Schweizer's reagent

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Cuoxam, Schweitzer's reagent

| |

| Identifiers | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.037.720 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| Properties | |

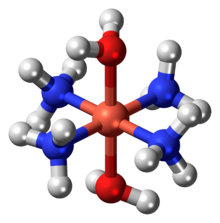

| [Cu(NH3)4(H2O)2](OH)2 | |

| Appearance | blue solid |

| Melting point | decomposes |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Schweizer's reagent is the metal ammine complex with the formula [Cu(NH3)4(H2O)2](OH)2. This deep-blue compound is used in purifying cellulose.

It is prepared by precipitating copper(II) hydroxide from an aqueous solution of copper sulfate using sodium hydroxide or ammonia, then dissolving the precipitate in a solution of ammonia.

It forms an azure solution. Evaporation of these solutions leaves light blue residue of copper hydroxide, reflecting the lability of the copper-ammonia bonding. If conducted under stream of ammonia, then deep blue needle-like crystals of the tetrammine form. In presence of oxygen, concentrated solutions give rise to nitrites Cu(NO2)2(NH3)n. The nitrate results from oxidation of the ammonia.[1][2]

Reactions with cellulose

Schweizer's reagent was once used in production of cellulose products such as rayon and cellophane. Cellulose, which is quite insoluble in water (hence its utility as clothing), dissolves in the presence of Schweizer's reagent. Using the reagent, cellulose can be extracted from wood pulp, cotton fiber, and other natural cellulose sources. Cellulose precipitates when the solution is acidified. It functions by binding to vicinal diols.[3]

Presently, the reagent is used in the analysis of the molecular weight of cellulose samples.[4]

History

These properties of Schweizer's reagent were discovered by the Swiss chemist Matthias Eduard Schweizer (1818–1860),[5] after whom the reagent is named.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Cudennec, Y.; et al. (1995). "Étude cinétique de l'oxydation de l'ammoniac en présence d'ions cuivriques" [Kinetic study of the oxidation of ammonia in the presence of cupric ions]. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série IIB. 320 (6): 309–316.

- ^ Cudennec, Y.; et al. (1993). "Synthesis and study of Cu(NO2)2(NH3)4 and Cu(NO2)2(NH3)2". Eur. J. Solid State Inorg. Chem. 30 (1–2): 77–85.

- ^ Burchard, Walther; Habermann, Norbert; Klüfers, Peter; Seger, Bernd; Wilhelm, Ulf (1994). "Cellulose in Schweizer's Reagent: A Stable, Polymeric Metal Complex with High Chain Stiffness". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 33 (8): 884–887. doi:10.1002/anie.199408841.

- ^ Krässig, Hans; Schurz, Josef; Steadman, Robert G.; Schliefer, Karl; Albrecht, Wilhelm; Mohring, Marc; Schlosser, Harald (2004). "Cellulose". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a05_375.pub2. ISBN 9783527303854.

- ^ (Schweizer, 1857), p. 110: "Dieselbe besitzt nämlich in ausgezeichnetem Grade das Vermögen, bei gewöhnlicher Temperatur Pflanzenfaser aufzulösen.

Uebergiesst man gereinigte Baumwolle mit der blauen Flüssigkeit, so nimmt erstere bald eine gallertartige schlüpfrige Beschaffenheit an, die Fasern gehen auseinander und verschwinden und nach einigem Durcharbeiten mit einem Glasstabe hat sich das Ganze in eine schleimige Flüssigkeit verwandelt. Dabei findet nicht die geringste Wärmeentwicklung statt. Hat man nicht eine hinreichende Menge der Flüssigkeit angewendet, so bleibt ein Theil der Fasern noch sichtbar; setzt man dann aber einen Ueberschuss der Lösung hinzu und schüttelt um, so erhält man eine beinahe klare blaue Lösung, die sich, nachdem sie mit Wasser verdünnt worden ist, filtriren lässt."

(It possesses, namely, to an outstanding degree the capacity to dissolve plant fibers at ordinary temperatures.

If one pours the blue liquid over cleaned cotton, then the former soon assumes a gelatinous, slippery texture, the fibers separate and vanish, and after some kneading with a glass rod, the whole transformed into a slimy liquid. During this, not the least evolution of heat occurred. If one did not use a sufficient quantity of liquid, then a portion of the fibers still remained visible; however, if one then adds an excess of the solution and shakes it, then one obtains a nearly clear blue solution, which, after it has been diluted with water, can be filtered.)

References

- Walther Burchard; Norbert Habermann; Peter Klüfers; Bernd Seger; Ulf Wilhelm (1994). "Cellulose in Schweizer's Reagent: A Stable, Polymeric Metal Complex with High Chain Stiffness". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 33 (8): 884–887. doi:10.1002/anie.199408841.

- Eduard Schweizer (1857). "Das Kupferoxyd-Ammoniak, ein Auflösungsmittel für die Pflanzenfaser" [Copper ammonium oxide, a solvent for plant fibers]. Journal für praktische Chemie. 72 (1): 109–111. doi:10.1002/prac.18570720115.

- George B Kauffman (1984). "Eduard Schweizer (1818-1860): The Unknown Chemist and His Well-Known Reagent". J. Chem. Educ. 61 (12): 1095–1097. Bibcode:1984JChEd..61.1095K. doi:10.1021/ed061p1095.