oliphant made several "memorandums" (pencil markings in the manuscript). This letter is mentioned in the catalog of the Rimbault library auction, where it is listed as lot no. 1389 (the lot number can be seen penciled in on the first leaf).[12][10]

After Rimbault's death in 1876 followed by the auction of his estate in 1877, the manuscript was one of about 600 lots purchased by Philadelphia-born financier Joseph W. Drexel, who had already amassed a large music library. Upon Drexel's death, he bequeathed his music library to The Lenox Library. When the Lenox Library merged with the Astor Library to become the New York Public Library, the Drexel Collection became the basis for one of its founding units, the Music Division. Today, Drexel 4175 is part of the Drexel Collection in the Music Division, now located at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center.

Physical state

The manuscript measures 30.5 × 19 × 1 centimetre (12.01 × 7.48 × 0.39 in).

According to the manuscript's table of contents, there were originally 58 songs, including blank spaces intended for songs 59 and 60. The manuscript's numbering left out numbers 38 and 45. At some point a number of songs were removed so that, today, there are only 25 leaves containing 28 songs.[10][13] At least one song appears to have been removed since the time of Smith's ownership. "Rest awhile you cruell cares" (no. 39 of the table below) was noted by Smith and Oliphant, but is not present in the manuscript. Cutts questioned why it was removed, surmising the reason might have been for the song on its verso, "Haue you seen ye"?[14]

Due to its poor physical state, Drexel 4175 was rebound by conservators Carolyn Horton & Associates in 1981. The cover was separated and a new binding with marbled covers supplied.

Content

Of the 28 songs currently contained in the manuscript, six are from plays or masques (nos. 24, 29, 40, 43, 47, 52). Seven of the missing songs are also from dramatic works (nos. 2, 4, 5, 13, 19, 30 and 38). Seventeen of the songs have a simple bass accompaniment, ten have accompaniment notated in lute tablature (nos. 40–42, 50–51, 53–57) and one song lacks accompaniment (no. 58). Two songs are duplicates: No. 24 (no. xxiv) "Cupid is Venus only ioy" is repeated at no. 54 (no. lvi) and no. 40 (no. xli) "Deare doe not your faire beuty wronge" is repeated at no. 49 (li).

In its repetition at no. 49 (li), "Deare doe not your faire beuty wronge" is the only song to have a composer attribution, that of Robert Johnson.[15] Johnson is represented by several songs in the manuscript: "O let vs howle" (no. 4 from The Duchess of Malfi), "Tell mee dearest what is loue" (no. 43 from The Captain), "Haue you seene the bright lilly growe" (no. 47 from The Devil is an Ass), and "Heare yee ladyes yt" (formerly part of the manuscript as no. 19 from Valentinian). Cutts notes that all these plays were produced by King's Men, the repertory company to which Shakespeare belonged and for which Johnson wrote music from 1608-1617.[15]

Smith appears to have been the first to publish anything from the manuscript. He included six songs from it in his 1812 publication Musica Antiqua: "Come away, come away hecket" (no. 52), "Though your stragnes freet my hart" (no. 25), "Deare doe not your faire beuty wronge" (nos. 40 and 49), "Ist for a grace or ist for some mislike" (no. 20), "You herralds of Mrs hart" (no. 56), and "When I sit as iudge betweene vertue and loues princely dame" (no. 26).[9]

Smith apparently took particular interest in "Come away hecket" (no. 52), going as far as to note that it was the music used in Thomas Middleton's play The Witch.[16] Cutts took great interest in the song, surmising that the song was probably in the possession of a member of the King's Men,[17] which is how it is quoted in the 1623 folio of Shakespeare's Macbeth. Comparing it to another "witch" song known to have been composed by Johnson, "Come away ye lady gay", Cutts feels that similar attributes of compositional technique and verbal rhythm suggest that Johnson also composed "Come away hecket."[18] Cutts used this evidence to underscore his theory that this song was an inspiration for the witches' scene in Macbeth.

Based on the titles of the missing songs provided in the table of contents, Cutts was able to make observations (sometimes extensive) on the content, when possible noting their existence in different contemporaneous manuscript collections.[19]

Of those who have studied the manuscript, none have made more than fleeting comments on the manuscript's non-musical content, consisting of recipes and poems.[6] Curiously, the recipes have been written upside down in comparison to the remainder of the book. Duckles specifically mentioned recipes for carpe pye, pigeon pye, marrow pudding and French bread.[2]

List of contents

This list is based on the table of contents and includes numbering from Jorgens[20] and the numbering used in the manuscript. Those songs not in the manuscript are indicated in the column as "Not in ms." with a row color of silver. Most of the attributions and remarks were provided by Cutts.[19]

| Jorgens | In manuscript | Title | In ms.? | Attributions | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I | You meaner bewties | Not in ms. | lyric by Henry Wotton | probably written about 1612-1613; first printed in Michael East's "The Sixt Set of Bookes" (1624)[21] |

| 2 | ii | Was euer wight | Not in ms. | lyric by Thomas Edwards | from Cephalus and Procris |

| 3 | iii | He downe d: d: | Not in ms. | a frequent refrain of Elizabethan songs and later[21] | |

| 4 | iiii | O let vs howle | Not in ms. | music ascribed to Robert Johnson; text by John Webster | From The Duchess of Malfi; another copy at no. 42 [21] |

| 5 | v | I was not weary where | Not in ms. | music ascribed to Nicholas Lanier; text by Ben Jonson | The epilogue to The Vision of Delight (1617) |

| 6 | vi | Sweete staye ://: | Not in ms. | Lyric ascribed to John Donne | Ascriptions based on publications of Dowland (1612) and Gibbons (1612) |

| 7 | vii | Mrs since you soe much | Not in ms. | lyric by Thomas Campion | Published in Philip Rosseter's A Booke of Ayres (1601) |

| 8 | viii | Cloris sighte | Not in ms. | music by Richard Balls (died in 1622); lyric attributed by John Donne to William Herbert, 3rd earl of Pembroke | in Poems (1678); a song with this title appears in New Ayres and Dialogues (1678); another copy at lii |

| 9 | ix | Like hermit poore | Not in ms. | translation of a sonnet by Philippe Desportes possibly by Walter Raleigh[22] | |

| 10 | x | Some kinde muse | Not in ms. | ||

| 11 | xi | A thousand kisses | Not in ms. | Most likely the same as "A thousand kisses wynns my hearte from mee" in British Library manuscript Add. 24665[23] | |

| 12 | xii | As life what is soe | Not in ms. | Found by Norman Ault in a British Library manuscript dated 1624 | |

| 13 | xiii | In Sherwoode | Not in ms. | possibly the lyric with the same title in A Musicall Dreame (1609) by Robert Jones | |

| 14 | xiiii | Thou sents to me | Not in ms. | lyric by Robert Aytoun | |

| 15 | xv | Shall I weepe | Not in ms. | ||

| 16 | xvi | Goe thy wayes since | Not in ms. | The text of stanzas 2-5 present without music; begins “Yet I will not curse those eyes” | |

| 17 | xvii | Milla the glorie of whose bewteous rayes | A variant of the "May and Time" riddle from Thomas Morley's The First Booke of Ayres, or little short Songs (1600) | ||

| 18 | xviii | Thus sange Orpheus | Not in ms. | Possibly identical to the version published in Walter Porter's Madrigales and Ayres first published in 1632 but likely composed before that | |

| 19 | xix | Heare yee ladyes yt | Not in ms. | text by John Fletcher; music by Robert Johnson | From the play Valentinian |

| 20 | xx | Ist for a grace or ist for some mislike | lyric by John Harington | First published in 1633 but found in earlier manuscripts | |

| 21 | xxi | Why should pasion leade mee blinde | The lyric was first published in 1660 but dating earlier | ||

| 22 | xxii | The say Dymph, Gaho, followes to the shadie woods | |||

| 23 | xxiii | Fi, fi, fi, fi, what doe you meane by this? | |||

| 24 | xxiiii | Cupid is Venus only ioy | text by Thomas Middleton | from A Chaste Maid in Cheapside; another copy at lvi | |

| 25 | xxv | Though your stragnes freet my hart | music by Robert Jones? Thomas Campion? | ||

| 26 | xxvi | When I sit as iudge betweene vertue and loues princely dame | |||

| 27 | xxvii | When sorrowe singes a litle a litles enough | |||

| 28 | xxviii | Wrong not deare Empress of my hearte | Lyric attributed to Walter Raleigh | ||

| 29 | xxix | What is you lacke, what would you buy | from The Masque of Mountebankes (1618); this version incomplete | ||

| 30 | xxx | Orpheus I am come | Not in ms. | lyric by John Fletcher | From The Mad Lover |

| 31 | xxxi | Sorrow: sorrow stay | Not in ms. | Possibly the same as the one composed by John Dowland | |

| 32 | xxxii | Eyes looke of [off] | Not in ms. | A song with this title appears in other contemporaneous manuscripts | |

| 33 | xxxiii | Let her giue her hand | Not in ms. | A song with this title appears in other contemporaneous manuscripts | |

| 34 | xxxiiii | Fares [Fairies?] be hence | Not in ms. | ||

| 35 | xxxv | Come pretty wanton | Not in ms. | A song with this title appears in other contemporaneous manuscripts | |

| "Haue you seene [lute]"; entry is crossed out | |||||

| 36 | xxxvi | Shall I then relent, or: | Not in ms. | ||

| 37 | xxxvii | Sweetest loue, I doe not goe | Not in ms. | Text possibly by John Donne | |

| xxxviii | No song xxxviii in list | ||||

| 38 | xxxix | Haue you seense ye [lute] | Not in ms. | lyric by Ben Jonson | From the play The Devil is an Ass (1616); another copy at 47 (xlix) |

| 39 | xl | Rest awile you cruell cares | music by [John Dowland] | Published in The First Booke of Songes or Ayres (1597) | |

| 40 | xli | Deare doe not your faire beuty wronge | music by Robert Johnson, text by Thomas May | from the play The Old Couple (1636); lute tablature; another copy at li; the only song in the collection with authorial ascription | |

| 41 | xlii | O let vs howle some heauy note | music by Robert Johnson | lute tablature | |

| 42 | xliii | Like to the damaske rose you see | music by Henry Lawes | lute tablature | |

| 43 | xliiii | Tell mee dearest what is loue | music by Robert Johnson; text by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher | From the play The Captain | |

| xlv | No song xlv | ||||

| 44 | xlvi | Downe [downe] afflicted soule and paye thy due | Appears in contemporaneous manuscripts | ||

| 45 | xlvii | Sit and despayre | Not in ms. | Appears in contemporaneous manuscripts | |

| 46 | xlviii | How now sheapheard | Not in ms. | Appears in contemporaneous manuscripts | |

| 47 | xlix | Haue you seene the bright lilly growe | lyric by Ben Jonson | From the play The Devil is an Ass (1616); | |

| 48 | l | Venus went wandringe Adonis to finde | Appears in contemporaneous manuscripts | ||

| 49 | li | Deare doe not your faire bewty wrounge | music by Robert Johnson | another copy at 40 | |

| 50 | lii | Cloris sighte, and sange, and wepte | music by Alphonso Bales? | lute tablature; another copy at 8 | |

| 51 | liii | Come sorrowe sitt downe by this tree | lute tablature | ||

| 52 | liiii | Come away, Come away hecket | lyric by Thomas Middleton; music attributed to Robert Johnson[15] | From the play The Witch | |

| 53 | lv | O where am I, what may I thinke | lyric attributed to Samuel Brooke | lute tablature | |

| 54 | lvi | Cupid is Venus only ioy | lute tablature; another copy at 24 | ||

| 55 | lvii | Wherefore peepst thou enuious day? | music by John Wilson, lyric by John Donne | lute tablature | |

| 56 | lviii | You herralds of Mrs hart | Music attributed to John Wilson by Rimbault (who wrote in the manuscript); lute tablature | ||

| 57 | lix | Get you hence for I must goe | lute tablature | ||

| 58 | Ile tell you how the rose grewe redd | Text by William Strode | lacking accompaniment; unnumbered |

Bibliography

- Catalogue of the valuable library of the late Edward Francis Rimbault, comprising an extensive and rare collection of ancient music, printed and in manuscript...which will be sold by auction, by Messrs. Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge ... on Tuesday, the 31st of July, 1877, and five following days, London: Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, 1877, p. 92

- Cutts, John P. (1956), "The Original Music to Middleton's The Witch", Shakespeare Quarterly, 7 (2): 203–209, doi:10.2307/2866439

- Cutts, John P. (1962), "'Songs Vnto the Violl and Lute': Drexel Ms. 4175", Musica Disciplina, 16: 73–92

- Duckles, Vincent H. (Jan 1953), "Jacobean Theatre Songs", Music & Letters, 34 (1): 88–89, doi:10.1093/ml/xxxiv.1.88

- Henze, Catherine A. (Spring 2000), "How Music Matters: Some Songs of Robert Johnson in the Plays of Beaumont and Fletcher", Comparative Drama, 34 (1): 1–32, doi:10.1353/cdr.2000.0026

- Jorgens, Elise Bickford (1987), Miscellaneous Manuscripts, English song, 1600-1675: Facsimiles of Twenty-Six Manuscripts and an Edition of the Texts, vol. 11, ISBN 9780824082413

- Mateer, David (1999), "Hugh Davis's Commonplace Book: A New Source of Seventeenth-Century Song", Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, 32: 63–87, doi:10.1080/14723808.1999.10540984

- Smith, John Stafford (1812), Musica Antiqua: a Selection of Music of This and Other Countries From the Commencement of the Twelfth to the Beginning of the Eighteenth Century, London: Preston

- Spink, Ian (May 1962), "Ann Twice, Her Booke", Musical Times, 103 (No. 1431): 316, doi:10.2307/948800

{{citation}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - Walls, Peter (July 1984), "'Music and Sweet Poetry'? Verse for English Lute Song and Continuo Song", Music & Letters, 65 (3): 237–254, doi:10.1093/ml/65.3.237

Facsimile

Jorgens, Elise Bickford, ed. (1987). Miscellaneous Manuscripts. English song, 1600-1675: Facsimiles of Twenty-Six Manuscripts and an Edition of the Texts. Vol. 11. New York: Garland. ISBN 9780824082413.

Notes

- ^ a b c Cutts 1962, p. 73.

- ^ a b c Duckles 1953, p. 89.

- ^ Resource Description and Access, rule 6.2.2.7, option c (access by subscription).

- ^ Smith 1812, p. 62-63.

- ^ Jorgens 1987, p. vii. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFJorgens1987 (help)

- ^ a b Jorgens 1987, p. viii. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFJorgens1987 (help)

- ^ The database "England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538–1975" on Ancestry.com lists an Ann Twice who was christened June 3, 1698 at Cantebury, and whose mother was also named Ann Twice.

- ^ Spink 1962, p. 316.

- ^ a b Smith 1812.

- ^ a b c Cutts 1962, p. 74.

- ^ Several items from Smith's collection, including some of Smith's manuscript compilations, made their way into Rimbault's library and now are part of the New York Public Library's Drexel Collection.

- ^ Catalogue 1877, p. 92.

- ^ Duckles mistakenly counted 27.

- ^ Cutts 1962, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Cutts 1956, p. 206.

- ^ Smith 1812, p. 48.

- ^ Cutts 1956, p. 203-209.

- ^ Cutts 1956, p. 206-207.

- ^ a b Cutts 1962.

- ^ Jorgens 1987. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFJorgens1987 (help)

- ^ a b c Cutts 1962, p. 80.

- ^ Cutts 1962, p. 82.

- ^ David Greer, "An Early Setting of Lines from 'Venus and Adonis'," Music & Letters vol. 45, No. 2 (Apr., 1964), p. 127.