John Randolph Bray

John Randolph Bray | |

|---|---|

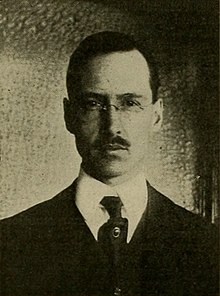

Bray in 1915 | |

| Born | August 25, 1879 |

| Died | October 10, 1978 (aged 99) Bridgeport, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Animator |

John Randolph Bray (August 25, 1879 – October 10, 1978) was an American animator.[1]

Work

Bray became interested in animation in the early years of moving pictures. By 1914, he opened a New York area studio specifically organized to make animated films.[2] Unlike newspaper cartoonist Winsor McCay, who had been making short animated films for several years, Bray organized his studio according to the principles of industrial production, an approach that Raoul Barré, another animator, also adopted at around the same time.[3]

As the 1910s progressed, Bray's studio became a powerhouse in the early animation industry. The studio assembled a staff that included many accomplished animators, and it produced a steady and widely distributed stream of animated shorts.[4] Bray contributed a series featuring his Colonel Heeza Liar series, which was among the most popular series of animated shorts in that era.[5]

Bray produced the first animated film in color, The Debut of Thomas Cat (1920), in Brewster Color.[6][7] Bray Productions produced over 500 films between 1913 and 1937, mostly animation films and documentary shorts. Cartoonist Paul Terry worked briefly for Bray Studios in 1916.

The entertainment branch of Bray Pictures Corporation closed in 1928. Documentary production for theatrical release continued through the late 1930s. The educational and commercial branch, Brayco, made mostly filmstrips from the 1920s until it closed in 1963. Bray Studios was still in operation in the early 1980s. J.R. Bray died in Bridgeport, CT at the age of 99 in 1978.

Jam Handy's company, the Jam Handy Organization, began as a Chicago-Detroit division of Bray Studios, to service the auto industry's need for industrial films. Jam Handy made several thousand industrial and sponsored films and tens of thousands of filmstrips, many for the auto industry, closed in 1983.

Bray visited Winsor McCay during his production of Gertie the Dinosaur and claimed to be a journalist writing an article about animation. McCay was very open about the techniques that he developed and showed all the details to Bray. John Randolph Bray later patented many of McCay's methods and unsuccessfully tried to sue the other animator; McCay prevailed, however, and received royalties from Bray for several years thereafter.[8]

References

- ^ Loc.gov

- ^ Clarke, James (2007). Animated Films. Virgin Books. pp. 13. ISBN 978-0753512586.

- ^ Wells, Paul (2002). Animation: Genre and Authorship. Wallflower Press. p. 115.

- ^ Arnold, G. B. (2016). Animation and the American Imagination: A Brief History. Praeger. pp. 23–27. ISBN 978-1440833595.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780198020790.

- ^ Kroon, Richard W. (2010). A/V A to Z: An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Media, Entertainment, and Other Audiovisual Terms. McFarland. p. 46. ISBN 9780786444052.

- ^ Robertson, Patrick (November 11, 2011). Robertson's Book of Firsts: Who Did What for the First Time. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 326. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ Crafton, Donald (1993). Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898-1928. University of Chicago Press. p. 376. ISBN 9780226116679.