Phlyax play

A Phlyax play (Ancient Greek: φλύαξ, also phlyakes), also known as a hilarotragedy, was a burlesque dramatic form that developed in the Greek colonies of Magna Graecia in the 4th century BCE. Its name derives from the Phlyakes or “Gossip Players” in Doric Greek. From the surviving titles of the plays they appear to have been a form of mythological burlesque, which mixed figures from the Greek pantheon with the stock characters and situations of Attic New Comedy.

Only five authors of the genre are known by name: Rhinthon and Sciras of Taranto, Blaesus of Capri, Sopater of Paphos and Heraklides. The plays themselves survive only as titles and a few fragments.[1] A substantial body of South Italian vases are thought to represent scenes of the phlyakes, giving rise to much speculation on Greek stagecraft and dramatic form.

Characteristics of the genre

Nossis of Locri provides the closest contemporary explanation of the genre in her epitaph for Rhinthon:

Pass by with a loud laugh and a kindly word

For me: Rhinthon of Syracuse am I,

The Muses’ little nightingale; and yet

For tragic farce I plucked an ivy wreath.[2]

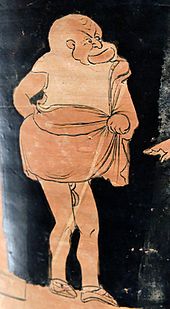

Textual and archaeological evidence give a partial picture of these burlesques of mythology and daily life. The absence of any surviving script has led to conjecture that they were largely improvised. The vase paintings indicate that they were performed on a raised wooden stage with an upper gallery, and that the actors wore grotesque costumes and masks similar to those of Attic Old Comedy. Acrobatics and farcical scenes were major features of the phlyax.

The phlyakes seems to die out by the late 3rd century, but the Oscan inhabitants of Campania subsequently developed a tradition of farces, parodies, and satires influenced by late Greek models, which became popular in Rome during the 3rd century BCE. This genre was known as Atellan farce, Atella being the name of a Campanian town. Atellan farce introduced a set of stock characters such as Maccus and Bucco to Latin comedy; even in antiquity, these were thought to be the ancestors of the characters found in Plautus,[3] and perhaps distantly of those of commedia dell'arte. Although an older view held that Attic comedy was the only source of Roman comedy, it has been argued that Rhinthon in particular influenced Plautus’s Amphitruo.[4]

The vase paintings

The so-called Phlyax vases are a principal source of information on the genre. By 1967, 185 of these vases had been identified.[5] Since depictions of theatre and especially comedy are rare in fabrics other than the South Italian, these have been thought to portray the distinctly local theatre tradition.[6] The vases first appeared at the end of the 5th century BCE, but most are 4th century. They represent grotesque characters, the masks of comedy, and the props of comic performance such as ladders, baskets, and open windows. About a quarter of them depict a low wooden temporary stage, but whether this was used in reality is a point of contention.[7]

Some scholars view the vases as depicting Attic Old Comedy rather than Phlyakes.[8] The Wurzburg Telephus Travestitus vase (bell krater, H5697) was identified in 1980 as a phlyax vase,[9] but Csapo[10] and Taplin[11] independently have argued that it actually represents the Thesmophoriazousai of Aristophanes.

References

- ^ See Rudolf Kassel, Colin Austin Poetae Comici Graeci, vol. I, pp. 257–88. 2001.

- ^ Anthologia Palatina 7.414

- ^ For instance, Horace, Epistles II, 1, 170 ff.

- ^ Z Stewart , The ‘Amphitrue’ of Plautus and Euripides ‘Bacchae’ TAPhA 89, 1958, 348–73.

- ^ Trendall, Phlyax Vases, 1967.

- ^ This argument was first made by H Heydemann in Die Phlyakendarstellungen der bemalten Vasen of 1886. Scholarship of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, in particular the work of Oliver Taplin, has cast doubt on this ascription of the vases to the phlyakes seeing them instead as depictions of Attic Old Comedy.

- ^ Margarete Bieber, The History of Greek and Roman Theater, 1961, takes a rather literal reading of this whereas W. Beare, The Roman Stage, 1964, insists this is a matter of the painter’s interpretation.

- ^ Trendall and Webster, Illustrations of Greek Drama, 1971, correlated Greek and Roman painted linen comic masks with their representation on the vases.

- ^ Kossatz-Deissmann, in Tainia: Festschrift für Roland Hampe, 1980

- ^ E. Csapo, A Note on the Wurzburg Bell-Krater H5697, Phoenix 40, 1986, 379–92.

- ^ O. Taplin, Classical Philology, Icongraphic Parody and Potted Aristophanes, Dioniso 57, 1987, 95–109, taking the vase as evidence that Attic Old Comedy was performed outside Athens after death of Aristophanes.

Bibliography

- Rudolf Kassel and Colin Austin. Poetae Comici Graeci, 2001.

- Klaus Neiiendam. Art of Acting Antiquity: Iconographical Studies in Classical, Hellenistic and Byzantine Theatre.

- Oliver Taplin. Comic Angels: And Other Approaches to Greek Drama Through Vase-Paintings.

- Arthur Dale Trendall. Phlyax Vases, 1967.

- AD Trendall and TBL Webster. Monuments Illustrating Greek Drama, 1971.