Sanskrit inscriptions in the Malay world

A good number of Sanskrit inscriptions have been found in Malaysia and Indonesia. "Early inscriptions written in Indian languages and scripts abound in Southeast Asia. [...] The fact that southern Indian languages didn't travel eastwards along with the script further suggests that the main carriers of ideas from the southeast coast of India to the east - and the main users in Southeast Asia of religious texts written in Sanskrit and Pali - were Southeast Asians themselves. The spread of these north Indian sacred languages thus provides no specific evidence for any movements of South Asian individuals or groups to Southeast Asia.[1]

Ligor Inscription

Ligor inscription was found on the Southern Thailand Malay peninsula, at Nakhon Si Thammarat. It has been dubbed the "Ligor inscription", "Ligor" being the name given by Europeans to the region in the 16th and 17th centuries. It is written in Sanskrit[2] and bears the date of 775 AD.[3] One side of the inscription refers to the Illustrious Great Monarch (śrīmahārāja) belonging to the ‘Lord of the Mountain’ dynasty (śailendravaṁśa), which is also mentioned in four Sanskrit inscriptions from Central Java; the other side refers to the founding of several Buddhist sanctuaries by a king of Sriwijaya.[4] Sriwijaya is the name of a kingdom whose centre was located in the modern city of Palembang in South Sumatra province, Indonesia. The Ligor inscription is testimony to an expansion of Sriwijaya power to the peninsula.[5]

Kedah Inscription

An inscription in Sanskrit dated 1086 has been found in Kedah . This was left by Kulothunka Cholan I (of the Chola empire, Tamil country). This too shows the commercial contacts the Chola Empire had with Malaya.[6]

Kutai inscriptions

The oldest known inscriptions in Indonesia are those on seven stone pillars, or yupa (“sacrificial posts”), found in the eastern part of Borneo, in the area of Kutai, East Kalimantan province. They are written in the early Pallava script, in the Sanskrit language, and commemorate sacrifices held by a king called Mulawarman. Based on palaeographical grounds, they have been dated to the second half of the 4th century AD. They attest to the emergence of an Indianized state in the Indonesian archipelago prior to AD 400.

In addition to Mulawarman, the reigning king, the inscriptions mention the names of his father Aswawarman and his grandfather Kundungga. It is generally agreed that Kundungga is not a Sanskrit name, but one of native origin. The fact that his son Aswawarman is the first of the line to bear a Sanskrit name indicates that he was probably also the first to adhere to Hinduism.[7]

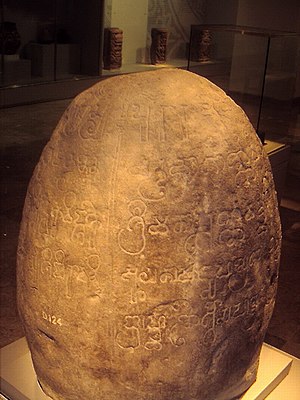

Tugu Inscription

The Tugu inscription is one of the Tarumanagara inscriptions discovered in Batutumbuh hamlet, Tugu village, Koja, North Jakarta, in Indonesia. The inscription contains information about hydraulic projects; the irrigation and water drainage project of the Candrabaga river by the order of Rajadirajaguru, and also the water project of the Gomati river by the order of King Purnawarman in the 22nd year of his reign. The digging project to straighten and widen the river was conducted in order to avoid flooding in the wet season, and as an irrigation project during the dry season.

The Tugu inscription was written in Pallawa script arranged in the form of Sanskrit Sloka with Anustubh metrum, consisting of five lines that run around the surface of the stone. Just like other inscriptions from the Tarumanagara kingdom, the Tugu inscriptions do not mention the date of the edict. The date of the inscriptions was estimated and analyzed according to paleographic study which concluded that the inscriptions originated from the mid 5th century. The script of the Tugu inscription and the Cidanghyang inscription bear striking similarity, such as the script "citralaikha" written as "citralekha", leading to the assumption that the writer of these inscriptions was the same person.

The Tugu inscription is the longest Tarumanagara inscription pronounced by edict of Sri Maharaja Purnawarman. The inscription was made during the 22nd year of his reign, to commemorate the completion of the canals of the Gomati and Candrabhaga rivers. On the inscription there is an image of a staff crowned with Trisula straight to mark the separation between the beginning and the end of each sentence.

See also

- Tamil inscriptions in the Malay world

- Symbolic usage of Sanskrit

- Indianisation

- Sanskritisation

- Indosphere

- Greater India

Notes

References

- ^ Jan Wisseman Christie, "The Medieval Tamil-language Inscriptions in Southeast Asia and China", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 29, No. 02, September 1998, pp 239-268

- ^ Niranjan Prasad Chakravarti and Bijan Raj Chatterjee, An Outline of Indo-Javanese History, Calcutta: Greater India Society, 1926

- ^ O. W. Wolters, “Tambralinga”, in Classical civilisations of South East Asia: an anthology of articles published in the Bulletin of SOAS (Vladimir Braginsky ed.), RoutledgeCurzon, 2002, 0-7007-1410-3, p. 588

- ^ Pierre-Yves Manguin, “Srivijaya, An Introduction”, Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009

- ^ Leonard Y. Andaya, Leaves of the same tree: trade and ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka, University of Hawaii Press, 2008, p. 149

- ^ Arokiaswamy, Celine W.M. (2000). Tamil Influences in Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Manila s.n. pp. 37, 38, & 41.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ S. Supomo, "Chapter 15. Indic Transformation: The Sanskritization of Jawa and the Javanization of the Bharata in Peter S. Bellwood, James J. Fox, Darrell T. Tryon (eds.), The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, Australian National University, 1995