Tomb of Kha and Merit

| TT8 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Kha and Merit | |

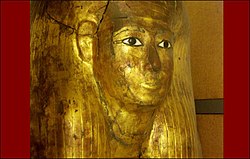

The gilded inner coffin of Kha from his TT8 tomb (now in the Museo Egizio of Turin) | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′N 32°36′E / 25.733°N 32.600°E |

| Location | Theban Tombs |

| Discovered | 1906 |

| Excavated by | Arthur Weigall and Ernesto Schiaparelli |

← Previous TT7 Next → TT9 | |

| ||||||||

| Kha and Meryt in hieroglyphs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | ||||||||

TT8 or Theban Tomb 8 was the tomb of Kha, the overseer of works from Deir el-Medina in the mid-18th dynasty[2] and his wife, Merit. TT8 was one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of ancient Egypt, one of few tombs of nobility to survive intact. It was discovered by Arthur Weigall and Ernesto Schiaparelli in 1906 on behalf of the Italian Archaeological Mission.[3] Its discoverers used 250 workers to dig in pursuit of the tomb for several weeks. The pyramid-chapel of Kha and Merit was already well-known for many years; scenes from the chapel had already been copied in the 19th century by several Egyptologists, including John Gardiner Wilkinson and Karl Lepsius.[4] Egyptologists also knew that Kha was an important foreman at Deir El-Medina, where he was responsible for projects constructed during the reigns of Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III.[5] The pyramidion of the chapel had been removed by an earlier visitor and was in the Louvre Museum.[6]

Schiaparelli was surprised to discover the tomb in the isolated cliffs surrounding the village and not in the immediate proximity of the chapel itself, as was conventionally the case for other burials of Egyptian nobility.[6]

Tomb objects

The items found in the tomb show that Kha and Merit were quite wealthy during their lifetime. Unlike the more chaotic burial of Tutankhamun, the burials of Kha and Merit were carefully planned out. Important items were covered by dust sheets and the floor was swept by the last person to leave the tomb.[7]

The coffins of Kha and Merit were buried in two nested coffins; Kha's mummy was tightly wrapped and several items of jewelry were included within the wrappings. The two anthropoid coffins of Kha are excellent examples of the wealth and technically brilliant workmanship of the arts during the reign of Amenhotep III. Kha's outer coffin "was covered with black bitumen, with the face, hands, alternate stripes of the wig, bands of inscriptions and figures of funerary gods [all] in gilded gesso."[8] Kha's inner coffin was:

"entirely covered in gold leaf, except for the eyes, eye-brows and cosmetic lines, which are inlaid--quartz or rock crystal for the whites of the eyes, black glass or obsidian for the irises, blue glass for the eyebrows and cosmetic lines. The eye sockets themselves are framed with copper or bronze. His arms are crossed over his chest in the pose of Osiris, lord of the dead. He wears a broad collar with falcon-head terminals. Below this is a vulture with outstretched wings grasping two shen-signs in its talons."[9]

Included in one of Kha's coffins is one of the earliest examples of the Egyptian Book of the Dead.[7] An x-ray of Kha's mummy shows that it was "adorned with a gold necklace and heavy earrings, one of the earliest examples yet found of men wearing earrings."[6]

Merit was buried in a single outer coffin with one inner anthropoid coffin and a cartonnage mask. Her mummy was loosely wrapped with funerary jewellery. A tomb of this magnitude would have taken years to prepare, a process that Kha certainly oversaw during his lifetime. Unexpectedly predeceased by Merit, Kha donated his own coffin to his wife. Since it was too big for Merit’s mummy, Kha was forced to pack linens, monogrammed for him, around her mummy. Merit's single coffin combines features of Kha's inner and outer coffins; "the lid is entirely gilded, but the box is covered with black bitumen, with only the figures and inscriptions gilded."[9]

Both Kha's and Merit's anthropoid coffins were contained within Middle Kingdom style "rectangular outer coffins covered with black bitumen and having vaulted, gable-ended lids."[9] Kha's coffin was mounted on sledge runners, notes Ernesto Schiaparelli in his 1927 publication report of the discovery.[10]

The tomb was furnished with all the objects necessary in the afterlife. Ointments and kohl were regarded as a necessary part of hygiene and these precious materials were held in a variety of lidded alabaster, glass and faience vessels. Egyptians protected themselves from flies and from sunlight by wearing dark kohl under the eyes, depicted as a long cosmetic stripe on sculptures. Other objects in the tomb include sandals, jar vessels and more than 100 garments.[11]

Location of Kha's objects

All the funerary objects from Kha's tomb, except for two small articles, were subsequently transferred to the Egyptian museum in Turin.[6] Tomb TT8 was found at almost the same time as KV55 and less than two years after KV46, the tomb of Yuya and Tjuyu, which contained almost the same contents as TT8 and dated to only slightly later in the reign of Amenhotep III.

See also

- List of Theban tombs

- N. de Garis Davies, Nina and Norman de Garis Davies, Egyptologists

- Raffaella Bianucci, Michael E. Habicht, Stephen Buckley, Joann Fletcher, Roger Seiler, Lena M. Öhrström, Eleni Vassilika, Thomas Böni, Frank J. Rühli. Shedding New Light on the 18th Dynasty Mummies of the Royal Architect Kha and His Spouse Merit. PLOS One 2015 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131916

References

- ^ Porter and Moss, Topographical Bibliography: The Theban Necropolis, pg 16-17

- ^ David O'Connor & Eric Cline, Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign, University of Michigan Press, 1998. p.118

- ^ "index". xy2.org. Archived from the original on 2009-01-06. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- ^ "Deir El Medina: The Painted Tombs" in Christine Hobson, Exploring the World of the Pharaohs: A complete guide to Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, 1993 paperback, p.118

- ^ Hobson, p.118

- ^ a b c d Hobson, p.119

- ^ a b "The Archiect Kha, TT8". ib205.tripod.com. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- ^ Ernesto Schiaparelli, La tomba intatta dell'architeto Cha. In: Relazione sui lavori della missione archeologica Italiano in Egitto (Anno 1902-1920), 2. Turin, 1927. figures 21 & 23

- ^ a b c O'Connor & Cline, p.119

- ^ Schiaparelli, pp.17-20 & 28, figures 18 & 27

- ^ John H. Taylor, Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt, University of Chicago Press, 2001. p.108

External links

- Bibliography on TT8 Theban Mapping Project

- Scans of Norman and Nina De Garis Davies' tracings of Theban Tomb 8 (external).