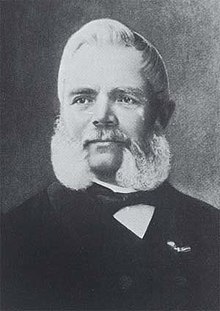

Antoni Patek

Antoni Patek | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Antoni Norbert Patek June 14, 1812 |

| Died | March 1, 1877 (aged 64) |

| Resting place | Cemetery of Châtelaine |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Occupation(s) | watchmaker, political activist |

| Known for | founding Patek Philippe & Co. |

| Awards | Virtuti Militari (1831) |

Antoni Norbert Patek (French: Antoine Norbert de Patek; 14 June 1812 – 1 March 1877) was a Polish pioneer in watchmaking and the creator of Swiss watchmaker company Patek Philippe & Co., as well as a Polish independence fighter and political activist.[1]

Early life

[edit]

Antoni Norbert Patek de Prawdzic was born in 1812 to a prominent family in Piaski Szlacheckie near Lublin in the Duchy of Warsaw to Anna née Piasecka and Joachim Patek of Prawdzic coat of arms.[2] At the age of 10, Patek moved with his parents to Warsaw where his father died on 7 April 1828.[3]

On 1 March 1828, 16-year-old Patek joined the Polish 1st Mounted Rifles Regiment. He fought in the Polish November Uprising against Russian rule during which he was wounded twice. On 27 February 1831, for his heroic attitude Patek was promoted the second lieutenant of the "1 August" brigade, and on 3 October the same year decorated with Virtuti Militari Golden Cross. After the downfall of the uprising – like many other officers and soldiers of Polish Army – he had to emigrate.[3]

In 1832 he was engaged by general Józef Bem in organising an evacuation route for Polish insurgents through Prussia to France. He was charged with a command over a staging point in Bamberg near Munich (one of five staging points on the insurgents' evacuation route). After terminating the evacuation, Patek settled in France, firstly in Cahors, then in Amiens where he worked as a type-setter.[2]

Two years later an unfavourable decree issued by the French government under pressure from the Russian embassy, forced many former insurgents to resettle in Switzerland. Patek tried his hand at many trades, including trading with liquors and wines in Versoix near Geneva. For some time Patek attended painting courses given by the famous Swiss painter and engraver Alexandre Calame. During his studies, Patek also traveled to Paris where he remained for several months. Around this time, he was befriended by the Moreau family of Versoix, at whose home he would meet his future wife. They probably encouraged him in a new activity – the trade in expensive pocket watches, which were decorated by the goldsmiths, engravers, enamellers and miniaturists of the time. He thus started by buying movements of watches which he got to the Geneva watchmakers already known for the quality of their products and, under his direction, made them furnish with cases. From the very start, he attached highest importance to the quality and the artistic value of work and rather quickly managed to find the market where such creations of exceptional quality were highly appreciated.[2][3]

On 20 July 1839 in Versoix, Patek married Marie Adélaïde Elisabeth Thomasine Dénizart, a daughter of a French tradesman Louis Charles Dénizart from Turin, and of his wife Marie Jeanne Adélaïde Elisabeth, née Devimes. Antoni and Marie de Patek had three children. The first one, Boleslas Joseph Alexandre Thomas (Bolesław Józef Aleksander Tomasz), born on 16 June 1841, died on 18 September the same year. The two others were born much later, when Marie de Patek already was respectively 39 and 41 year old: a son, Leon Mecislas Vincent (Leon Mieczysław Wincenty), 19 July 1857, and one girl, Marie Edwige (Maria Jadwiga), 23 October 1859.[3]

Patek, Czapek & Co. (1839–1845)

[edit]

On 1 May 1839, in Geneva, Antoni Patek together with another Polish immigrant - Franciszek Czapek (who in fact was of Czech descent), the gifted Warsaw watchmaker established their manufacture producing watches. The company was financially supported also by its first workers, among others Polish watchmakers: Wawrzyniec Gostkowski, Wincenty Gostkowski, and Władysław Bandurski. The first pocket watches were produced on individual orders. Primarily the young firm's artistic production reflected themes from Polish history and culture, such as portraits of revolutionary heroes, 10th and 12th centuries’ legends, and the cult of the Polish Black Madonna of Częstochowa.[2][3][4]

The small company Patek, Czapek & Co, which employed a half-dozen of workmen, produced approximately two hundred watches of quality per annum. The few preserved specimens make it possible to note the degree of perfection of these first watches, result of a successful union between artistic research and the technical skill.[5]

Among the collection of the Patek Philippe Museum are watches presenting the coat of arms of Princess Zubów (see picture [2]) from 1845 and the portraits of Polish general Tadeusz Kościuszko, and Polish prince and marchal of France Józef Poniatowski (see picture [3]) from 1948.

Patek & Co. (1845–1851)

[edit]Increasing disagreement between Patek and Czapek obliged the latter to withdraw. In 1851 Czapek established Czapek & Co. where he produced watches until 1869. On 15 May 1845 the place vacated by Czapek was filled by the 30-year-old French watchmaker Adrien Philippe, who in 1842 invented the key-less winding mechanism.[2][4][6][7]

Patek Philippe & Co.

[edit]

On 1 January 1851 Patek & Co. transformed into Patek Philippe & Co. The company started mass production of pocket watches.[2][6]

Both co-owners recognised perfection as their ideal, and the company gained its success thanks to principles that Antoni Patek left to his descendants:

- the quality of produced watches maintained on the highest possible level,

- the ability of implementing new inventions and constructive solutions.[2]

The "Queen Victoria" (see picture [4]) open-face keyless-winding watch was presented to Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom during the Great Exhibition of London at Hyde Park (Crystal Palace), on 18 August 1851.[8]

In 1868, Patek Philippe made their first wristwatch, which was sold on 13 November 1876 to the Hungarian Countess Koscowicz.[9] They have also pioneered in perpetual calendar, chronograph and minute repeater in watches.[10]

Looking for trade contacts Patek travelled among others to England (1847), USA (1854), and Russia (1858).[2]

After Patek's death the company changed its owners several times; since 1929 Patek Philippe & Co. has been owned by the Stern family, but kept its original name. Patek Philippe & Co. issues collectable watches every year, and till today has remained a coveted luxury brand. Patek Philippe & Co. is the only Geneva watch manufacturer honoured with the Geneva seal. Of all the movements bearing the Geneva Seal distinction, 95% are Patek Philippe & Co. timepieces. The company does not cease in its efforts to innovate its products. Patek Philippe & Co. has been awarded more than 70 patents, since implementing in 1845 the stem winding system. The 20 most expensive wristwatches sold at auction are all from Patek Philippe & Co. The Patek Philippe Henry Graves Supercomplication watch made in 1933 holds the world record for the most expensive watch—sold at auction in 1999 for more than $11 million.[11]

The Sky Moon Tourbillon Ref 5002 is currently the world most complex complication timepiece. At present only 3 pieces are produced a year. Owners of these watches are selected by Patek Co as they are highly sought after. They are sold primarily to collectors rather than traders so as to avoid the flipping of watches for profits.

Political life

[edit]

In 1843, Patek was naturalized in Geneva and thus acquired Swiss nationality. However, he did not cease his political activity of a Polish emigrant and did not stop in his efforts to bring his assistance to the refugees. Thus, in 1838, he supported the initiative of a group of Polish emigrants for the establishment of the "Polish Foundation", an organization of mutual aid which was founded the following year and of which he became the treasurer and one of the most active members. In May 1844, he took part in the installation of a Polish Library with a salon of lecture in Geneva. Persuaded of the need for a centralization of the organizations of Polish emigrants, he recommended to the Poles residing in Geneva to collaborate with the commission of the "Funds of Polish Emigration" and the Polish Library in Paris. In the years 1843, 1845 and 1847 he requested the support of prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski for this society. On 18 May 1846, Patek adhered to the Polish Democratic Society of Lyon and, during the Spring of Nations in 1848, he went secretly to Frankfurt am Main to propose there, at the time of the meeting on 6 March of Dozór Polski, the convocation of the Polish Parliament in exile.[3]

The political activities of Patek during the January Uprising in 1863 [12] were described by Julian Aleksander Bałaszewicz, writing under the pseudonym of Albert Potocki. After the crushing of the insurrection, Patek brought his assistance to the refugees arriving to Geneva and maintained the relations with the Congregation of the Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ, (Polish: Zmartwychwstańcy), in Paris. Thereafter, the pope Pius IX conferred on Patek the title of a count, in recognition of the services rendered as well as an active Catholic, as within the community of the Polish emigrants. Unfortunately, the files of the Vatican do not preserve documents providing information about the date and the nature of this distinction.[2][3]

Antoni Patek died in Geneva and was buried in a local cemetery in Chatelaine.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Agnieszka Warnke (20 December 2020). "Antoni Patek – A Timeless Genius". culture.pl. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Marcin Pietrzak. "HISTORIA ZEGARMISTRZOSTWA - OSOBY POLSKIEGO ZEGARMISTRZOSTWA - Klub Miłośników Zegarów i Zegarków". Zegarkiclub.pl. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Swiss Watch Authority". WorldTempus. Archived from the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ^ a b "Theme". Patekmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-21. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ^ "Swiss Watch Authority". WorldTempus. Archived from the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ^ a b "Swiss Watch Authority". WorldTempus. Archived from the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ^ "Precyzja i elegancja". Archived from the original on 2005-09-28. Retrieved 2005-12-09.

- ^ "Watch Detail". Patekmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ^ "Watch Detail". Patekmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-21. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ^ "Patek Philippe: Patents". Archived from the original on 2006-03-14. Retrieved 2005-12-10.

- ^ [1] Archived January 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dąbrowski, Krysztof (1995). Polacy nad Lemanem w XIX wieku. Wydawn. Polskiego Tow. Wydawców Książek. p. 88.

- (in French) Page de la marque Patek-Philippe Archived 2013-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- The Patek Philippe Museum

- (in Polish) Biography of Antoni Patek

- (in Polish) "Precyzja i Elegancja" in "Młody Technik" monthly

- (in French) Biography of Antoni Patek Archived 2008-10-12 at the Wayback Machine

- (in French) Biography of Jean-Adrien Philippe Archived 2005-11-01 at the Wayback Machine

- (in French) Patek et Czapek

- Patek Philippe Patents

- Facts about Patek Philippe Timepieces

- Patek Philippe: The Forgotten Beginnings

External links

[edit]- Watchmakers (people)

- Recipients of the Gold Cross of the Virtuti Militari

- 19th-century Polish businesspeople

- 19th-century Swiss businesspeople

- 19th-century Polish nobility

- Swiss nobility

- 1812 births

- 1877 deaths

- Immigrants to Switzerland

- Inventors

- November Uprising participants

- Activists of the Great Emigration

- Naturalised citizens of Switzerland

- Patek Philippe