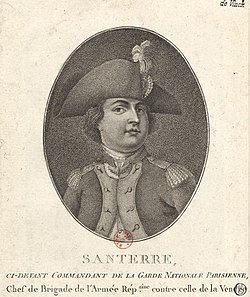

Antoine Joseph Santerre

Antoine Joseph Santerre (16 March 1752 in Paris – 6 February 1809) was a businessman and general during the French Revolution.

Early life

The Santerre family moved from Saint-Michel-en-Thiérache to Paris in 1747 where they purchased a brewery known as the Brasserie de la Magdeleine. Antoine Santerre married his third cousin Marie Claire Santerre, daughter of a wealthy bourgeois brewer, Jean François Santerre, from the Cambrai in March 1748. The couple had six children, Antoine Joseph being the 3rd. The others were Marguerite, born in 1750; Jean Baptiste, born in 1751; Armand Théodore, born in 1753; followed by François and Claire. The future general's father died in 1770, his mother just months later. His elder brother and sister, Marguerite and Jean Baptiste took charge of the household and family business, helping their mother raise the younger children, they never married. Armand Théodore went into the sugar business, and owned a factory in Essonnes, the other members of the family remained in the brewery business. François, known as François Santerre de la Fontinelle, had breweries in Sèvres, Chaville and Paris and Claire, the youngest, married a lawyer.[1] Antoine Joseph was sent to school at the collèges des Grassins, followed by history and physics under M.M. Brisson and the abbot Nollet. His interest in physics led advances in beer production that pushed breweries out of their infancy.[2] In 1770 Antoine Joseph was emancipated, and 2 years later, with his inheritance he purchased with his brother François Mr. Acloque's brewery at 232 Faubourg St. Antoine for 65,000 French Francs. In that same year he married his childhood sweetheart, the daughter of his neighbour, Monsieur Francois, another wealthy brewer. Antoine Joseph was 20 years old and Marie François was sixteen. Marie died the following year from an infection derived from a fall during her 7th month of pregnancy. Years later Antoine Joseph married Marie Adèlaïde Deleinte with whom he had three children, Augustin, Alexandre and Theodore.

Military life

His generosity won great popularity in the Faubourg St. Antoine. When the French Revolution erupted in 1789, he was given command of a battalion of the Parisian National Guard and participated in the storming of the Bastille. After the Champ de Mars Massacre on 17 July 1791, a warrant was issued for his arrest and Santerre went into hiding. He emerged again the following year to lead the people of the Faubourg St. Antoine, the eastern units, in the assault on the Tuileries Palace by the Paris mob, which overwhelmed and massacred the Swiss Guard as the royal family fled through the gardens and took refuge with the Legislative Assembly. Louis XVI was officially removed as king soon after.

Santerre was appointed by the National Convention to serve as the jailer of the former king. He notified Louis that the motion had passed for his execution, and the next day, at eight o'clock on a 21 January morning, Santerre arrived at the convicted man's room and said, "Monsieur, it's time to go". He escorted Louis XVI through the some eighty-thousand armed men and countless citizens down the streets of Paris to the guillotine. There are differing accounts of his conduct at the execution itself. According to some, he ordered a drum roll half way through the king's speech in order to drown out his voice. Others say that it was actually General J.F. Berruyer – the man in command of the execution – who ordered the drum roll, and that Santerre only relayed the order. Santerre's family maintained, however, that he actually silenced the drums so that Louis could speak to the people.

Santerre was promoted to General of a division of the Parisian National Guard in July 1793. When the revolts broke out in the Vendée, Santerre took command of a force sent in to put a stop to the rebellions. He was not as successful as a military commander in the field; his first military operation saw the defeat of the Republican forces at Saumur. After the battle, reports circulated that Santerre himself had been killed; the Royalists even composed a humorous epitaph about his death. Nor was Santerre popular among the sans-culottes he commanded. Wounded soldiers returning to Paris reported that he was living in Oriental luxury and complained that their defeat was due either to his treason or his incompetence. Some demanded that he be relieved of his command or even sent to the guillotine. On the other hand, Santerre was not in supreme command, and not considered responsible for the outcome of the war.

In October, Santerre returned to Paris, where his popularity in the Faubourg St. Antoine was undiminished. Nevertheless, his report on this expedition, in which he drew attention to the plight of the Republican army in the Vendée, aroused suspicion. Accused of being a Royalist due to his lack of glory during the battles in the Vendée, he was arrested in April 1794 and was imprisoned until the fall of Robespierre. Upon his release, he resigned his command and attempted to return to business, but his brewery was ruined. He died in poverty in Paris on 6 February 1809.

References

- David Andress, The Terror: the Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France (2005).

- Lynn Hunt, Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution (1984).

- David Jordan, The King’s Trial: Louis XVI vs the French Revolution (1979).

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Santerre, Antoine Joseph". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.