Purgatorius

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2010) |

| Purgatorius Temporal range: Late Cretaceous-Paleocene,

| |

|---|---|

| |

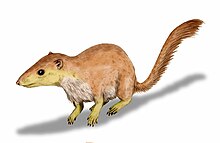

| Life restoration of P. unio | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Plesiadapiformes |

| Family: | †Purgatoriidae |

| Genus: | †Purgatorius Valen & Sloan, 1965 |

| Type species | |

| †Purgatorius unio Valen & Sloan, 1965

| |

| Species | |

Purgatorius is a genus of four extinct eutherian species typically believed to be the earliest example of a primate or a proto-primate, a primatomorph precursor to the Plesiadapiformes, dating to as old as 66 million years ago.[1] The first remains (P. unio and P. ceratops) were reported in 1965,[2] from what is now eastern Montana's Tullock Formation (early Paleocene, Puercan), specifically at Purgatory Hill (hence the animal's name) in deposits believed to be about 63 million years old, and at Harbicht Hill in the late Cretaceous and lower Paleocene Hell Creek Formation. Both locations are in McCone County.

They have also been found in the Ravenscrag Formation and widely discovered in the early Paleocene Bug Creek fauna, along with leptictids.[3] These deposits were once thought to be latest Cretaceous, but it is now clear that they are Paleocene channels with time-averaged fossil assemblages. It is thought to have been rat-sized 6 in (15 cm) long and 1.3 ounces (about 37g) and a diurnal insectivore, who burrowed through small holes in the ground.

Description of remains

Postcanine dentition of P. unio is documented by 13 dentulous, fragmentary mandibles, a fragmentary maxillary and more than 50 isolated teeth from Garbani Locality 80 km west of Purgatory Hill. P. ceratops is represented by an isolated lower molar found at Harbicht Hill, McCone County.[4] The report of the occurrence of Purgatorius in the Late Cretaceous was based on an isolated, worn molar found in a channel filling that contains early Puercan fossils. It is also abundantly represented in Pu 2-3 local faunas in the northern Western interior, suggesting that it came into the area between 64.75 and 64.11 Mya. Fragmentary dentition from the Garbani Channel fauna from Purgatorius janisae shows that the lower dental formula was 3.1.4.3.[5]

Dentition

The type specimen of P. unio, a damaged upper molar, is essentially identical to teeth found at the Garbani Locality. Data from this sample support Van Valen and Sloan's identification of topotypic lower molars, and also demonstrate that the lower dentition of P. unio includes seven postcanines. The alveolus for the single root of P1, crown unknown, is smaller than those for the canine or P2. The second lower pre- molar is smaller than P3; both are two- rooted. The fourth lower premolar is submolariform. A metaconid is lacking, although on some teeth slight thickenings of the enamel are present in this region. Talonid cusps are slightly differentiated. The first and second lower molars are approximately the same length (M1, average length x=- 1.93 mm, N- 13; M2, x=2.00 mm, N- 9); M. is longer (x= 2.32 mm, N -7). Widths of talonids of M1.2 vary from less than to greater than widths of trigonids. Hypoconulid of M. is enlarged, salient, and on some teeth incipiently doubled by addition of a lingual cusp.

Ankle bones

Bones from the ankle are similar to those of primates, and were suited for a life up in trees.[6]

Relationship

For many years, there has been debate as to whether Purgatorius is a primitive member of the primates or a basal member of the Plesiadapiforms. Several characters of the dentition of Purgatorius, which includes its incisor morphology, can ally it with later plesiadapiforms. The prism cross sections are highly variable with circular, horseshoe and irregular shapes, while the prisms of cheek teeth are radially arranged.[7] Due to the fragmentary dentaries found in the Garbani Channel fauna from Purgatorius janisae the morphology of the canine and incisor alveoli suggest the derived gradient in the crown size of: I1>or = I2>I3<C. Isolated upper incisors referable from P. janisae exhibit some typical plesiadapiform specializations. Due to general morphology of the postcanine dentition of Purgatorius, it could be expected to be characterized as a primitive member of the primates. However, due to the specializations of its incisors of P. janisae it is considered by some investigators as a basal member of the Pleasiadapiformes sensu lato.[5]

A phylogenetic analysis of 177 mammal taxa (mostly Cretaceous and Palaeocene fossils), published in 2015, suggests that Purgatorius may not be closely related to primates at all, but instead falls outside crown-group placentals - specifically as the sister taxon to Protungulatum. Similar results had been obtained in previous studies with far fewer species.[8]

Notes

- ^ O'Leary, M. A.; et al. (2013). "The placental mammal ancestor and the post–K-Pg radiation of placentals". Science. 339 (6120): 662–667. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..662O. doi:10.1126/science.1229237. PMID 23393258.

- ^ Van Valen, L.; Sloan, R. (1965). "The earliest primates". Science. 150 (3697): 743–745. Bibcode:1965Sci...150..743V. doi:10.1126/science.150.3697.743. PMID 5891702.

- ^ Lillegraven, Kielan-Jaworowska & Clemens 1979

- ^ Clemens, William (May 24, 1974). "Purgatorius, an Early Paromomyid Primate". Science. 184 (4139): 903–05. Bibcode:1974Sci...184..903C. doi:10.1126/science.184.4139.903. PMID 4825891.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Clemens 2004

- ^ Kaplan, M. (2012). "Primates were always tree-dwellers". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11423.

- ^ Clemens, W. A., and W. V. Koenigswald. "Purgatorius, plesiadapiforms, and evolution of Hunter–Schreger bands." J. Vertebr. Paleontol 11 (1991). Cited by Tabuce, Rodolphe; Delmer, Cyrille; Gheerbrant, Emmanuel (2007). "Evolution of the tooth enamel microstructure in the earliest proboscideans (Mammalia)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 149 (4): 611–28. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00272.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Halliday, Thomas J. D.; Upchurch, Paul; Goswami, Anjali (2017). "Resolving the relationships of Paleocene placental mammals" (PDF). Biological Reviews. 92 (1): 521–550. doi:10.1111/brv.12242. PMC 6849585. PMID 28075073.

References

- "Animal Armageddon: Purgatorius". Animal Planet Videos. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Bloch, Jonathon; Silcox, M. T.; Boyer, D. M.; Sargis, E. J. (2006). "New Paleocene skeletons and the relationship of plesiadapiforms to crown-clade primates". PNAS. 104 (4): 1159–1164. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.1159B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610579104. PMC 1783133. PMID 17229835.

- Buckley, G. (1997). "A New Species of Purgatorius (Mammalia; Primatomorpha) from the lower Paleocene Bear Formation, Crazy Mountains Basin, south-central Montana". Journal of Paleontology. 71 (1): 149–155. doi:10.1017/S0022336000039032. JSTOR 1306549.

- Clemens, William (May 24, 1974). "Purgatorius, an Early Paromomyid Primate". Science. 184 (4139): 903–05. Bibcode:1974Sci...184..903C. doi:10.1126/science.184.4139.903. PMID 4825891.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clemens, William (2004). "Purgatorius (Plesiadapiformes, Primates?, Mammalia), A Paleocene Immigrant into Northeastern Montana: Stratigraphic Occurrences and Incisor Proportions". Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. 36: 3–13. doi:10.2992/0145-9058(2004)36[3:PPPMAP]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - France, Diane L (2004). Lab Manual and Workbook for Physical Anthropology (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

- Lillegraven, Jason A.; Kielan-Jaworowska, Zofia; Clemens, William A. (1979). Mesozoic Mammals The First two-thirds of Mammalian History. University of California. ISBN 9780520035829.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Mikko's Phylogeny Archive". Archived from the original on 2006-05-04.

- Van Valen, L. (1994). "The origin of the plesiadapid primates and the nature of Purgatorius". Evolutionary Monographs. 15: 1–79.

- Van Valen, L.; Sloan, R. (1965). "The earliest primates". Science. 150 (3697): 743–745. Bibcode:1965Sci...150..743V. doi:10.1126/science.150.3697.743. PMID 5891702.