Catena (linguistics)

A major contributor to this article appears to have a close connection with its subject. (June 2020) |

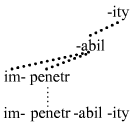

In linguistics, the catena (English pronunciation: /kəˈtiːnə/, plural catenas or catenae; from Latin for "chain")[1] is a unit of syntax and morphology, closely associated with dependency grammars. It is a more flexible and inclusive unit than the constituent and may therefore be better suited than the constituent to serve as the fundamental unit of syntactic and morphosyntactic analysis.[2]

The catena has served as the basis for the analysis of a number of phenomena of syntax, such as idiosyncratic meaning, ellipsis mechanisms (e.g. gapping, stripping, VP-ellipsis, pseudogapping, sluicing, answer ellipsis, comparative deletion), predicate-argument structures, and discontinuities (topicalization, wh-fronting, scrambling, extraposition, etc.).[3] The catena concept has also been taken as the basis for a theory of morphosyntax, i.e. for the extension of dependencies into words; dependencies are acknowledged between the morphs that constitute words.[4]

While the catena concept has been applied mainly to the syntax of English, other works are also demonstrating its applicability to the syntax and morphology of other languages.[5]

Descriptions and definitions

Two descriptions and two definitions of the catena unit are now given.

- Catena (everyday description)

- Any single word or any combination of words that are linked together by dependencies.

- Catena (graph-theoretic description)

- In terms of graph theory, any syntactic tree or connected subgraph of a tree is a catena. Any individual element (word or morph) or combination of elements linked together in the vertical dimension is a catena. Sentence structure is conceived of as existing in two dimensions. Combinations organized along the horizontal dimension (in terms of precedence) are called strings, whereas combinations organized along the vertical dimension (in terms of dominance) are catenae. In terms of a cartesian coordinate system, strings exist along the x-axis, and catenae along the y-axis.

- Catena (informal graph-theoretic definition)

- Any single word or any combination of words that are continuous in the vertical dimension, that is, with respect to dominance (y-axis).[6]

- Catena (formal graph-theoretic definition)

- Given a dependency tree T, a catena is a set S of nodes in T such that there is one and only one member of S that is not immediately dominated by any other member of S.[7]

Four units

An understanding of the catena is established by distinguishing between the catena and other, similarly defined units. There are four units (including the catena) that are pertinent in this regard: string, catena, component, and constituent. The informal definition of the catena is repeated for easy comparison with the definitions of the other three units:[8]

- String

- Any single element or combination of elements that are continuous in the horizontal dimension (x-axis)

- Catena

- Any single element or combination of elements that are continuous in the vertical dimension (y-axis)

- Component

- Any single element or combination of elements that form both a string and a catena

- Constituent

- A component that is complete

A component is complete if it includes all the elements that its root node dominates. The string and catena complement each other in an obvious way, and the definition of the constituent is essentially the same as one finds in most theories of syntax, where a constituent is understood to consist of any node plus all the nodes that that node dominates. These definitions will now be illustrated with the help of the following dependency tree. The capital letters serve to abbreviate the words:

All of the distinct strings, catenae, components, and constituents in this tree are listed here:[9]

- Distinct strings

- A, B, C, D, E, F, AB, BC, CD, DE, EF, ABC, BCD, CDE, DEF, ABCD, BCDE, CDEF, ABCDE, BCDEF, and ABCDEF

- Distinct catenae

- A, B, C, D, E, F, AB, BC, CF, DF, EF, ABC, BCF, CDF, CEF, DEF, ABCF, BCDF, BCEF, CDEF, ABCDF, ABCEF, BCDEF, and ABCDEF.

- Distinct components

- A, B, C, D, E, F, AB, BC, EF, ABC, DEF, CDEF, BCDEF, and ABCDEF

- Distinct constituents

- A, D, E, AB, DEF, ABCDEF

Noteworthy is the fact that the tree contains 39 distinct word combinations that are not catenae, e.g. AC, BD, CE, BCE, ADF, ABEF, ABDEF, etc. Observe as well that there are a mere six constituents, but 24 catenae. There are therefore four times more catenae in the tree than there are constituents. The inclusivity and flexibility of the catena unit becomes apparent. The following Venn diagram provides an overview of how the four units relate to each other:

History

The catena concept has been present in linguistics for a few decades. In the 1970s, the German dependency grammarian Jürgen Kunze called the unit a Teilbaum 'subtree'.[10] In the early 1990s, the psycholinguists Martin Pickering and Guy Barry acknowledged the catena unit, calling it a dependency constituent.[11] However, the catena concept did not generate much interest among linguists until William O'Grady observed in his 1998 article that the words that form idioms are stored as catenae in the lexicon.[12] O'Grady called the relevant syntactic unit a chain, however, not a catena. The term catena was introduced later by Timothy Osborne and colleagues as a means of avoiding confusion with the preexisting chain concept of Minimalist theory.[13] Since that time, the catena concept has been developed beyond O'Grady's analysis of idioms to serve as the basis for the analysis of a number central phenomena in the syntax of natural languages (e.g. ellipsis and predicate-argument structures).[14]

Idiosyncratic language

Idiosyncratic language of all sorts can be captured in terms of catenae. When meaning is constructed in such a manner that does not allow one to acknowledge meaning chunks as constituents, the catena is involved. The meaning bearing units are catenae, not constituents. This situation is illustrated here in terms of various collocations and proper idioms.

Some collocations

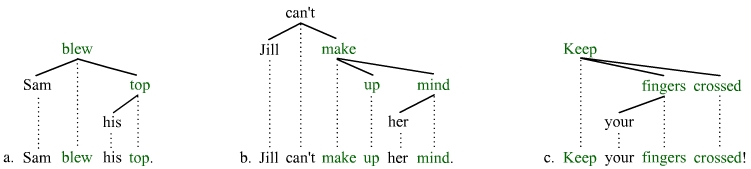

Simple collocations (i.e. the co-occurrence of certain words) demonstrate well the catena concept. The idiosyncratic nature of particle verb collocations provide the first group of examples: take after, take in, take on, take over, take up, etc. In its purest form, the verb take means 'seize, grab, possess'. In these collocations with the various particles, however, the meaning of take shifts significantly each time depending on the particle. The particle and take convey a distinct meaning together, whereby this distinct meaning cannot be understood as a straightforward combination of the meaning of take alone and the meaning of the preposition alone. In such cases, one says that the meaning is non-compositional. Non-compositional meaning can be captured in terms of catenae. The word combinations that assume non-compositional meaning form catenae (but not constituents):

Both the a- and b-sentences show that while the verb and its particle do not form a constituent, they do form a catena each time. The contrast in word order across the sentences of each pair illustrates what is known as shifting. Shifting occurs to accommodate the relative weight of the constituents involved. Heavy constituents prefer to appear to the right of lighter sister constituents. The shifting does not change the fact that the verb and particle form a catena each time, even when they do not form a string.

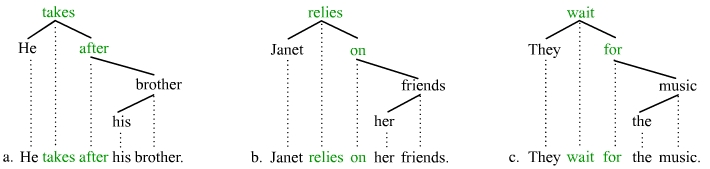

Numerous verb-preposition combinations are idiosyncratic collocations insofar as the choice of preposition is strongly restricted by the verb, e.g. account for, count on, fill out, rely on, take after, wait for, etc. The meaning of many of these combinations is also non-compositional, as with the particle verbs. And also as with the particle verbs, the combinations form catenae (but not constituents) in simple declarative sentences:

The verb and the preposition that it demands form a single meaning-bearing unit, whereby this unit is a catena. These meaning-bearing units can thus be stored as catenae in the mental lexicon of speakers. As catenae, they are concrete units of syntax.

The final type of collocations produced here to illustrate catenae is the complex preposition, e.g. because of, due to, inside of, in spite of, out of, outside of, etc. The intonation pattern for these prepositions suggests that orthographic conventions are correct in writing them as two (or more) words. This situation, however, might be viewed as a problem, since it is not clear that the two words each time can be viewed as forming a constituent. In this regard, they do of course qualify as a catena, e.g.

The collocations illustrated in this section have focused mainly on prepositions and particles and they are therefore just a small selection of meaning-bearing collocations. They are, however, quite suggestive. It seems likely that all meaning-bearing collocations are stored as catenae in the mental lexicon of language users.

Proper idioms

Full idioms are the canonical cases of non-compositional meaning. The fixed words of idioms do not bear their productive meaning, e.g. take it on the chin. Someone who "takes it on the chin" does not actually experience any physical contact to their chin, which means that chin does not have its normal productive meaning and must hence be part of a greater collocation. This greater collocation is the idiom, which consists of five words in this case. While the idiom take it on the chin can be stored as a VP constituent (and is therefore not a problem for constituent-based theories), there are many idioms that clearly cannot be stored as constituents. These idioms are a problem for constituent-based theories precisely because they do not qualify as constituents. However, they do of course qualify as catenae. The discussion here focuses on these idioms since they illustrate particularly well the value of the catena concept.

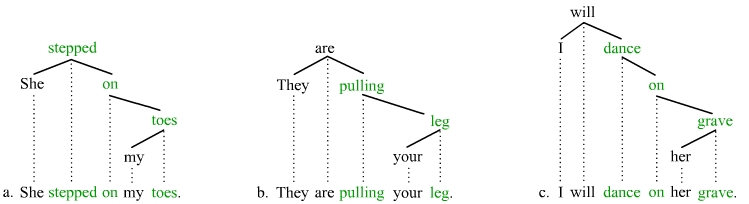

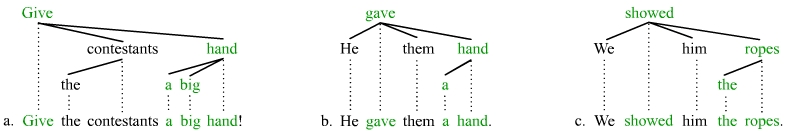

Many idioms in English consist of a verb and a noun (and more), whereby the noun takes a possessor that co-indexed with the subject and will thus vary with subject. These idioms are stored as catenae but clearly not as constituents, e.g.

Similar idioms have a possessor that is freer insofar as it is not necessarily co-indexed with the subject. These idioms are also stored as catenae (but not as constituents),[15] e.g.

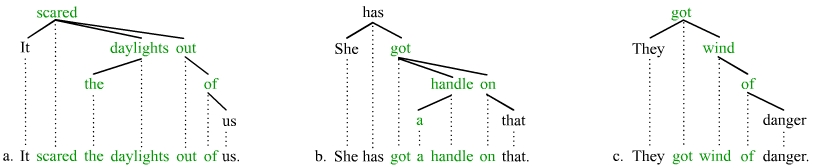

The following idioms include the verb, and object, and at least one preposition. It should again be obvious that the fixed words of the idioms can in no way be viewed as forming constituents:

The following idioms include the verb and the prepositional phrase at the same time that the object is free:

And the following idioms involving a ditransitive verb include the second object at the same time that the first object is free:

Certainly sayings are also idiomatic. When an adverb (or some other adjunct) appears in a saying, it is not part of the saying. Nevertheless, the words of the saying still form a catena:

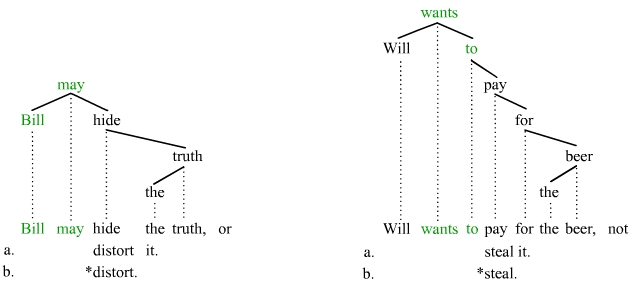

Ellipsis

Ellipsis mechanisms (gapping, stripping, VP-ellipsis, pseudogapping, answer fragments, sluicing, comparative deletion) are eliding catenae, whereby many of these catenae are non-constituents.[16] The following examples illustrate gapping:[17]

The a-clauses are acceptable instances of gapping; the gapped material corresponds to the catena in green. The b-clauses are failed attempts at gapping; they fail because the gapped material does not correspond to a catena. The following examples illustrate stripping. Many linguists see stripping as a particular manifestation of gapping where just a single remnant remains in the gapped/stripped clause:[18]

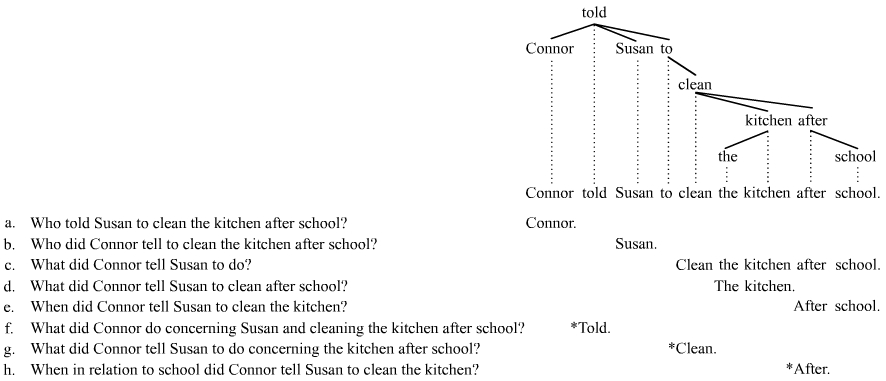

The a-clauses are acceptable instances of stripping, in part because the stripped material corresponds to a catena (in green). The b-clauses again fail; they fail because the stripped material does not qualify as a catena. The following examples illustrate answer ellipsis:[19]

In each of the acceptable answer fragments (a–e), the elided material corresponds to a catena. In contrast, the elided material corresponds to a non-catena in each of the unacceptable answer fragments (f–h).

Predicate-argument structures

The catena unit is suited to an understanding of predicates and their arguments.[20] -- a predicate is a property that is assigned to an argument or as a relationship that is established between arguments. A given predicate appears in sentence structure as a catena, and so do its arguments. A standard matrix predicate in a sentence consists of a content verb and potentially one or more auxiliary verbs. The next examples illustrate how predicates and their arguments are manifest in synonymous sentences across languages:

The words in green are the main predicate and those in red are that predicate's arguments. The single-word predicate said in the English sentence on the left corresponds to the two-word predicate hat gesagt in German. Each predicate shown and each of its arguments shown is a catena.

The next example is similar, but this time a French sentence is used to make the point:

The matrix predicates are again in green, and their arguments in red. The arrow dependency edge marks an adjunct -- this convention was not employed in the examples further above. In this case, the main predicate in English consists of two words corresponding to one word in French.

The next examples delivers a sense of the manner in which the main sentence predicate remains a catena as the number of auxiliary verbs increases:

Sentence (a) contains one auxiliary verb, sentence (b) two, and sentence (c) three. The appearance of these auxiliary verbs adds functional information to the core content provided by the content verb revised. As each additional auxiliary verb is added, the predicate grows, the predicate catena gaining links.

When assessing the approach to predicate-argument structures in terms of catenae, it is important to keep in mind that the constituent unit of phrase structure grammar is much less helpful in characterizing the actual word combinations that qualify as predicates and their arguments. This fact should be evident from the examples here, where the word combinations in green would not qualify as constituents in phrase structure grammars.

See also

Notes

- ^ "catena". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d.

- ^ Osborne et al. (2012) develop this claim at length, namely that the catena unit should be regarded as the fundamental unit of syntax rather than the constituent.

- ^ Osborne (2019) discusses many of these mechanisms of syntax on a basis of the catena unit.

- ^ Two articles that acknowledge morph catenae, i.e. catenae the links of which are morphs (as opposed to complete words) are Groß and Osborne (2013) and Groß (2014). The former article, which is in German, demonstrates that constructions often consist of morph catenae and the latter article, which is in English, provides a dependency grammar account of clitics based upon the catena.

- ^ Groß and Osborne (2013) demonstrate the applicability of the catena concept to the syntax and morphosyntax of German, and Imrényi (2013a, 2013b: 98–100, 2013c) shows its utility for the analysis of verb combinations and clause structure in Hungarian.

- ^ This definition is closely similar to the definition of the catena unit given by Osborne and Groß (2012a: 174)

- ^ This formal definition of the catena unit is given in Osborne and Groß (2016: 117, n. 16).

- ^ Definitions and discussions of the four units string, catena, component, and constituent like those given here can be found in a number of places (e.g. Osborne et al. 2012: 358-359; Osborne and Groß 2016: 117-118; Osborne and Groß 2018: 167).

- ^ The enumeration of distinct strings, catena, components, and constituents as done here is a frequent means of establishing an understanding of the catena unit (e.g. Osborne and Groß 2016: 117-118; Osborne and Groß 2018: 167).

- ^ For Kunze's definition of the Teilbaum, see Kunze (1975:12).

- ^ The dependency constituent plays a central role in Pickering and Barry's (1993) account of coordination.

- ^ O'Grady's (1998) seminal article is on the importance of the catena unit for the syntactic analysis of idioms.

- ^ The term catena was first used in Osborne et al. article from 2012.

- ^ See the following articles to get a sense of the utility of the catena unit for the study of natural language syntax: Osborne (2005), Osborne et al. (2011), Osborne (2012), Osborne and Groß (2012a, 2012b), Osborne et al. (2012), and Osborne (2014: 620–624), Osborne and Groß (2018).

- ^ The insight that proper idioms are stored as catenae (and not as constituents) is the primary insight that first established the value and validity of the catena concept for syntactic analysis (e.g. O'Grady 1998; Osborne 2005: 272-275; Osborne and Groß 2012: 177-180)

- ^ The value of the catena unit for the anlaysis of ellipsis phenomena is established in Osborne (2005: 275-285) and Osborne et al. (2012: 379-392).

- ^ For examples and discussion of the elided material of gapping as a catena, see Osborne (2005: 275-280) and Osborne et al. (2012: 382-386).

- ^ For discussion and examples of the elided material of stripping as a catena, see Osborne (2005: 283-284) and Osborne et al. (2012: 382-386).

- ^ For examples and discussion of the elided material of answer fragments as catenae, see Osborne (2005: 284-285), Osborne et al. (2012: 381-382), and Osborne and Groß (2018).

- ^ For a discussion and many illustrations of predicates as catenae, see Osborne (2005: 260-270)

References

- O'Grady, W. 1998. The syntax of idioms. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16. 279–312.

- Groß, T. 2014. Clitics in dependency morphology. In Linguistics Today Vol. 215: Dependency Linguistics, ed. by E. Hajičová et al., pp. 229–252. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Groß, T. and T. Osborne 2013. Katena und Konstruktion: Ein Vorschlag zu einer dependenziellen Konstruktionsgrammatik. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 32, 1, 41–73.

- Imrényi, A. 2013a. The syntax of Hungarian auxiliaries: a dependency grammar account. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Dependency Linguistics (DepLing 2013). Prague, August 27–30, 2013. Charles University in Prague / Matfyzpress. 118–127.

- Imrényi A. 2013b. A magyar mondat viszonyhálózati modellje. (A relational network model of the Hungarian clause.) Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. (154 pages).

- Imrényi, A. 2013c. Constituency or dependency? Notes on Sámuel Brassai's syntactic model of Hungarian. In: Szigetvári, Péter (ed.), VLlxx. Papers Presented to László Varga on his 70th Birthday. Budapest: Tinta. 167–182.

- Kunze, J. 1975. Abhängigkeitsgrammatik. Studia Grammatica XII. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

- Osborne, T. 2005. Beyond the constituent: A DG analysis of chains. Folia Linguistica 39, 3–4. 251–297.

- Osborne, T. 2012. Edge features, catenae, and dependency-based Minimalism. Linguistic Analysis 34, 3–4, 321–366.

- Osborne, T. 2014. Dependency grammar. In The Routledge Handbook of Syntax, ed. by A. Carnie, Y. Sato, and D. Saddiqi, pp. 604–626. London: Routledge.

- Osborne, T. 2015. Dependency grammar. In Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft/Handbooks of Linguistics and communication Science (HSK) 42, 2, 1027–1044.

- Osborne, T. 2019. Ellipsis in Dependency Grammar. In Jeroen van Craenenbrock and Tanja Temmerman (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Ellipsis, 142–161. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Osborne, T. 2019. A Dependency Grammar of English: An Introduction and Beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.224

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012a. Constructions are catenae: Construction Grammar meets Dependency Grammar. Cognitive Linguistics 23, 1, 163–214.

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß 2012b. Antecedent containment: A dependency grammar solution in terms of catenae. Studia Linguistica 66, 2, 94–127.

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß. 2016. The do-so-diagostic: Against finite VPs and for flat non-finite VPs. Folia Linguistica 50, 1, 97–35.

- Osborne, T. and T. Groß. 2018. Answer fragments. The Linguistic Review 35, 1, 161–186.

- Osborne, T., M. Putnam, and T. Groß. 2011. Bare phrase structure, label-less trees, and specifier-less syntax: Is Minimalism becoming a dependency grammar? The Linguistic Review 28: 315–364.

- Osborne, T., M. Putnam, and T. Groß 2012. Catenae: Introducing a novel unit of syntactic analysis. Syntax 15, 4, 354–396.

- Pickering, M. and G. Barry 1993. Dependency categorial grammar and coordination. Linguistics 31, 855–902.