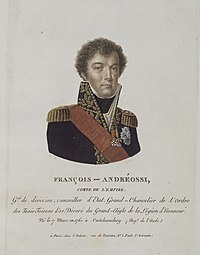

Antoine-François Andréossy

Antoine-François Andréossy | |

|---|---|

S.E. M. le comte Andréossy | |

| Nickname(s) | Italian: Antonio Andreossi |

| Born | 6 March 1761[1] Castelnaudary |

| Died | 10 September 1828 (aged 67)[1] Montauban |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | French Army |

| Rank | General |

| Battles / wars | |

| Relations | Dr. François Andréossi (great-grandfather) |

| Other work | Ambassador to Great Britain; Ambassador to Austrian Empire; Ambassador to Ottoman Empire; Deputy of the French Parliament |

Antoine-François, comte Andréossy (6 March 1761 – 10 September 1828)[1] was a Franco-Italian nobleman, who served as a French Army artillery general, diplomat and parliamentarian.

Biography

[edit]Born at Castelnaudary in Aude, scion of an ancient Italian minor noble family from Lucca, he was a great-grandson of the celebrated civil engineer and architect of the Canal du Midi, François Andréossy (1633-1688).[2][3]

An outstanding officer cadet at the Metz School of Artillery,[2] Andréossy was commissioned in the Régiment Royal-Artillerie in 1781, seeing action in the Dutch Civil War (1787);[citation needed] he was promoted as Captain in 1788.[2]

On the outbreak of the Revolution he adopted its principles.[2] At the start of the Revolutionary Wars he saw active service on the Rhine in 1794 and in Italy in 1795, and in the campaign of 1796–1797[2] under Napoleon Bonaparte on engineer duties, commanding the bridging train of the French Army of Italy after June 1796, and fought with distinction at the Battle of the Bridge of Arcole and the Siege of Mantua.[citation needed].

He was promoted to brigadier general in 1798, in which year he accompanied Bonaparte to Egypt. He served in the Egyptian Campaign with distinction—he commanded the French flotilla on the Nile, before serving as Marshal Louis-Alexandre Berthier's aide-de-camp in Syria[citation needed]—and was selected as one of Napoleon's companions on his return to Europe.[2]

Andréossy took part in the coup d'état of the 18 Brumaire, and on 6 January 1800 was made general of Général de division. Of particular importance was his term of office as ambassador to Great Britain during the short peace which followed the treaties of Amiens and Lunéville. It had been shown (Coquille, Napoleon and England, 1904) that Andréossy repeatedly warned Napoleon that the British government desired to maintain peace but must be treated with consideration. His advice, however, was disregarded. When Napoleon became emperor he made Andréossy inspector-general of artillery,[2] a Chevalier de l'Empire (1803) and on 24 February 1809,[citation needed] Count of the First French Empire.[2]

In the war of 1805 Andréossy was employed on the headquarters staff of Napoleon. From 1808 to 1809 he was French ambassador at Vienna, where he displayed a hostility to Austria which was in marked contrast to his friendliness to England in 1802–1803. In the war of 1809, Andréossy was military governor of Vienna during the French occupation.

In 1812 he was sent by Napoleon as Ambassador to The Porte in Constantinople, where he carried on the policy initiated by Sébastiani. Shortly after his arrival, he was implicated in the death of the senior Greek official Panagios Mourousi, who deputised for his brother Demetrious as Dragoman of the Porte. After France began its invasion of Russia in June 1812, Andréossy declared that he could not treat with the Ottoman government through an interpreter attached to the Russian interest. Mourousi was first dismissed and then taken under guard to the Porte, where he was beheaded.[4] In 1814 Andréossy was recalled from Contantinople by Louis XVIII.

Andréossy then retired into private life, until the escape of Napoleon from Elba once again called him forth.[2] He accepted the office of head of the War Department. After the defeat at Waterloo and the abdication of Napoleon, he was one of the five commissioners sent to negotiate with the Coalition powers, on which occasion he gave his consent to the recall of Louis XVIII.[5]

Andréossy held high administrative office under the Bourbon Restoration, including Chief of General Staff and Councillor of State.[citation needed] He was awarded honorary fellowship of the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques in 1826,[2][6] He was later elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1827, representing Aude as Deputy until his death in 1828.[2][7] His name is inscribed in his memory under the Arc de Triomphe.[8]

Works

[edit]Andréossy's numerous works included the following:[2]

- on artillery (with which arm he was most intimately connected throughout his military career):

- Quelques idées relatives à l'usage de l'artillerie dans l'attaque et ... la défense des places (Metz);

- Essai sur le tir des projectiles creux (Paris, 1826);

- on military history:

- Campagne sur le Main el la Rednitz de l'armée gallo-batave (Paris, 1802);

- Opérations des pontonniers en Italie . . . 1795-1796 (Paris, 1843).

Andréossy also wrote scientific memoirs on the mouth of the Black Sea (1818-1819); on certain Egyptian lakes (during his stay in Egypt); and in particular the history of the Languedoc Canal (Histoire du canal du Midi, 2nd ed., Paris, 1804), the chief credit of which he claimed for his ancestor. Andréossy died at Montauban in 1828.[2]

Family

[edit]On 15 September 1810, Andréossy married Marie-Florimonde-Stéphanie de Faÿ, daughter of Charles, marquis de La Tour-Maubourg. Their only son, Étienne-Auguste (1811-1835), succeeded as the 2nd Count Andréossy in 1828 and was also a promising French Army officer but died unmarried in a riding accident, when the title became extinct;[9] the Dowager Countess Stéphanie died on 21 February 1868 in Haute-Garonne.

Honours and titles

[edit]Titles

[edit]Honours

[edit] – Grand-croix, Order of Saint Louis

– Grand-croix, Order of Saint Louis – Grand-officier, Ordre de la Légion d'honneur

– Grand-officier, Ordre de la Légion d'honneur – Chevalier, Order of Malta

– Chevalier, Order of Malta – Commandeur, Orders of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and St Lazarus

– Commandeur, Orders of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and St Lazarus – Grand-chancelier, Order of the Golden Fleece

– Grand-chancelier, Order of the Golden Fleece

See also

[edit]- French Revolutionary Wars: campaigns of 1798

- List of Ambassadors of France to the United Kingdom

- Armorial of Counts of the French Empire (in French)

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c "Antoine-François Andréossy (1761-1828)". Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Chisholm 1911, p. 971.

- ^ Lycée François Andréossy 2015.

- ^ Hart, Patrick; Kennedy, Valerie; and Petherbridge, Dora (Eds.) (2020), Henrietta Liston's Travels: The Turkish Journals, 1812–1820, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 140–141

- ^ Thomas 1892, p. 125.

- ^ ASMP.

- ^ Assemblée nationale 2015.

- ^ Jensen 2014.

- ^ Salle des inventaires virtuelle.

References

[edit]- "Antoine, François Andréossy (1761 - 1828)", Mandats à l'Assemblée nationale ou à la Chambre des députés (17/11/1827 - 16/05/1830) (in French), Assemblée nationale, 2015, archived from the original on 23 September 2015, retrieved 25 April 2015

- "ASMP: Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques", ASMP (in French), archived from the original on 14 January 2013, retrieved 28 April 2015

- "C VILLANI à l'IUT de Nîmes le jeudi 7 Mai 2015", Lycée François Andréossy (in French), 1 April 2015, retrieved 28 April 2015

- "Salle des inventaires virtuelle", Salle des inventaires virtuelle (in French), retrieved 28 April 2015

- Jensen, Nathan D. (May 2014), "Antoine-François Andreossy", Arc de Triomphe, retrieved 28 April 2015

Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Andréossy, Antoine-François". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 971. Endnotes:

- Marion, Notice nécrologique sur le Lt.-Général Comte Andréossy.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Thomas, Joseph (1892), Universal pronouncing dictionary of biography and mythology (Aa, van der – Hyperius), vol. 1, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, p. 125

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Thomas, Joseph (1892), Universal pronouncing dictionary of biography and mythology (Aa, van der – Hyperius), vol. 1, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, p. 125

Further reading

[edit]- Chandler, David, Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars[full citation needed]

- "Les personnages", Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire (in French), 26 January 2007, archived from the original on 15 January 2015, retrieved 28 April 2015

External links

[edit]- 1761 births

- 1828 deaths

- 19th-century French diplomats

- Ambassadors of France to Austria

- Ambassadors of France to Great Britain

- Ambassadors of France to the Ottoman Empire

- Counts of the First French Empire

- French generals

- French people of Italian descent

- French Republican military leaders of the French Revolutionary Wars

- 19th-century Italian nobility

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Knights of Malta

- Knights of the Order of Saint Louis

- Recipients of the Legion of Honour

- Members of the Chamber of Deputies of the Bourbon Restoration

- Members of the Chamber of Peers of the Hundred Days

- Members of the Conseil d'État (France)

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe

- Peace commissioners of the French Provisional Government of 1815

- People from Castelnaudary