Boltzmann brain

The Boltzmann brain argument suggests that it is more likely for a single brain to spontaneously and briefly form in a void (complete with a false memory of having existed in our universe) than it is for our universe to have come about in the way modern science thinks it actually did. It was first proposed as a reductio ad absurdum response to Ludwig Boltzmann's early explanation for the low-entropy state of our universe.[1]

In this physics thought experiment, a Boltzmann brain is a fully formed brain, complete with memories of a full human life in our universe, that arises due to extremely rare random fluctuations out of a state of thermodynamic equilibrium. Theoretically, over an extremely large but not infinite amount of time, by sheer chance atoms in a void could spontaneously come together in such a way as to assemble a functioning human brain. Like any brain in such circumstances, it would almost immediately stop functioning and begin to deteriorate.[2]

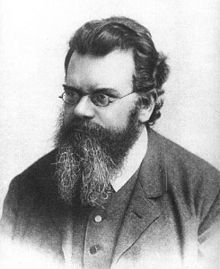

The idea is ironically named after the Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906), who in 1896 published a theory that tried to account for the fact that we find ourselves in a universe that is not as chaotic as the budding field of thermodynamics seemed to predict. He offered several explanations, one of them being that the universe, even one that is fully random (or at thermal equilibrium), would spontaneously fluctuate to a more ordered (or low-entropy) state. One criticism of this "Boltzmann universe" hypothesis is that the most common thermal fluctuations are as close to equilibrium overall as possible; thus, by any reasonable criterion, actual humans in the actual universe would be vastly less likely than "Boltzmann brains" existing alone in an empty universe.

Boltzmann brains gained new relevance around 2002, when some cosmologists started to become concerned that, in many existing theories about the Universe, human brains in the current Universe appear to be vastly outnumbered by Boltzmann brains in the future Universe who, by chance, have exactly the same perceptions that we do; this leads to the conclusion that statistically we ourselves are likely to be Boltzmann brains. Such a reductio ad absurdum argument is sometimes used to argue against certain theories of the Universe. When applied to more recent theories about the multiverse, Boltzmann brain arguments are part of the unsolved measure problem of cosmology. Boltzmann brains remain a thought experiment; physicists do not believe that we are actually Boltzmann brains, but rather use the thought experiment as a tool for evaluating competing scientific theories.

Boltzmann universe

In 1896, the mathematician Ernst Zermelo advanced a theory that the second law of thermodynamics was absolute rather than statistical.[3] Zermelo bolstered his theory by pointing out that the Poincaré recurrence theorem shows statistical entropy in a closed system must eventually be a periodic function; therefore, the Second Law, which is always observed to increase entropy, is unlikely to be statistical. To counter Zermelo's argument, the Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann advanced two theories. The first theory, now believed to be the correct one, is that the Universe started for some unknown reason in a low-entropy state. The second and alternative theory, published in 1896 but attributed in 1895 to Boltzmann's assistant Ignaz Schütz, is the "Boltzmann universe" scenario. In this scenario, the Universe spends the vast majority of eternity in a featureless state of heat death; however, over enough eons, eventually a very rare thermal fluctuation will occur where atoms bounce off each other in exactly such a way as to form a substructure equivalent to our entire observable universe. Boltzmann argues that, while most of the Universe is featureless, we do not see those regions because they are devoid of intelligent life; to Boltzmann, it is unremarkable that we view solely the interior of our Boltzmann universe, as that is the only place where intelligent life lives. (This may be the first use in modern science of the anthropic principle).[4][5]

In 1931, astronomer Arthur Eddington pointed out that, because a large fluctuation is exponentially less probable than a small fluctuation, observers in Boltzmann universes will be vastly outnumbered by observers in smaller fluctuations. Physicist Richard Feynman published a similar counterargument within his widely-read 1964 Feynman Lectures on Physics. By 2004, physicists had pushed Eddington's observation to its logical conclusion: the most numerous observers in an eternity of thermal fluctuations would be minimal "Boltzmann brains" popping up in an otherwise featureless universe.[4][6]

Spontaneous formation

In the universe's eventual state of ergodic "heat death", given enough time, every possible structure (including every possible brain) gets formed via random fluctuation. The timescale for this is related to the Poincaré recurrence time.[4][7][8] Boltzmann-style thought experiments focus on structures like human brains that are presumably self-aware observers. Given any arbitrary criteria for what constitutes a Boltzmann brain (or planet, or universe), smaller structures that minimally and barely meet the criteria are vastly and exponentially more common than larger structures; a rough analogy is how the odds of a real English word showing up when you shake a box of Scrabble letters are greater than the odds that a whole English sentence or paragraph will form.[9] The average timescale required for formation of a Boltzmann brain is vastly greater than the current age of the Universe. In modern physics, Boltzmann brains can be formed either by quantum fluctuation, or by a thermal fluctuation generally involving nucleation.[4]

Via quantum fluctuation

By one calculation, a Boltzmann brain would appear as a quantum fluctuation in the vacuum after a time interval of years. This fluctuation can occur even in a true Minkowski vacuum (a flat spacetime vacuum lacking vacuum energy). Quantum mechanics heavily favors smaller fluctuations that "borrow" the least amount of energy from the vacuum. Typically, a quantum Boltzmann brain would suddenly appear from the vacuum (alongside an equivalent amount of virtual antimatter), remain only long enough to have a single coherent thought or observation, and then disappear into the vacuum as suddenly as it appeared. Such a brain is completely self-contained, and can never radiate energy out to infinity.[10]

Via nucleation

Current evidence suggests that the vacuum permeating the observable Universe is not a Minkowski space, but rather a de Sitter space with a positive cosmological constant.[11]: 30 In a de Sitter vacuum (but not in a Minkowski vacuum), a Boltzmann brain can form via nucleation of non-virtual particles gradually assembled by chance from the Hawking radiation emitted from the de Sitter space's bounded cosmological horizon. One estimate for the average time required until nucleation is around years.[10] A typical nucleated Boltzmann brain will, after it finishes its activity, cool off to absolute zero and eventually completely decay, as any isolated object would in the vacuum of space. Unlike the quantum fluctuation case, the Boltzmann brain will radiate energy out to infinity. In nucleation, the most common fluctuations are as close to thermal equilibrium overall as possible given whatever arbitrary criteria are provided for labeling a fluctuation a "Boltzmann brain".[4]

Theoretically a Boltzmann brain can also form, albeit again with a tiny probability, at any time during the matter-dominated early universe.[12]

Modern Boltzmann brain problems

Many cosmologists believe that if a theory predicts that Boltzmann brains with human-like experiences vastly outnumber normal human brains, then that theory should be rejected.[4] Sean Carroll states "We're not arguing that Boltzmann Brains exist — we're trying to avoid them."[7] Scientists have used various expressions to explain why they are rejecting the hypothesis implying that we are Boltzmann brains. Caroll has stated that the hypothesis of you being a Boltzmann brain must be rejected due to "cognitive instability", the observation that your reasoning processes would be untrustworthy if you were indeed a Boltzmann brain.[13] Seth Lloyd has stated "they fail the Monty Python test: Stop that! That's too silly!" A New Scientist journalist summarizes that "the starting point for our understanding of the universe and its behaviour is that humans, not disembodied brains, are typical observers."[14] Brian Greene states: "I am confident that I am not a Boltzmann brain. However, we want our theories to similarly concur that we are not Boltzmann brains, but so far it has proved surprisingly difficult for them to do so."[15]

Some argue that brains produced via quantum fluctuation, and maybe even brains produced via nucleation in the de Sitter vacuum, don't count as observers. Quantum fluctuations are easier to exclude than nucleated brains, as quantum fluctuations can more easily be targeted by straightforward criteria (such as their lack of interaction with the environment at infinity).[4][10]

Some cosmologists believe that a better understanding of the degrees of freedom in the quantum vacuum of holographic string theory can solve the Boltzmann brain problem.[16]

In single-Universe scenarios

In a single de Sitter Universe with a cosmological constant, and starting from any finite spatial slice, the number of "normal" observers is finite and bounded by the heat death of the Universe. If the Universe lasts forever, the number of nucleated Boltzmann brains is, in most models, infinite; cosmologists such as Alan Guth worry that this would make it seem "infinitely unlikely for us to be normal brains".[9] One caveat is that if the Universe is a false vacuum that locally decays into a Minkowski or a Big Crunch-bound anti-de Sitter space in less than 20 billion years, then infinite Boltzmann nucleation is avoided. (If the average local false vacuum decay rate is over 20 billion years, Boltzmann brain nucleation is still infinite, as the Universe increases in size faster than local vacuum collapses destroy the portions of the Universe within the collapses' future light cones). Proposed hypothetical mechanisms to destroy the universe within that timeframe range from superheavy gravitinos to a heavier-than-observed top quark triggering "death by Higgs".[17][18][8]

If no cosmological constant exists, and if the presently observed vacuum energy is from quintessence that will eventually completely dissipate, then infinite Boltzmann nucleation is also avoided.[19]

In eternal inflation

One class of solutions to the Boltzmann brain problem makes use of differing approaches to the measure problem in cosmology: in infinite multiverse theories, the ratio of normal observers to Boltzmann brains depends on how infinite limits are taken. Measures might be chosen to avoid appreciable fractions of Boltzmann brains.[20][21][22] Unlike the single-universe case, one challenge in finding a global solution in eternal inflation is that all possible string landscapes must be summed over; in some measures, having even a small fraction of universes infested with Boltzmann brains causes the measure of the multiverse as a whole to be dominated by Boltzmann brains.[8][23]

The measurement problem in cosmology also grapples with the ratio of normal observers to abnormally early observers. In measures such as the proper time measure that suffer from an extreme "youngness" problem, the typical observer is a "Boltzmann baby" formed by rare fluctuation in an extremely hot, early universe.[12]

Identifying whether oneself is a Boltzmann observer

In Boltzmann brain scenarios, the ratio of Boltzmann brains to "normal observers" is astronomically large. Almost any relevant subset of Boltzmann brains, such as "brains embedded within functioning bodies", "observers who believe they are perceiving 3° microwave background radiation through telescopes", "observers who have a memory of coherent experiences", or "observers who have the same series of experiences as me", also vastly outnumber "normal observers". Therefore, under most models of consciousness, it is unclear that one can reliably conclude that oneself is not such a "Boltzmann observer", in a case where Boltzmann brains dominate the Universe.[4] Even under "content externalism" models of consciousness, Boltzmann observers living in a consistent Earth-sized fluctuation over the course of the past several years outnumber the "normal observers" spawned before a Universe's "heat death".[24]

As stated earlier, most Boltzmann brains have "abnormal" experiences; Feynman has pointed out that, if one knows oneself to be a typical Boltzmann brain, one does not expect "normal" observations to continue in the future.[4] In other words, in a Boltzmann-dominated Universe, most Boltzmann brains have "abnormal" experiences, but most observers with only "normal" experiences are Boltzmann brains, due to the overwhelming vastness of the population of Boltzmann brains in such a Universe.[25]

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ Carroll, Sean (29 December 2008). "Richard Feynman on Boltzmann Brains". Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ^ Sean Carroll (17 June 2019). "Sean Carroll's Mindscape". preposterousuniverse.com (Podcast). Sean Carroll. Event occurs at 1:01.47. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Brush, S. G., Nebulous Earth: A History of Modern Planetary Physics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Carroll, S. M., "Why Boltzmann brains are bad" (Ithaca, New York: arXiv, 2017).

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2002). "Introduction". Anthropic Bias: Observation Selection Effects in Science and Philosophy. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415938587.

- ^ Albrecht, Andreas; Sorbo, Lorenzo (September 2004). "Can the universe afford inflation?". Physical Review D. 70 (6): 063528. arXiv:hep-th/0405270. Bibcode:2004PhRvD..70f3528A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.70.063528. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ a b Choi, Charles Q. (13 September 2013). "Doomsday and disembodied brains? Tiny particle rules universe's fate". NBC News. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Linde, A. (2007). Sinks in the landscape, Boltzmann brains and the cosmological constant problem. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2007(01), 022.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (2008). "Big Brain Theory: Have Cosmologists Lost Theirs?". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Davenport, M., & Olum, K. D. (2010). Are there Boltzmann brains in the vacuum. arXiv preprint arXiv:1008.0808.

- ^ Mukhanov, V., Physical Foundations of Cosmology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 30.

- ^ a b Bousso, R., Freivogel, B., & Yang, I. S. (2008). Boltzmann babies in the proper time measure. Physical Review D, 77(10), 103514.

- ^ Ananthaswamy, Anil (2017). "Universes that spawn 'cosmic brains' should go on the scrapheap". New Scientist. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Grossman, Lisa (2014). "Quantum twist could kill off the multiverse". New Scientist. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Sample, Ian (8 February 2020). "Physicist Brian Greene: 'Factual information is not the right yardstick for religion'". The Observer. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Garriga, J., & Vilenkin, A. (2009). Holographic multiverse. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2009(01), 021.

- ^ "Death by Higgs rids cosmos of space brain threat". New Scientist. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Boddy, K. K., & Carroll, S. M. (2013). Can the Higgs Boson Save Us From the Menace of the Boltzmann Brains?. arXiv preprint arXiv:1308.4686.

- ^ Carlip, S. (2007). Transient observers and variable constants or repelling the invasion of the Boltzmann’s brains. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2007(06), 001.

- ^ Andrea De Simone; Alan H. Guth; Andrei Linde; Mahdiyar Noorbala; Michael P. Salem; Alexander Vilenkin (14 September 2010). "Boltzmann brains and the scale-factor cutoff measure of the multiverse". Physical Review D. 82 (6): 063520. arXiv:0808.3778. Bibcode:2010PhRvD..82f3520D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.82.063520.

- ^ Andrei Linde; Vitaly Vanchurin; Sergei Winitzki (15 January 2009). "Stationary Measure in the Multiverse". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2009 (1): 031. arXiv:0812.0005. Bibcode:2009JCAP...01..031L. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2009/01/031.

- ^ Andrei Linde; Mahdiyar Noorbala (9 September 2010). "Measure problem for eternal and non-eternal inflation". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2010 (9): 008. arXiv:1006.2170. Bibcode:2010JCAP...09..008L. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2010/09/008.

- ^ Bousso, R.; Freivogel, B. (2007). "A paradox in the global description of the multiverse". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2007 (6): 018. arXiv:hep-th/0610132. Bibcode:2007JHEP...06..018B. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2007/06/018.

- ^ Schwitzgebel, Eric (June 2017). "1% Skepticism". Noûs. pp. 271–290. doi:10.1111/nous.12129.

- ^ Dogramaci, Sinan (19 December 2019). "Does my total evidence support that I'm a Boltzmann Brain?". Philosophical Studies. doi:10.1007/s11098-019-01404-y.

Further reading

- "Disturbing Implications of a Cosmological Constant", Lisa Dyson, Matthew Kleban, and Leonard Susskind, Journal of High Energy Physics 0210 (2002) 011 (at arXiv)

- "Is Our Universe Likely to Decay within 20 Billion Years?", Don N. Page, (at arXiv)

- "Sinks in the Landscape, Boltzmann Brains, and the Cosmological Constant Problem", Andrei Linde, Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 0701 (2007) 022 (at arXiv)

- "Spooks in Space", Mason Inman, New Scientist, Volume 195, Issue 2617, 18 August 2007, pp. 26-29.

- "Big Brain Theory: Have Cosmologists Lost Theirs?", Dennis Overbye, The New York Times, 15 January 2008