August Winnig

August Winnig | |

|---|---|

| |

| Oberpräsident of East Prussia | |

| In office 1919–1920 | |

| Generalbevollmächtigter to the Baltic Provinces | |

| In office 1917–1918 | |

| Reichskommissar for East and West Prussia | |

| In office 1917–1918 | |

| Member of the Landtag of Hamburg (SPD) | |

| In office 1913–1921 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 31 March 1878 Blankenburg |

| Died | 3 November 1956 (aged 78) Bad Nauheim |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party |

|

| Occupation | bricklayer, trade unionist, essayist. |

August Winnig (31 March 1878 – 3 November 1956[1]) was a German politician, essayist and trade unionist.

Early involved in trade unionism and editorship, Winnig held elected and public offices from 1913 to 1921 as a Social Democratic Party (SPD) member. As Generalbevollmächtigter ("Minister Plenipotentiary") for the Baltic Provinces in 1918, he signed the official recognition of the Latvian Provisional Government by the German Empire (1871–1918) that ended German claim over the region, despite being an opponent of that renouncement. He was nominated Oberpräsident of East Prussia in 1919, and pressured the Weimar Republic (1918–1933) to create an autonomous eastern State in the Baltics.

After his participation in the Kapp putsch of 1920 against the Weimar Republic, Winnig was removed from his positions by the regime and expelled from the SPD. He then became more involved in Nazi thinking and, along with Ernst Niekisch, joined the Old Social Democratic Party of Germany (ASP) to turn their theories into a political programme. The ASP failure of the 1928 German federal election led Winnig to abandon his revolutionary programme.

Initially welcoming the Nazis in 1933 as providing the "salvation of the State" from Marxism, his Lutheran convictions led Winnig to oppose the Third Reich (1933–1945) for its neo-pagan tendencies. In 1937, he wrote a best-selling essay named Europa. Gedanken eines Deutschen ("Europe. Thoughts of a German") that gives a cultural rather than racial theory of Europe, diverging from the official Nazi doctrines on race, although his book is tainted by antisemitism. Winnig writes in his autobiographies that he went from being a Nazi to a Christian conservative during the Nazi rule over Germany. He died in Bad Nauheim on 3 November 1956.

Early life and trade unionism

August Winnig was born in 1878 in Blankenburg, the youngest son from a large and poor family.[2] He attended elementary class, then learnt bricklaying. Winnig joined the Social Democratic Party (SPD) at 18-year-old in 1896 and was a member of the Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 46 from 1900 to 1902.[3]

In 1905, he became the editor of Grundstein in Hamburg, the newspaper of the Maurergewerkschaft ("Bricklayers Union") and, in 1913, the leader of the national Bauarbeiterverband ("Construction Workers Association").[1]

Elected and official positions

After acquiring the citizenship of Hamburg in 1913,[3] Winnig was elected as a SPD member of the Landtag of Hamburg and kept his siege until 1921.[1]

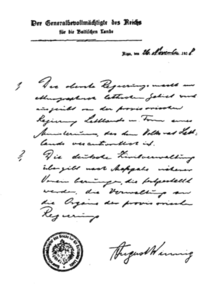

From 1917 to 1918, Winnig was appointed Reichskommissar for East and West Prussia and Generalbevollmächtigter ("Minister Plenipotentiary") to the Baltic Provinces.[3] As holder of the later position, he signed on 26 November 1918 the official recognition of the Latvian Provisional Government by the German Empire that ended German claim over the region, what is known by the Latvians as the Vinniga nota ("Winnig's note"). In order to comply with the demands of the Baltic Germans for a broader representation in the new institutions, Winnig delayed the withdrawal of German troops from Latvia and supported the formation of Freikorps in the region, with promises of land and settlement.[4]

In January 1919, after being appointed Oberpräsident of East Prussia by the Weimar Republic,[2][1] Winnig devised a plan for the creation of an autonomous State in the Baltics that would include Livonia, Kurland, Lithuania and East and West Prussia, with the false assumption that the victorious powers of WWI would concentrate their demands on Germany itself and let alone a separatist eastern State.[5] He wrote that "the East Prussian separatism was a special form of expression of national indignation", with the intention of entering into war against Poland to achieve statehood.[5]

Although Winnig and the Baltic German landowners had in mind the integrity of the Reich, they talked about a "break away from Berlin" as a mean of exerting pressure on the rest of Germany to achieve their project. For instance, Winnig mentioned at the regional conference of the East Prussian SDP the threat of an ineluctable separation if the Reich did not take necessary measures regarding East Prussia.[5] On 4 March 1920, Winnig published a memorandum on the East Prussian question and raised an abundant catalogue of demands at the East Prussia Conference on 9 March 1920, in order to obtain concessions from the Prussian and German governments for his autonomy demands.[5]

The failure of his separatist project led Winnig to participate in the failed Kapp putsch of 13 March 1920 against the Weimar Republic. He was then removed from public office by the regime and expelled from the SPD, in which he belonged to the "social-imperialistic" wing.[2]

Revolutionary period under the Weimar Republic

After his expulsion from public office by the Weimar Republic, Winnig became more involved in national revolutionary writings and is considered by Armin Mohler to be one of the most influential thinkers of the Conservative Revolution.[6]

Winnig was, along with Ernst Niekisch, co-editor of Widerstand, a magazine launched in 1926 to advocate National Bolshevism.[7][8] Winnig wrote in defence of the German workers, plunged into poverty by the post-WWI German economic situation, and denounced what he called the "Versailles Diktat". According to him, German nationalism had to embrace the workers as they were fulfilling the "German task", having replaced the role of the aristocracy.[7]

Gregor Strasser unsuccessfully tried to bring Winnig into the Nazi Party (NSDAP) during the mid-1920s.[9] In 1927, Winnig became instead a member of the Old Social Democratic Party of Germany (ASP). With the recruitments of Winnig and Nieskisch, the party intended to expand its influence outside Saxony and attract more nationalist voters. Winnig claimed that the ASP would provide the foundation for a "new Socialism", with the workers at the front of a movement for the national liberation. He theorised a Nazism based on trade unions, criticising the anti-German influence of bourgeois intellectuals on the workers' movements and writing about the "infiltration by foreign elements" (Ueberfremdung) in the leadership of the SPD.[10]

Winnig was an ASP candidate for the Reichtag during the 1928 German federal election.[1] The party suffered a crushing defeat with only 0.2% of the votes. After the ASP published a revised party programme on 12 October 1928, from which the national-revolutionary elements were removed, Niekisch and Winnig both resigned their membership and Winnig quickly abandoned their revolutionary programme.[10] He later joined the Conservative People's Party in 1930.[1]

Nazi rule and later life

Initially welcoming the Nazis in 1933 as providing the "salvation of the State" from Marxism, his Lutheran convictions led him to oppose the Third Reich for his neo-pagan tendencies. He then withdrew from politics and went into "inner emigration".[2]

In his essay Europa. Gedanken eines Deutschen ("Europe. Thoughts of a German"), published in 1937, Winnig gives a definition of Europe that diverges from the official Nazi doctrine on race, although also strongly tainted by antisemitism. Writing about "spatial ties" (Raumverbundenheit) and "cultural community" (Kulturgemeinschaft),[11] he claims that the greater nations of Europe, along with the other less powerful peoples of the continent, all come from the same superior civilisation, a legacy of Rome, the Ancient Germans and Christianity. However, he excluded Bolshevik Russia from that definition, which he believed to be the world of the Jews and the Untermenschen ("sub-humans") that only fascism could protect Europe from.[12] Printed at 80,000 copies, the book became a best-seller in Evangelical circles.[13]

Winnig wrote in his autobiographies that he went from being a Nazi to a Christian conservative during the Nazi rule over Germany.[14] He died in Bad Nauheim on 3 November 1956 at 78.[2]

See also

Works

Essays

- Der große Kampf im deutschen Baugewerbe, 1910.

- Der Burgfriede und die Arbeiterschaft (= Kriegsprobleme der Arbeiterklasse, Heft 19), 1915.

- Der Krieg und die Arbeiterinternationale. In: F. Thimme, C. Legien (Hrsg.): Die Arbeiterschaft im neuen Deutschland, 1915.

- Marx als Erlebnis. In: Glocke 4, 1 v. 4. Mai 1917, S. 138–143.

- Der Glaube an das Proletariat, 1924, new version in 1926.

- Die geschichtliche Sendung des deutschen Arbeiters. Die deutsche Außenpolitik, Lecture in Halle, 1926.

- Das Reich als Republik, 1928 (collected essays and speeches).

- Vom Proletariat zum Arbeitertum. 1930. (special issue in 1933 with an epilogue named "After three years"; several new editions until 1945).

- Der Nationalsozialismus – der Träger unserer Hoffnung. In: Neustädter Anzeigeblatt. 29 October 1932.

- Der Arbeiter im Dritten Reich, 1934.

- Arbeiter und Reich (= Erbe und Verpflichtung. 1. Auf falscher Bahn, 2. Die große Prüfung), 1937.

- Europa. Gedanken eines Deutschen, 1937.

- Der deutsche Ritterorden und seine Burgen, 1939.

Literature

- Preußischer Kommiß. Soldatengeschichten Berlin, Vorwärts-Verlag, 1910 (anti-militaristic stories; not published since they were forbidden at the time; based on Winnig's own experiences).

- Die ewig grünende Tanne, 1927 (stories illustrated by A. Paul Weber; contains the well-known story Gerdauen ist schöner, "Gerdauen is more beautiful").

- Wunderbare Welt, 1938.

- In der Höhle, 1941.

- Morgenröte, 1958 (collected narratives from various publications)

Autobiographies

- Frührot. Ein Buch von Heimat und Jugend, 1924 (first issue in 1919; dedicated to Oswald Spengler.)

- Das Buch Wanderschaft, 1941 (extension of the last part of Frührot, contains Winnig's experiences as a journeyman bricklayer).

- Der weite Weg, 1932 (reports on his career as a trade unionist until the First World War).

- Heimkehr, 1935 (reports from his activities in the Baltic States in 1918 until the Kapp Putsch; there are also earlier publications on this subject in Am Ausgang der deutschen Ostpolitik, 1921).

- Die Hand Gottes, 1938 (autobiographical experiences from a Lutheran perspective).

- Das Unbekannte, 1940 (experiences of the realm of the supernatural).

- Aus zwanzig Jahren. 1925 bis 1945, 1948 (first published in 1945 under the title Rund um Hitler).

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Kurzbiographien der Personen in den "Akten der Reichskanzlei, Weimarer Republik"". www.bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Wistrich, Robert S. (4 July 2013). Who's Who in Nazi Germany. Routledge. p. 277. ISBN 9781136413810.

- ^ a b c "Verhandlungen des Deutschen Reichstags". www.reichstag-abgeordnetendatenbank.de. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Sullivan, Charles L. (1 June 1976). "German freecorps in the Baltic, 1918–1919". Journal of Baltic Studies. 7 (2): 124–125. doi:10.1080/01629777600000131. ISSN 0162-9778.

- ^ a b c d Schattkowsky, Ralph (1 April 1994). "Separatism in the Eastern Provinces of the German Reich at the End of the First World War". Journal of Contemporary History. 29 (2): 308–316. doi:10.1177/002200949402900205. ISSN 0022-0094. S2CID 154600367.

- ^ Mohler, Armin (1950). Die konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918–1932: Grundriss ihrer Weltanschauungen (in German). Friedrich Vorwerk.

- ^ a b Woods, Roger (25 March 1996). The Conservative Revolution in the Weimar Republic. Springer. p. 78. ISBN 9780230375857.

- ^ Uwe Sauermann: Ernst Niekisch. Zwischen allen Fronten. Mit einem bio-bibliographischen Anhang von Armin Mohler. München, Berlin: Herbig, 1980, pp. 219 – 236. ISBN 3-7766-1013-1

- ^ Stachura, Peter D. (19 September 2014). The Shaping of the Nazi State (RLE Nazi Germany & Holocaust). Routledge. p. 97. ISBN 9781317621942.

- ^ a b Lapp, Benjamin. A 'National' Socialism: The Old Socialist Party of Saxony, 1926–32, in Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Apr. 1995), pp. 299–306

- ^ Lund, Joachim; Øhrgaard, Per (2008). Return to Normalcy Or a New Beginning: Concepts and Expectations for a Postwar Europe Around 1945. Copenhagen Business School Press DK. p. 130. ISBN 9788763002035.

- ^ Nurdin, Jean (2003). Le Rêve européen des penseurs allemands (1700–1950) (in French). Presses Univ. Septentrion. p. 222. ISBN 9782859397760.

- ^ Pöpping, Dagmar (5 December 2016). Kriegspfarrer an der Ostfront: Evangelische und katholische Wehrmachtseelsorge im Vernichtungskrieg 1941–1945 (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 37. ISBN 9783647557885.

- ^ Winnig, August (1951). Aus zwanzig Jahren, 1925 bis 1945 (in German). F. Wittig.

Bibliography

- Rüdiger Döhler: Ostpreußen nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Einst und Jetzt, Bd. 54 (2009), pp. 219–235.

- Klaus Grimm: Jahre deutscher Entscheidung im Baltikum. Essener Verl. Anst., Essen 1939.

- Max Kemmerich: August Winnig. Geb. 31 March 1878. Ein deutscher Sozialist. In: Militärpolitisches Forum. Neumünster, Holstein, 4 (1955), 3, pp. 6–15.

- Wilhelm Landgrebe: August Winnig. Arbeiterführer, Oberpräsident, Christ. Verl. d. St.-Johannis-Druckerei, Lahr-Dinglingen 1961.

- Jürgen Manthey: Revolution und Gegenrevolution (August Winnig und Wolfgang Kapp). In: Königsberg. Geschichte einer Weltbürgerrepublik. München 2005, pp. 554–562.

- Wilhelm Ribhegge: August Winnig. Eine historische Persönlichkeitsanalyse (= Schriftenreihe des Forschungsinstituts der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung; 99). Verlag Neue Gesellschaft, Bonn-Bad Godesberg 1973, ISBN 3-87831-147-8.

- Hannah Vogt: Der Arbeiter. Wesen und Probleme bei Friedrich Naumann, August Winnig, Ernst Jünger. 2., durchges. Auflage. Schönhütte, Göttingen-Grone 1945.

- Frank Schröder: August Winnig als Exponent deutscher Politik im Baltikum 1918/19 (= Baltische Reihe; 1). Baltische Gesellschaft in Deutschland e.V., Hamburg 1996.

- Cecilia A. Trunz: Die Autobiographien von deutschen Industriearbeitern. Univ. Diss., Freiburg im Breisgau 1935.

- Juan Baráibar López: Libros para el Führer. Inédita, Barcelona 2010, pp. 413–421.

- Reinhard Bein: Hitlers Braunschweiger Personal. DöringDruck, Braunschweig 2017, ISBN 978-3-925268-56-4, pp. 292–301.