Diamond (dog)

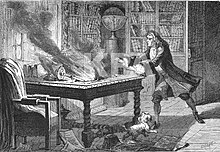

Diamond was, according to legend, Sir Isaac Newton's favourite dog, which, by upsetting a candle, set fire to manuscripts containing his notes on experiments conducted over the course of twenty years. According to one account, Newton is said to have exclaimed: "O Diamond, Diamond, thou little knowest the mischief thou hast done."[1] The story is largely apocryphal: according to another account, Newton simply left a window open when he went to church, and the candle was knocked over by a gust of wind.[2] In fact, some historians claim that Newton never owned pets.[1]

It is also possible that he had a cut piece of glass or gemstone that he referred to as "Diamond", from his famous work in optics. Such a diamond may have easily focused the light from the open window and started the fire that consumed his work. Apocryphal accounts of this event aside, consider if such an intelligent man would have left an open flame unattended for any amount of time.

The story of "Newton's Mischief" has been reproduced over the centuries as early as 1833 in "The Life of Sir Isaac Newton"[3] by David Brewster and later in St. Nicholas Magazine.[4] In 1816 Walter Scott used the story in the third of his Waverley Novels, The Antiquary (volume 2, chapter 1).

This pet of Newton's was also mentioned in Thomas Carlyle's book The French Revolution: A History, employed in discussing the deathbed of Louis XV. Carlyle writes "To the eye of History many things, in that sick room of Louis, are now visible, which to the courtiers there present were invisible. For indeed it as been well said, 'in every object there is inexhaustible meaning; the eye sees in it what the eye brings means of seeing.' To Newton and to Newton's dog Diamond, what a different pair of Universes; while the painting on the optical retina of both was, most likely, the same!"

Nevertheless, Diamond is the subject of several anecdotes concerning Newton. In another tale, Newton is said to have claimed that the dog discovered two theorems in a single morning. He added, however, that "one had a mistake and the other had a pathological exception."[5]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Alfred Rupert Hall, Isaac Newton: Eighteenth Century Perspectives, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 175. ISBN 0-19-850364-4.

- ^ Jason Socrates Bardi, The Calculus Wars: Newton, Leibniz, and the Greatest Mathematical Clash of All Times. Thunder's Mouth Press, 2006, p. 159. ISBN 1-56025-706-7.

- ^ The Life of Sir Isaac Newton

- ^ St. Nicholas Magazine, Vol. 5, No. 4, (February 1878)

- ^ "Historical Canines," Shepherd Software. Retrieved September 16, 2007.