Fakhr al-Din II

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Arabic. (April 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

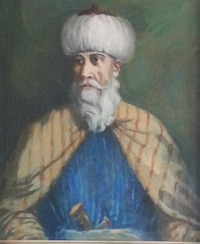

| Fakhr-al-Din II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fakhr-al-Din II | |||||

| Emir of Lebanon | |||||

| Reign | 1591 – 13 April 1635 | ||||

| Predecessor | Qurqumaz | ||||

| Successor | Mulhim | ||||

| Born | August 6, 1572 Baakleen, Mount Lebanon Emirate (Ottoman Empire) | ||||

| Died | April 13, 1635 (aged 62) Constantinople, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Issue | Ali Beg Husayn | ||||

| |||||

| House | Ma'an | ||||

| Father | Korkmaz Ma'an | ||||

| Mother | Sit Nasab Tanukhi | ||||

| Religion | Druze | ||||

Fakhr-al-Din ibn Maan (August 6, 1572 – April 13, 1635) (Arabic: الامير فخر الدين بن معن), also known as Fakhreddine and Fakhr-ad-Din II,[1] was a Druze Ma'an Emir and an early leader of the Mount Lebanon Emirate, a self-governed area subject to the Ottoman Empire.

He fought other Lebanese families to unite the people of Lebanon and seek independence from the Ottoman Empire. His rule was characterized by economic and cultural prosperity. Some consider him the first "Man of Lebanon" to seek the sovereignty of modern-day Lebanon, others see the claim as anachronistic as his aims were more dynastic than national. However, the Ottomans eventually tired of this troublesome vassal and, on 13 April 1635, Sultan Murad IV had him executed together with his brother and son.[2]

Life and reign

Fakhr al-Din was born on August 6, 1572, in Baakline to Qurqumaz (Arabic: الامير قرقماز بن معن), the Emir of Lebanon and Sit Nasab (Arabic: الست نسب) of the Druze Ma'an family. Fakr-al-Din came into power in 1591 at the age of 19 when his father was killed by the rival Sayfi clan which ruled northern Lebanon from the port city of Tripoli. Following the assassination of his father he was motivated by revenge and the expansion of his family's territory. In order to fulfill his ambition, Fakr-al-Din maintained good relations with the Ottoman authorities. Through his political connections with Ottoman pashas he managed to extend his rule to Beirut, Sidon, northern districts of Mount Lebanon and the fertile Beqaa Valley. By 1607, he controlled most of the modern state of Lebanon and northern Palestine.[3]

Alliance with Tuscany

In order to cement his position, Fakhr al-Din forged an alliance with the Italian Grand Duchy of Tuscany in 1608.[4] The Medici offered guns and assistance to Fakr-al-Din's fortifications in exchange for gaining access to the lucrative Levantine trade.[3] Fakhr al-Din's ambitions, popularity and unauthorized foreign contacts alarmed the Ottomans who authorized Hafiz Ahmed Pasha, governor of Damascus, to mount an attack on Lebanon in 1613 in order to reduce Fakhr al-Din's growing power. Faced with Hafiz's army of 50,000 men, Fakhr al-Din chose exile in Tuscany, leaving affairs in the hands of his brother Yunis and his son Ali Beg. They succeeded in maintaining most of the forts such as in Banias (Subayba) and in Niha which were a mainstay of Fakhr al-Din's power. Before leaving, Fakhr al-Din paid his standing army of soqbans (mercenaries) two years wages in order to secure their loyalty.[5]

Hosted in Tuscany by the Medici Family, Fakhr al-Din was welcomed by the grand duke Cosimo II, who was his host and sponsor for the two years he spent at the court of the Medici. He spent a further three years as guest of the Spanish Viceroy of Sicily and then Naples, Pedro Téllez-Girón. Fakhr al-Din had wished to enlist Tuscan or other European assistance in a "Crusade" to free his homeland from Ottoman domination,[6] but was met with a refusal as Tuscany was unable to afford such an expedition. The emir eventually gave up the idea, realizing that Europe was more interested in trade with the Ottomans than in taking back the Holy Land. His stay nevertheless allowed him to witness Europe's cultural revival in the 17th century, and bring back some Renaissance ideas and architectural features.[7]

Return to rule

By 1618, political changes in the Ottoman sultanate had resulted in the removal of many of Fakhr al-Din's enemies from power, allowing his return to Lebanon, whereupon he was able quickly to reunite all the lands of Lebanon beyond the boundaries of its mountains; and having revenge from Emir Yusuf Pasha ibn Siyfa, attacking his stronghold in Akkar, destroying his palaces and taking control of his lands, and regaining the territories he had to give up in 1613 in Sidon, Tripoli, Beqaa among others. Under his rule, printing presses were introduced and Jesuit priests and Catholic nuns encouraged to open schools throughout the land. Sidon became a major trading center as European nations such as France and Genoa constructed commercial buildings.[8]

Battle of Anjar

In 1623, the prince angered the Ottomans by refusing to allow an army on its way back from the Persian front to winter in the Beqaa. This (and instigation by the powerful Janissariy garrison in Damascus) led Mustafa Pasha, Governor of Damascus, to launch an attack against him, resulting in the battle at Anjar where the Emir's forces although outnumbered managed to capture the Pasha and secure the Lebanese prince and his allies a much needed military victory. By 1628/9, Kuchuk Ahmed Pasha of Albanian origin who used to work as a tax-collector for Fakhr al-Din in southern Lebanon, but later sacked due to financial defalcations, was then named as a governor of Damascus, and he was shortly recalled to Kütahya to suppress the rebels in Anatolia.[9]

By 1629, Fakhr al-Din had extended his territory into the Syrian desert and northwards towards Anatolia. However, as time passed, the Ottomans grew increasingly uncomfortable with the Emir's increasing powers and extended relations with Europe. In 1631, he once again denied an Ottoman army to winter in his territory which resulted in the Ottomans determination to remove him from power.[3] The governor of Damascus, Kucuk Ahmad Pasha was dispatched at the head of an army to capture Fakhr al-Din.[2]

As the Ottoman army approached, Unitarien and Christian leaders refused to join Fakhr al-Din's call for battle and left him and his family to their own devices. The fugitive emir took refuge deep in the Druze mountain heartlands of Chouf but was captured when the Ottoman generals started fires to smoke him out of his hiding place.[3]

Death

Fakhr al-Din was taken to Constantinople and kept in the Yedikule (Seven Towers) prison for two years. He was executed on 13 April 1635 along with his brother Yunus and his son Ali Beg.[3]

After his death, his Druze nephew Mulhim ruled the Shouf heartland of Fakhr al-Din's former domains until his death in 1658 after which a power struggle erupted between his sons which was eventually won by Ahmad, who ruled until 1697. After his death, the Shihab family succeeded the Ma'ans as "Emirs of Mount Lebanon".[10]

References

- ^ Salibi, Kamal (July 1973). "The Secret of the House of Ma'n". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 4 (3): 272–287. doi:10.1017/S0020743800031469. JSTOR 162160.

- ^ a b Syria and Bilad al-Sham under Ottoman rule : essays in honour of Abdul Karim Rafeq. Brill. 12 July 2010. p. 22. ISBN 978-9004191044.

- ^ a b c d e The Arabs : a history (1st ed.). Allen Lane. 5 November 2009. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0141939629.

- ^ Carali, P. Paolo (Qar’ali, Father Bulus) (1936). Fakhr ad-Dīn II, principe del Libano e la Corte di Toscana: 1605 - 1635. Reale Accademia d'Italia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Renaissance Emir. Interlink Books. 30 July 2014. ISBN 978-1623710538.

- ^ Charles Winslow (4 October 2003). Lebanon: War and Politics in a Fragmented Society. Routledge. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-203-21739-9.

- ^ The best European source for information about the Emir's stay there is the works of Palo Carali (Boulos Car'ali): Carali, P. Paolo (Qar’ali, Father Bulus): Fakhr ad-Din II Principe del Libano e la Corte di Toscana 1605-1635 (Rome, Reale Accademia d’Italia, 1936) (2 Vol.); Fakhr ad-din al-Ma’ni ath-thani, hakim lubnan (Jdeidet al-matn, Dar lahd khater, 1992); "Soggiorno de Fakhr ad-din II al-Ma’ni in Toscana, Sicilia e Napoli e la sua visita a Malta (1613-1618)", in Annali del Istituto Superiore Orientale di Napoli, Vol VIII no. 4 (September, 1936) pp. 15-60

- ^ Harris, William (2012). A History 600-2011. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016: Oxford University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-19-021783-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1980). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition: Supplement, Teile 1-2. Brill Archive. p. 49. ISBN 9789004061675.

- ^ Abdul Rahim Abu Husayn (1985). Provincial Leaderships in Syria, 1575-1650. American University of Beirut. ISBN 9780815660729.

Further reading

- A. Hourani, New Documents on the History of Mount Lebanon and Arabistan in the 10th and 11th Centuries H. pp. 918–942 (Beirut: 2010)

- T. J. Gorton, Renaissance Emir: a Druze Warlord at the Court of the Medici (London: Quartet Books, 2013)

- R. Cuffaro, "Fakhr ad-Din II alla corte dei Medici (1613-1615). Collezionismo, architettura e ars topiaria tra Firenze e Beirut", in: Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenschaft, 2010

- K. El Bibas, "L'Emiro e il Granduca, La vicenda dell’emiro Fakhr ad-Din II del Libano nel contesto delle relazioni fra la Toscana e l’Oriente", (Firenze, Le Lettere, 2010)