Fixed price of Coca-Cola from 1886 to 1959

Between 1886 and 1959, the price of a 6.5-oz glass or bottle of Coca-Cola was set at five cents, or one nickel, and remained fixed with very little local fluctuation. The Coca-Cola Company was able to maintain this price for several reasons, including bottling contracts the company signed in 1899, advertising, vending machine technology, and a relatively low rate of inflation.[1] The fact that the price of the drink was able to remain the same for over seventy years is especially significant considering the events that occurred during that period, including the founding of Pepsi, World War I, Prohibition, changing taxes, a caffeine and caramel shortage, World War II, and the company's desire to raise its prices. Much of the research on this subject comes from "The Real Thing": Nominal Price Rigidity of the Nickel Coke, 1886–1959, a 2004 paper by economists Daniel Levy and Andrew Young.[2]

The beginning

In 1886, Dr. John Stith Pemberton, a pharmacist and former confederate soldier, produced the first Coca-Cola syrup. On May 8, 1886, he brought a jug of his syrup to a local pharmacy on Peachtree road in Atlanta, Georgia. According to the chronicle of Coca-Cola, "It was pronounced 'excellent' and placed on sale for five cents a glass".[3] Although most soda fountain drinks cost seven or eight cents at the time (for a 6.5 oz glass), Coca-Cola chose five cents and specifically marketed itself as an affordable option.[1] Pemberton sold his remaining stake in Coca-Cola to Asa Candler in 1888.

Bottling contracts

In 1899, Benjamin Thomas and Joseph Whitehead, two lawyers from Chattanooga, Tennessee, approached Coca-Cola President Asa Candler about buying Coca-Cola bottling rights. At the time, soda fountains were the predominant way of consuming carbonated beverages in the United States.[2] Candler sold the rights to the two lawyers for one dollar, which he never ended up collecting. It is speculated that Candler sold the bottling rights so cheaply because he (a) truthfully thought bottling would never take off, and (b) was granted the ability in the contract to "pull their franchise if they ever sold an inferior product".[4] Unfortunately for Candler, the contract at the agreed-upon price had no expiration date, so he had essentially agreed to sell Coca-Cola at the same price forever.

Advertising

Although Candler predicted differently, bottling did indeed become popular (surpassing fountain sales in 1928), and the non-expiring contract meant that Coca-Cola had to sell their syrup for a fixed price. That meant Coca-Cola's profits could be maximized only by maximizing the amount of product sold and that meant minimizing the price to the consumer. Toward this end, Coca-Cola began an aggressive marketing campaign to associate their product with the five-cent price tag, providing incentive for retailers to sell at that price even though a higher price at a lower volume might have made them more profit otherwise.[1] The campaign proved successful, and bottlers did not increase prices. Coca-Cola was able to renegotiate the bottling contract in 1921. However, in part because of the costs of rebranding (changing all of their advertisements as well as the psychological associations among consumers) the price of Coca-Cola remained at five cents until the late 1950s.[1]

Vending machines

Another reason the price of Coca-Cola remained fixed at five cents, even after 1921, was the prevalence of vending machines. In 1950, Coca-Cola owned over 85% of the 460,000 vending machines in the United States. Based on vending machine prices at the time, Levy and Young estimate the value (in 1992 dollars) of these vending machines at between $286 million and $900 million.[2]

Because existing Coca-Cola vending machines could not reliably make change, customers needed to have exact change. The Coca-Cola company feared that requiring multiple coins (e.g., six pennies or one nickel and one penny for six-cent Coke) would reduce sales and cost money to implement, among other things.[2] Reluctant to double the price to a dime — the next price achievable with a single coin — they were forced to keep the price of Coca-Cola at five cents, or seek more creative methods. This constraint played a role into the 1950s, when vending machines began to reliably make change.[2]

Attempts to raise prices

The Coca-Cola Company sought ways to increase the five cent price, even approaching the U.S. Treasury Department in 1953 to ask that they mint a 7.5 cent coin.[1] The Treasury was unsympathetic. In another attempt, The Coca-Cola Company briefly implemented a strategy where one in every nine vending machine bottles was empty.[1] The empty bottle was called an "official blank".[2] This meant that, while most nickels inserted in a vending machine would yield cold drinks, one in nine patrons would have to insert two nickels in order to get a bottle. This effectively raised the price to 5.625 cents.[1] Coca-Cola never implemented this strategy on a national scale.

The end of the fixed price of Coca-Cola

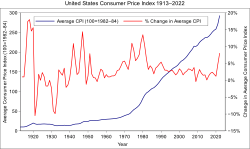

Throughout its history, the price of Coca-Cola had been especially sticky, but in the 1940s, inflation in the United States had begun to accelerate, making nickel Coke unsustainable. As early as 1950, Time reported Coca-Cola prices went up to six cents. In 1951, Coca-Cola stopped placing "five cents" on new advertising material, and Forbes Magazine reported on the "groggy" price of Coca-Cola.[2] After Coca-Cola president Robert Woodruff's plan to mint a 7.5 cent coin failed, Business Weekly reported Coke prices as high as 6, 7, and 10 cents, around the country. By 1959, the last of the nickel Cokes had been sold.[2]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g NPR. "Episode 416: Why The Price Of Coke Didn't Change For 70 Years". Planet Money. NPR, 13 Nov. 2012. Web.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Levy, Daniel; Young, Andrew (August 2004). ""The Real Thing": Nominal Price Rigidity of the Nickel Coke, 1886–1959" (PDF). Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 36 (4): 765–799. doi:10.1353/mcb.2004.0065. JSTOR 3839041.

- ^ "The Chronicle of Coca-Cola". The Chronicle of Coca-Cola. N.p., n.d. Web.

- ^ Laprad, David (23 July 2010). "A Brief History of the Chattanooga Coca-Cola Company". Hamilton County Herald.

- Karnasiewicz, Sarah. "Fizzy Business". Imbibe Magazine. N.p., July 2011. Web.

- Frandzel, Steve. "Economist: How Coke Stayed at a Nickel for Seven Decades". Emory University Home Page. N.p., 15 Nov. 2012. Web.

- Harford, Tim. "The Mystery of the 5-cent Coca-Cola". Slate Magazine. Slate, 2007. Web.

- "The Coca-Cola System". The Coca-Cola Company. N.p., n.d. Web.

- PLANET MONEY. Episode 416: "Why The Price of Coke Didn't Change For 70 years", https//www.npr.org/2019/05/01/719213730/episode-416-why-the-price-of-coke-didnt-change-for-70-years