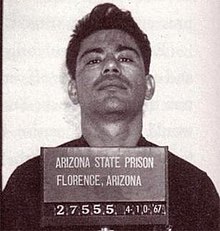

Ernesto Miranda

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

Ernesto Arturo Miranda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 9, 1941 Mesa, Arizona, U.S. |

| Died | January 31, 1976 (aged 34) Phoenix, Arizona, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Stabbing |

| Resting place | City of Mesa Cemetery |

| Occupation | Laborer |

| Criminal status | Convicted |

| Conviction(s) | Kidnapping and raping an 18-year-old woman |

Ernesto Arturo Miranda (March 9, 1941 – January 31, 1976) was a laborer whose conviction on kidnapping, rape, and armed robbery charges based on his confession under police interrogation was set aside in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Miranda v. Arizona, which ruled that criminal suspects must be informed of their right against self-incrimination and their right to consult with an attorney before being questioned by police. This warning is known as a Miranda warning.

After the Supreme Court decision set aside Miranda's initial conviction, the state of Arizona tried him again. At the second trial, with his confession excluded from evidence, he was convicted.

Biography

Early life

Ernesto Arturo Miranda was born in Mesa, Arizona, on March 9, 1941. Miranda began getting in trouble when he was in grade school. Shortly after his mother died, his father remarried. Miranda and his father didn't get along very well; he kept his distance from his brothers and stepmother as well. Miranda's first criminal conviction was during his eighth grade year. The following year, he was convicted of burglary and sentenced to a year in reform school.

In 1956, about a month after his release from the reform school, Arizona State Industrial School for Boys (ASISB), he fell afoul of the law once more and was returned to ASISB. Upon his second release from reform school he relocated to Los Angeles, California. Within months of his arrival in LA, Miranda was arrested (but not convicted) on suspicion of armed robbery and for some sex offenses. After two and a half years in custody the 18-year-old Miranda was extradited back to Arizona.

He drifted through the southern U.S. for a few months, spending time in jail in Texas for living on the street without money or a place to live, and was arrested in Nashville, Tennessee, for driving a stolen car. Miranda was sentenced to a year and a day in the federal prison system because he had taken the stolen vehicle across state lines. He spent his sentence in Chillicothe, Ohio, and later in Lompoc, California.

The next couple of years Miranda kept out of jail, working at various places, until he became a laborer on the night loading dock for the Phoenix produce company. At that time he started living with Twila Hoffman, a 29-year-old mother of a boy and a girl by another man, from whom she could not afford a divorce.

Confession without rights; Miranda v. Arizona

On March 13, 1963,[1] Miranda's truck was spotted and license plates recognized by the brother of an 18-year-old kidnapping and rape victim, Lois Ann Jameson (the victim had given the brother a description). With his description of the car and a partial license plate number, Phoenix police officers Carroll Cooley and Wilfred Young confronted Miranda, who voluntarily accompanied them to the station house and participated in a lineup. At the time, Miranda was a person of interest, and not formally in custody.

After the lineup, when Miranda asked how he did, the police implied that he was positively identified. The police got a confession out of Miranda after two hours of interrogation, without informing him of his rights. After unburdening himself to the officers, Miranda was taken to meet the beating victim for positive voice identification. Asked by officers, in her presence, whether this was the victim, he said, "That's the girl." The victim stated that the sound of Miranda's voice matched that of the culprit.

Miranda then wrote his confessions down. At the top of each sheet was the printed certification that "…this statement has been made voluntarily and of my own free will, with no threats, coercion or promises of immunity and with full knowledge of my legal rights, understanding any statement I make can and will be used against me." Despite the statement on top of the sheets that Miranda was confessing "with full knowledge of my legal rights," he was not informed of his right to have an attorney present or of his right to remain silent. 73-year-old Alvin Moore was assigned to represent him at his trial. The trial took place in mid-June 1963 before Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Yale McFate.

Moore objected to entering the confession by Miranda as evidence during the trial but was overruled. Mostly because of the confession, Miranda was convicted of rape and kidnapping and sentenced to 20 to 30 years on both charges. Moore appealed to the Arizona Supreme Court, but the conviction was upheld.

Filing as a pauper, Miranda submitted his plea for a writ of certiorari, or request for review of his case to the U.S. Supreme Court in June 1965. After Alvin Moore was unable to take the case because of health reasons, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) attorney Robert J. Corcoran, asked John J. Flynn, a criminal defense attorney, to serve pro bono, along with his partner, John P. Frank, and associates Paul G. Ulrich and Robert A. Jensen [2] of the law firm Lewis & Roca in Phoenix to represent Miranda.[3] They wrote a 2,500 word petition for certiorari that argued that Miranda's Fifth Amendment rights had been violated and sent it to the United States Supreme Court.

Miranda v. Arizona

In November 1965, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Miranda's case, Miranda v. Arizona, along with three other similar cases to clear all misunderstandings created by the ruling of Escobedo v. Illinois. That previous case had ruled that:

Under the circumstances of this case, where a police investigation is no longer a general inquiry into an unsolved crime but has begun to focus on a particular suspect in police custody who has been refused an opportunity to consult with his counsel and who has not been warned of his constitutional right to keep silent, the accused has been denied the assistance of counsel in violation of the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments, and no statement extracted by the police during the interrogation may be used against him at a trial. Crooker v. California, 357 U.S. 433, and Cicenia v. Lagay, 357 U.S. 504, distinguished, and, to the extent that they may be inconsistent with the instant case, they are not controlling. 479–492.[4]

In January 1966, Flynn and Frank submitted their argument stating that Miranda's Sixth Amendment right to counsel had been violated by the Phoenix Police Department. Two weeks later the state of Arizona responded by stating that Miranda's rights had not been violated. The first day of the case was on the last day of February 1966. Because of the three other cases and other information the case had a second day of oral arguments on March 1, 1966.

John Flynn for Miranda outlined the case and then stated that Miranda had not been advised of his right to remain silent when he had been arrested and questioned, adding the Fifth Amendment argument to his case. Flynn contended that an emotionally disturbed man like Miranda, who had a limited education, should not be expected to know his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself.

Gary Nelson spoke for the people of Arizona, arguing that this was not a Fifth Amendment issue but just an attempt to expand the Sixth Amendment Escobedo decision. He urged the justices to clarify their position, but not to push the limits of Escobedo too far. He then told the court that forcing police to advise suspects of their rights would seriously obstruct public safety.

The second day concerned arguments from related cases. Thurgood Marshall, the former NAACP attorney, was the last to argue. In his capacity as the Solicitor General, he presented the Johnson administration's view of the case: that the government did not have the resources to appoint a lawyer for every indigent person who was accused of a crime.

Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the opinion in Miranda v. Arizona. The decision was in favor of Miranda. It stated that:

The person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him.

The opinion was released on June 13, 1966. Because of the ruling, police departments around the country started to issue Miranda warning cards to their officers to recite. They read:

You have the right to remain silent. If you give up the right to remain silent, anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney and to have an attorney present during questioning. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided to you at no cost. During any questioning, you may decide at any time to exercise these rights, not answer any questions or make any statements. Do you understand these rights as I have read them to you?

Life after Miranda v. Arizona

The Supreme Court set aside Miranda's conviction, which was tainted by the use of the confession that had been obtained through improper interrogation. The state of Arizona retried him. At the second trial, his confession was not introduced into evidence, but he was convicted again, based on testimony given by his estranged common law wife. He was sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison.[5]

Miranda was paroled in 1972.[5] After his release, he started selling autographed Miranda warning cards for $1.50.[6] Over the next few years, Miranda was arrested numerous times for minor driving offenses and eventually lost his license. He was arrested for the possession of a gun but the charges were dropped. However, because this violated his parole, he was sent back to Arizona State Prison for another year.

On January 31, 1976, after his release for violating his parole, a violent fight broke out in a bar in downtown Phoenix named La Amapola. Miranda received a lethal wound from a knife, and he was pronounced dead on arrival at Good Samaritan Hospital. Several Miranda cards were found on his person. The prime suspects in his killing were read their Miranda rights, did not implicate themselves, and were never prosecuted.[6] Miranda was buried in the City of Mesa Cemetery in Mesa, Arizona.[7][8]

References

- ^ Roger J. R. Levesque, The Psychology and Law of Criminal Justice Processes (Nova Publishers, 2006) p212

- ^ Paul G. Ulrich, Miranda v Arizona: History, Memories, and Perspectives, 7 Phoenix Law Review 203 (Winter 2013)

- ^ "Explore the History of Lewis and Roca" – see section: "1966 – Miranda v. Arizona". Lewis & Roca. Archived from the original on 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ^ "Escobedo v. Illinois". Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ a b Lief, Michael S.; H. Mitchell Caldwell (Aug–Sep 2006). "You Have The Right To Remain Silent". American Heritage. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2011-08-24.

- ^ a b Kelly, Jack (2017-06-13). "The Miranda Decision – 51 Years Later". American Heritage. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ^ "Miranda Stabbing Suspect Caught". Kingman Daily Miner. Phoenix. Associated Press. 3 February 1976.

- ^ Ernesto Arturo Miranda at Find a Grave

External links

- Court TV

- Lewis & Roca Firm History, Miranda Vs. Arizona at the Wayback Machine (archived May 14, 2008)

- MIRANDA v. ARIZONA, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)

- Miranda case

- 1941 births

- 1976 deaths

- 1976 murders in the United States

- 20th-century American criminals

- American male criminals

- American murder victims

- American people convicted of kidnapping

- American people convicted of rape

- American prisoners and detainees

- Burials in Arizona

- Criminals from Arizona

- Deaths by stabbing in Arizona

- Miranda warning case law

- Murdered criminals

- People from Mesa, Arizona

- People murdered in Arizona

- Prisoners and detainees of Arizona

- American people of Mexican descent