Pelycosaur

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

| "Pelycosaurs" Temporal range: Pennsylvanian - Capitanian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of Dimetrodon mileri, Harvard Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Reptiliomorpha |

| Clade: | Amniota |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Informal group: | †Pelycosauria |

The pelycosaurs (pronounced PEL-ih-ko-saurz) were previously considered an order, but are now only an informal grouping composed of basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, sometimes called "mammal-like reptiles". They consist of all synapsids excluding the therapsids and their descendants.

Because more advanced synapsid group therapsida evolved directly from the pelycosaurs, the pelycosaurs are paraphyletic. Thus the name "pelycosaurs," similar to the term "mammal-like reptiles," had fallen out of favor among scientists by the 21st century, and is only used informally, if at all, in the modern scientific literature.[1]

Etymology

The term pelycosaur has been fairly well abandoned by paleontologists because it no longer matches the features that distinguish a clade.[citation needed] The modern word was created from Greek πέλυξ pelyx 'wooden bowl' or 'axe' and σαῦρος sauros 'lizard'. The intended etymology presents a problem, since pelycosaur as created basically means 'basin lizard', but there is a ambiguity between several original Greek words in that pélix is 'wooden bowl' and pelíkē 'basin', whereas pélyx is 'ax' like pélekys 'double-edged ax'.[citation needed]

Pelycosauria is a paraphyletic taxon because it excludes the therapsids. For that reason, the term is sometimes avoided by proponents of a strict cladistic approach. Eupelycosauria is used to designate the clade that includes most Pelycosaurs, along with the Therapsida and the Mammals. In contrast to "Pelycosaurs", this is a monophyletic group. Caseasauria refers to a pelycosaur side-branch, or clade, that did not leave any descendants.[citation needed]

Evolutionary history

The pelycosaurs appear to have been a group of synapsids that have direct ancestral links with the mammals, having differentiated teeth and a developing hard palate. The pelycosaurs appeared during the Late Carboniferous and reached their apex in the early part of the Permian, remaining the dominant land animals for some 40 million years. A few continued into the Capitanian. They were succeeded by the therapsids.

Description

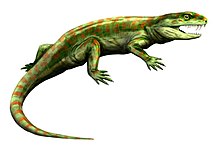

Some species were quite large, growing to a length of 3 metres (10 ft) or more, although most species were much smaller. Well-known pelycosaurs include the genera Dimetrodon, Sphenacodon, Edaphosaurus, and Ophiacodon.[2]

Pelycosaur fossils have been found mainly in Europe and North America, although some small, late-surviving forms are known from Russia and South Africa.

Unlike lepidosaurian reptiles, pelycosaurs lacked reptilian epidermal scales. Fossil evidence from some varanopids shows that parts of the skin were covered in rows of osteoderms, presumably overlain by horny scutes.[1] The belly was covered in rectangular scutes, looking like those present in crocodiles.[3] Parts of the skin not covered in scutes might have had naked, glandular skin like that found in some mammals. Dermal scutes are also found in a diverse number of extant mammals with conservative body types, such as in the tails of some rodents, sengis, moonrats, the opossums and other marsupials, and as regular dermal armour with underlying bone in the armadillo.

At least two pelycosaur clades independently evolved a tall sail, consisting of elongated vertebral spines: the edaphosaurids and the sphenacodontids. In life, this would have been covered by skin, and likely functioned as a thermoregulatory device[4] or as a mating display.

Taxonomy

In phylogenetic nomenclature, "Pelycosauria" is not used formally, since it does not constitute a group of all organisms descended from some common ancestor (a clade), because the group specifically excludes the therapsids which are descended from pelycosaurs. Instead, it represents a paraphyletic "grade" of basal synapsids leading up to the clade Therapsida.[citation needed]

In 1940, the group was reviewed in detail, and every species known at the time described, with many illustrated, in an important monograph by Alfred Sherwood Romer and Llewellyn Price.[5]

In traditional classification, the order Pelycosauria is paraphyletic in that the therapsids (the "higher" synapsids) have emerged from them. That means Pelycosauria is a grouping of animals that does not contain all descendants of its common ancestor, as is often required by phylogenetic nomenclature. In evolutionary taxonomy, Therapsida is a separated order from Pelycosauria, and mammals (having evolved from therapsids) are separated from both as their own class. This use has not been continued by a majority of scientists since the 1990s.[citation needed]

The following classification was presented by Benton in 2004.[6]

- Order Pelycosauria*

- Family Eothyrididae

- Family Caseidae

- Family Varanopidae

- Family Ophiacodontidae

- Family Edaphosauridae

- Family Sphenacodontidae

- Order Therapsida

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Botha-Brink, J.; Modesto, S.P. (2007). "A mixed-age classed 'pelycosaur' aggregation from South Africa: Earliest evidence of parental care in amniotes?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 274 (1627): 2829–2834. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0803. PMC 2288685. PMID 17848370.

- ^ Cowen, Richard (2013). History of Life. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-1-11851-093-3.

- ^ Carroll, R.L. (1969). "Problems of the origin of reptiles". Biological Reviews. 44 (3): 393–432. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1969.tb01218.x.

- ^ Tracy, C.R.; Turner, J.S.; Huey, R.B. (1986). "A biophysical analysis of possible thermoregulatoryadaptations in pelycosaurs". In MacLean, P.D.; Roth, J.J.; Roth, E.C.; Hotton, N. (eds.). Ecology and Biology of Mammal-Like Reptiles. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Press. pp. 195–205.

- ^ Romer, A.S.; Price, L.I. (1940). "Review of the Pelycosauria". Geol. Soc. Amer. Spec. Papers. Geological Society of America Special Papers. 28: 1–538. doi:10.1130/SPE28-p1.

- ^ Benton, Michael J. (2004). Vertebrate palaeontology (3rd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-632-05637-8.

References

- Reisz, R.R. (1986). Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie [Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology]. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. Part 17A Pelycosauria. ISBN 3-89937-032-5.

External links

- "Introduction to the Pelycosaurs". UCMP.

- "Synapsida - Pelycosauria". Palaeos. Archived from the original on 2006-03-13.