Willy Fick

Willy Fick | |

|---|---|

Willy Fick in 1948 | |

| Born | February 7, 1893 |

| Died | October 3, 1967 (aged 74) |

Wilhelm Peter Hubert Fick (February 7, 1893 – October 3, 1967), called Willy Fick, was a German graphic artist born in Cologne. He belonged to the Dada movement, and in 1919 became a founding member of the artist circle called Stupid, together with Heinrich Hoerle, Angelika Hoerle (1899–1923), who was the sister of Willy Fick and the wife of Heinrich Hoerle, Anton Räderscheidt, his wife Marta Hegemann, and Franz Wilhelm Seiwert. [1] Fick was a Cologne dadaist from 1916 until 1923 and a scholarship student of Jan Thorn-Prikker at the Cologne School of Applied Arts /Kölner Werkschulen from 1928 until 1931. Duesseldorf art agent Johanna Ey represented his Weimar period works. Many works were destroyed by bombing in World War II but preserved in archival photographs in the Rheinisches Bildarchiv / Rhineland Picture Archive. Fick painted and cartooned until his death in Canada in 1967.

Early life

Wilhelm Peter Hubert Fick was the third child of cabinet maker Richard Fick of Massow, Pomerania, and Anna Kraft of Cologne, Germany. He was born in Cologne February 7, 1893. Willy's mother was the daughter of a highly placed Cologne railroad official, a loading master. While apprenticed as a cabinet maker, Willy took evening and weekend courses at the Kölner Werkschulen / Cologne School of Applied Arts, where he met artists Heinrich Hoerle and Anton Räderscheidt, who later along with him co-founded the art-political group, Stupid.[2] Fascinated by art, music and architecture, Willy subscribed to the black-and-white periodical Licht und Schatten, collected sheet music and went to the impressive 1912 exhibition titled Sonderbund westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Kunstler. Willy Fick's father was a staunch trade unionist, his young sister Angelika a budding socialist, and Willy dabbled with the anarchistic works of Mikhail Bakunin. The Fick music evenings where Willy played piano or violin with his siblings, often turned into heated political discussions.

Dadaist

Anti-war proponents such as Willy, his sister Angelika and his future brother-in-law Heinrich Hoerle felt confident the S.P.D. Social Democratic Party of Germany would not vote for war credits in 1914, but when it did, Willy Fick registered as a conscientious objector. He served in a non-combat position as a wagon driver from 1917 to 1918. He had time until 1917 to develop his art which started with anti-war linocuts mocking the sheepishness of the masses.[3] Willy's acquaintanceship circle enlarged during the war to include Otto Freundlich and Carl Oskar Jatho, both of whom had returned early from the front. From 1916 onwards Carl and Käthe Jatho ran an artist-centered anti-war group in their home where Willy met their friend Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, an artist and arts theorist with a broad circle of friends. Everyone was connected either through art, politics, war or love. Willy got into closer contact with the married artists Marta Hegemann and Anton Räderscheidt who were friends of the Hoerles. However unlike those noted, Willy Fick had full-time employment. He worked for the City of Cologne Transportation Department between 1918 and 1923 during a time when cash-strapped Germany fomented with revolt. Since Willy squeezed his art time out from work and because he was a natural buffoon, Fick became the butt of sarcastic humour during the Dada time. He appeared in the Bulletin D exhibition as an "Unknown Master from the Beginning of the 20th Century"[4] and in the Brauhaus Winter exhibition as "a vulgar dilettante". In a taped interview with Prof. Michel Sanouillet in 1967 he explained his part in these exhibition/events that mocked the established art world. He also stated that his work traveled with the Bulletin D exhibition to the Graphic Cabinet Von Bergh and Co in Düsseldorf in 1920. Fick's first works under his own name appeared in Stupid 1, the catalogue of the continuous exhibitions at the Räderscheidt apartment on Hildeboldplatz. His childlike works were in keeping with the Stupid group's intention to create a newer, better world after the Armageddon of World War I. Fairy-tale like watercolours from this period show the hope for a better world that was soon dashed by the dire post-World War I situation and by the death of his sister Angelika Hoerle who died of tuberculosis at 23 years of age.

Weimar artist

Deaths haunted Willy Fick during the inter-war period. His sister Angelika died 1923, his mother in 1927, his brother Richard in 1932, his father in 1935 and his sister Maria in 1939.[5] Deaths and the success of the Nazi party in 1933 dominated the negative iconography Fick developed. His dark works in which human simulacra float in a void and where life is played on or by a checkered board, were influenced by Surrealism, Neue Sachlichkeit and the Cologne Progressives. Although it was a personally sad and politically oppressive time, Fick's career prospered. He was a member of the Werkbund bildender Künstler/Association of Progressive Artists, exhibited at the Kölnisher Kunstverein/Cologne Art Institute, Becker and Newmann Gallery and with Johanna Ey, known as Mother Ey in Düsseldorf. Gottfried Brockmann who had been a friend of Fick's sister Angelika wrote, "Sometimes I saw pictures by him at Mrs. Ey's; they were small but very colourful. I still remember one of them clearly. It was a hot-house with steel blue and poisonous green flowers."[6] In 1927, Richard Riemerschmidt, director of the Kölner Werkschulen championed Fick so that he received a tuition-free scholarship thanks to Mayor of Cologne Konrad Adenauer. From 1928 until 1931 he studied full-time under the tutelage of Jan Thorn-Prikker, a famous glass painter and muralist. Thorn-Prikker's most significant impact on Fick's art was his lifelong interest in transparency and his love of colour experiments that looked like stained glass.

In 1932 the constellation of the short-lived "Gruppe 32" comprising glass painter Ludwig Egidius Ronig, Neue Sachlichkeit artist Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, and Fick's dada-time friends Seiwert, Räderscheidt and Hoerle, showed the mixture of Neue Sachlichkeit, glass painting and Progressive interests that blended at that time and in Fick's works as well. "Gruppe 32" had two exhibitions in Cologne and Düsseldorf before disbanding in 1933. In preparation for Fick's first solo show "Works by Willy Fick" at the City Art Museum, Düsseldorf, in March to April 1931, he had his works photographed by the Rheinisches Bildarchiv/Rhineland Picture Archive. The photo of "Morceau" shows Fick was also experimenting with sand mixed in his paints. Like Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Fick was interested in the facture that distinguished art from photography.

1931 was Fick's banner year. Picture of a Boy was reproduced in Der Querschnitt, Berlin and The Concert Nr. 1 in Cahiers d'art, Paris. Once the Nazis came into power Fick pulled back his art activities to escape notice as a former socialist and dada artist. He took the art work he'd salvaged from his sister Angelika Hoerle's apartment and hid it in the garden shed of his atelier in Vogelsang, an outskirt of Cologne. The artists represented in his cache, Max Ernst, Hoerle and Seiwert, had already been labelled degenerate artists and it was dangerous to possess their works.[7]

Fick's opposition to Fascism was expressed in his paintings of the 1930s. An example is Speaker, in which a man whose gesture resembles a distorted Nazi salute is observed by empty human silhouettes and masks. On the table in front of him is a sheet of paper inscribed with the letters ABDH, a reference to the factory code of the Heinkel He 111, a bomber which began production in 1935 in violation of the Treaty of Versailles.

Fick continued to work for the City of Cologne but ceased exhibiting. Thanks to the photos of the Rheinisches Bildarchiv / Rhineland Picture Archive, Fick's strongest works survive as black and white images. According to Fick's post-war claim for restitution, 40–45 oil paintings and over 70 watercolours and drawings were destroyed in the last years of the war, by the bombing of Cologne on October 31, 1944,[2] and by the March 1945 looting of recently released foreign labourers.

A Dadaist in Whitby

In 1945 Fick started designing hospitals and public buildings for the High Rise Division of the City of Cologne. In recognition for his success as an artist, he was given one day off per week to pursue his art. He did not actively pursue exhibition but he did show works at the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in 1959–60, at the Museum Kunstpalast /Duesseldorf Museum in 1960 and occasionally in the Aloys Faust Gallery. When his only living relative, his nephew Frank Eggert, moved to Whitby, Ontario, Fick began the first of six three-month visits; these took place between 1954 and 1967. Fick painted during his time in Whitby, applying the eyes of his European art experiences to the Canadian landscape Fick created a unique European-Canadian fusion. When he retired from the City of Cologne in 1956 Fick travelled extensively, during which time he regaled his Canadian family with illustrated letters. The letters demonstrate Fick's lifelong love of cartooning. By the mid-1960s Fick's emphysema slowed down art and travel. He managed to execute black marker sketches of scenes in Whitby and two days before his death he was installed by Professor Michel Sanouillet as an honorary member of the International Dada and Surrealism Association in recognition of his contributions to dada in Cologne. Willy Fick was buried in Whitby on October 5, 1967.[8]

Legacy

When Willy Fick paid the back rent on his deceased sister Angelika Hoerle's apartment on Bachemerstrasse in Lindenthal in 1923 he saved her works and those left behind by Max Ernst, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert and Heinrich Hoerle. When he hid nearly 300 items, he saved a time capsule of the dada time period from Nazi destruction.[9] Thanks to the family of his nephew Frank Eggert (Dr. Frank-Michael Eggert, Angelika Littlefield and spouses), the Fick-Eggert Collection at the AGO in Toronto acts as a permanent art historical resource.[10] Additionally, supporting documentation for the Fick-Eggert Collection is available through the Rheinisches Archiv Kunstlernachlässe in Bonn, Germany.[11]

When Willy Fick had his 1928–1931 works photographed by the Rheinisches Bildarchiv / Rhineland Picture Archive, he left a record of works that show the blend of styles in Cologne during the Weimar period prior to and during Nazi persecution. These photographic records inspired The Art of Dissent: Willy Fick in 2008 showing that even persecution and war cannot destroy the messages Fick's works hold for future generations.

Gallery

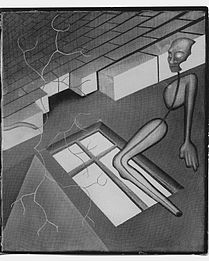

-

Morceau

-

Speaker

-

Girl in Hall

-

Grotesque

-

Chimneys

-

Diabolo

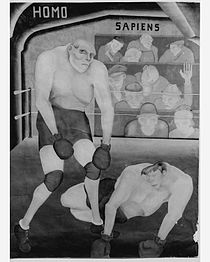

-

Sometimes called Homo Sapiens

-

Cityscape with Beech Tree

-

Nude II

-

Flowers (1950)

-

Blue Building

-

Floating Vase

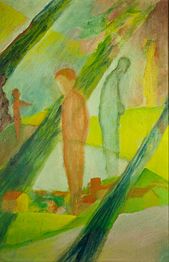

-

Abstract with Persons

-

Life's Shadow

-

Along the Beach

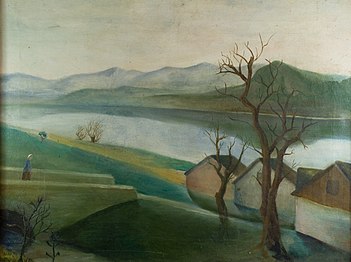

-

Along the Rhine

-

Stained Glass Abstract

-

Abstract Flowers

-

Vogelsang Atelier

-

Life's Shadow

-

Bacchanale

-

Steeplechase

-

Canadian Fisherman

-

Canadian Landscape

-

Canadian Cottage

References

- ^ Dempsey, Amy. "Art in the modern era : a guide to styles, schools & movements, 1860 to the present". Search Work. Harry N. Abrams, 2002.

- ^ a b Phillips, Carson (Spring 2010). "Willy Fick: The Metaphoric Language and Art of Dissent" (PDF). Prism. 1 (2): 39–41.

- ^ Littlefield, Angelika. "The Art of Dissent Willy Fick 1893-1967" (PDF). UJA Federation.

- ^ http://www.dada-companion.com/who-is-who.php

- ^ Teuber, Dirk "Willy Fick: A Cologne Artist of the 20s", Cologne: Wienand Verlag, 1986 ISBN 3-87909-160-9

- ^ Brockmann, Gottfried (13 August 2013). Erinnerungen an Heinz und Angelika Hoerle. Cologne Kunstverein. ISBN 9783322987075.

- ^ Phillips, Carson. "The Dissenting Art of Willy Fick" (PDF). Holocaust Centre of Toronto.

- ^ https://curatorbyday.wordpress.com/2012/12/07/willy-in-whitby/

- ^ Littlefield, A. "The Dada Period in Cologne: Selections from the Fick-Eggert Collection", Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1988 ISBN 0-919777-64-3

- ^ "Cologne Dada--Selections from the Fick-Eggert Collection". Art Gallery of Ontario.

- ^ http://www.rak-bonn.de/text/bestaende.htm