Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi

| Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | A. ritzemabosi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi | |

Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi (Black currant nematode, Chrysanthemum foliar nematode, Chrysanthemum leaf nematode, Chrysanthemum nematode, Chrysanthemum Foliar eelworm) is a plant pathogenic nematode. It was first scientifically described in 1890 in England. This nematode has a wide host range. Among the most important species affected are Chrysanthemums and strawberries. A. ritzemabosi is a migratory foliar feeding nematode. It can feed both ectoparasitically and endoparasitically, with the later causing the most significant damage. When adequate moisture is present, this nematode enters the leaves and feeds from inside the tissue. Typical damage is characterized by necrotic zones between the veins of the leaves. Its lifecycle is short; only ten days from egg to mature adult. A single female can lay as many as 3,500 eggs. This pest can be difficult to control. Host plant resistance, hot water treatments, and predatory mites are recommended.

Nomenclature and Synonyms

First described in England in 1890, it was given the name Aphelenchus olesistus by Ritzema-Bos in 1893. In 1908, Markinowski grouped A. olesisyus, A. fragariae, and A. omerodis under the common name A. omerodis. A. olesistus was recognized as an individual species and given the current name Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi by Schwartz in 1911.[1] This species may also be known by the following synonyms: Aphelenchus ritzemabosi Schwartz 1911, Pathoaphelenchus ritzemabosi (Schwartz 1911), Steiner 1932, Aphelenchoides (Chitinoaphelenchus) ritzemabosi (Schwartz 1911) Fuchs 1937, Pseudaphelenchoides ritzemabosi (Schwartz 1911) Drozdovski 1967, Tylenchus ribes Taylor 1917, Aphelenchus ribes (Taylor 1917) Goodey 1932, Aphelenchoides ribes (Taylor 1917) Goodey 1933, Aphelenchus phyllophagus Stewart 1921[2]

Description

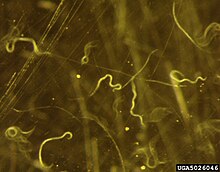

Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi ranges in length from 0.7 to 1.2 mm with the females of the species having the potential to be slightly longer than the males. Male A. ritzemabosi are often wider than females. The head is sharply differentiated from the body in that it is noticeably wider than the neck. This nematode has four lateral incisures. Females have at least two rows of oocytes and the spicule on the male nematodes is a short ventral process without outgrowths.[1]

Hosts and symptoms

A. ritezmabosi has a wide host range of almost 200 plant species, and is an important disease in chrysanthemum and other ornamentals.[3] Other ornamental hosts of A. ritzemabosi are anemones, asters, carnations, Chinaster, cinerarias, coneflowers, crassulas, creeping bellflower, dahlias, delphiniums, elders, lupines, monkeyflower, phlox, pouchflower, rhododendrons, sages, Siberian wallflower, water peperomia, and zinnias.[4] A common symptom of A. ritezmabosi is seen when the nematode is feeding in the foliar tissue. Angular lesions are formed, which are chlorotic at first then turn necrotic as the feeding persists.[3] A sign that an A. ritzeambosi nematode is feeding in the bud of a plant is brown scars on the bud and surrounding tissue. The nematode also produces secretions that have the ability to cause several other symptoms in infested plants including shortening of inter-nodes, creating a bushy appearance, browning and failure of the shoot to grow, as well as distorted leaf formation.[5]

Disease cycle

A. ritzemabosi is an endoparasitic nematode, meaning that it feeds on plant tissue from the inside of the cell.[6] Adult nematodes infest the leaves of their host plant by swimming up the outside of the stem in a film of water. This can only happen when the relative humidity is very high.[7] Once it has reached a leaf it enters through the stomata to begin feeding in an endoparasitic fashion.[3] Once inside the host it is capable of invading and infecting host tissue at all life stages, other than the egg. The more mature stages show an improved ability to migrate through host tissue.[3] When the growing season of the host comes to an end the nematode goes into a quiescent state overwintering inside the leaf tissue. When spring comes they end their quiescent state then find and infest a new host.[8]

A. ritzeambosi is also capable of feeding ectoparasitically, from the outside of the cell. It has been known to feed ectoparasitically on the buds of some plants such as strawberry and black currants. Above ground ectoparasitic feeding can only happen in events of prolonged high humidity or other circumstances providing a long term film of water on the plant which protects the nematode from exposure. Ectoparasitic feeding also happens on the roots in the soil.[6] All of this happens in an extremely short amount of time, it takes around 10 days for A. ritzembosi to go from egg to adult. All life stages are vermiform and migratory. [5]

Reproduction

Studies have shown that in optimal conditions a single female A. ritzemabosi can produce up to thousands of offspring in the period of about a month.[9] French & Barraclough (1961) obtained a maximum number of 3,500 progeny from a single A. ritzemabosi female after 38 days at mean greenhouse temperatures of 17° to 23 °C. Temperature influence on reproduction showed that higher temperatures generally lead to more reproductive actions. No reproduction was observed at temperatures of 8 degrees Celsius.[9] Fertilized females go on reproducing for six months without further fertilization [10] In chrysanthemum leaves, the female lays about 25-30 eggs in a compact group. These eggs hatch in 3–4 days and the juveniles take 9–10 days to reach maturity. The total life cycle takes 10–13 days [11] In susceptible varieties of Chrysanthemum, the female remains in one place within the leaf as it feeds on adjacent cells and continuously lays eggs. In resistant varieties, the female moves through the leaf laying only a few eggs as it goes. Few, if any of the juveniles make it to maturity.[11] Like many other plant parasitic nematodes, A. ritzemabosi has the ability to reproduce on fungal tissue, suggesting that soil fungus may contribute to the nematode's survival when no host is available.[12] Laboratory tests have shown that Botrytis cinerea and many Rhizoctonia species of fungi are more conducive to A. ritzeambosi growth and reproduction. These fungi are used to culture and propagate other Aphelenchid species as well.[13]

In adult females, the eggs can be seen developing inside their bodies before they are deposited to hatch. If an adult female is cut off from a reliable supply of food it has been observed that the egg will disappear from view, evidently being aborted and reabsorbed by the female.[9]

Environment

A.ritzeambosi has a very wide range. In the US, its distribution is restricted to California, Colorado, Florida, and Wyoming. It is widespread in Mexico. It is also present but restricted in Asia, including many provinces of China, Japan, Iran, and India. It is also present throughout Europe from Portugal to Siberia; it was once present in Denmark but has been eradicated. It is widespread in South Africa, and the Canary Islands.[14]

A. ritzemabosi is more commonly associated with temperate climates, even though it can be found in both tropical and temperate localities. It is best suited to thrive and reproduce when in highly humid environments, where it tends to be more active in infesting hosts than in dryer environments.[15] the optimal temperature for reproduction is 17 °C-23 °C.[16]

Management

Infected leaves and plants should be removed and destroyed. Since this nematode relies on moisture to move up the plant and between plants, care should be taken to avoid periods of wetness. Drip irrigation is preferable over overhead spray irrigation for this reason. This nematode is susceptible to elevated temperatures. A hot water treatment at a temperature of 115 degrees Fahrenheit for five minutes of dormant plant materials such as bulbs, runners or cuttings intended for propagation can be used and is effective at eliminating most nematodes that may be infesting the plant material.[17] Sanitation of equipment is also important to controlling the nematode. Pots potting soil, and tools should be cleaned by baking or steaming at 180-200 degrees Fahrenheit for 30 minuets.[18] Care must be taken so that the temperatures needed to eliminate the infesting nematodes does not irrevocably harm the plant material.[3] Parathion has proven to be a potent chemical control of A. ritzemabosi, especially in chrysanthemum.[3]

The Bulb Mite, Rhizoglyphus echinopus, is a known predator of A. ritzemabosi and can serve in biological control practices.[19]

Host-plant resistance is also used to control A. ritzemabosi. The following cultivars of Chrysanthemum are resistant to this pest: Amy Shoesmith, Delightful, Orange Beauty, and Orange Peach Blossom. These are listed as resistant but not immune. This implies that the plant may still be attacked by adult nematodes but reproduction is highly reduced if not prevented.[20]

Importance

Infection of various plants by A. ritzemabosi is likely to cause some degree of yield loss to growers where the nematode is present since photosynthetic area of the leaves is damaged or destroyed as the nematodes feed and reproduce.[21] However, this nematode is not considered to cause economic loss unless environmental conditions are very suitable.

In 1981, Crop losses from plant-parasitic nematodes in the USA were estimated by the United State Department of Agriculture (USDA) at about $4.0 billion per year.[22]

A. ritzeambosi causes substantial economic loss in basil crops in Italy as it infects the economically valuable portion of the plant.[23]

A. ritzemabosi is a serious pest of strawberry in Ireland, where yield reductions up to 60% have been recorded. The crown weight of strawberry cv. Senga Sengana was reduced by 51% by A. ritzemabosi. This damage results in fruit yield loss of up to 65%. A. ritzemabosi infections can reduce the number of runners by up to 25-30%. The level of susceptibility varies among cultivars. An infection by A. ritzemabosi can cause average yield losses of an estimated 53.4% in the strawberry variety Korallovaya 100. The variety Yasna seems to be somewhat less susceptible to A. ritzemabosi than Korallovaya 100 or Muto. In Poland, A. ritzemabosi infestation destroyed 45% of chrysanthemum plants on a holding, and for the most susceptible varieties the number was as high as 92%.[24]

This organism is a 'C' rated pest in the U.S. state of California, meaning that it is not subject to state enforcement outside of nurseries except to retard spread or to provide for pest cleanliness in nurseries. For a sense of how that relates to other plant pests, an 'A' rated pest is an organism of known economic importance subject to action enforced by the state (or County Agricultural Commissioner acting as a state agent) involving: eradication, quarantine regulation, containment, rejection, or other holding action such as Aphelenchoides besseyi (strawberry summer dwarf nematode).[25]

References

- ^ a b Decker, Heinz. Plant Nematodes and their Control. Phytonematology. 1981. Amerind Publishing Co. New Delhi.

- ^ Ferris, Howard. "Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi". UCDavis. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Jenkins, W. R. & Taylor D. P. (1967) Plant Nematology. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corp.

- ^ University of Illinois Extension. Report on Plant Disease. RPD No.1102 July 2000.

- ^ Plant Pathology, Gorge N. Agrios. Academic Press, 2005. p868 & 869

- ^ a b Maggenti, Armand (1981). General Nematology. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90588-X.

- ^ Siddiqi, M. R. 1974: Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi. CIH descriptions of plant-parasitic nematodes. Set 3, No. 32.

- ^ Hesling, J. J.; Wallace, H. R. 1961: Observations on the biology of chrysanthemum eelworm Aphelenchoides ritzema-bosi (Schwartz) Steiner in florists' chrysanthemum.1. Spread of eelworm infestation. Annals of applied biology 49: 195 - 203.

- ^ a b c J. S. DOLLIVER 1), A. C. HILDEBRANDT, & A. J. RIKERSTUDIES OF REPRODUCTION OF APHELENCHOIDES RITZEMABOSI (SCHWARTZ) ON PLANT TISSUES IN CULTURE. Department of Plant Pathology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, U.S.A. 2)

- ^ French N, Barraclough R, 1961. Observations on the reproduction of Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi (Schwartz). Nematologica, 6:89-94.

- ^ a b Wallace HR, 1960. Observations on the behaviour of Aphelenchoides ritzema-bosi in chrysanthemum leaves. Nematologica, 5:315-321.

- ^ Hooper DJ, Cowland JA, 1986. Fungal hosts for the chrysanthemum nematode, Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi. Plant Pathology, 35:128-129.

- ^ Hooper D, Cowland J. Fungal hosts for the chrysanthemum nematode, Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi. Plant Pathology [serial online]. March 1986;35(1):128-129. Available from: Academic Search Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 5, 2012.

- ^ Invasive Species Compendium www.cabi.org

- ^ Kohl, L. M. 2011. Astronauts of the Nematode World: An Aerial View of Foliar Nematode Biology, Epidemiology, and Host Range. APSnet Features. doi:10.1094/APSnetFeature-2011-0111.

- ^ Identifying Landscapes for Greater Prairie Chicken Translocation Using Habitat Models and GIS: A Case Study Neal D. Niemuth Wildlife Society Bulletin , Vol. 31, No. 1 (Spring, 2003), pp. 145-155 Published by: Allen Press Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3784368

- ^ Observations on the biology of chrysanthemum eelworm Aphelenchoides ritzema- bosi (Schwartz) Steiner in florists’ chrysanthemum I. Spread of eelworm infestation

- ^ University of Illinois Extension Report on Plant Disease. RPD No. 1102, July 2000.

- ^ Sturhan D, Hampel G, 1977. Plant-parasitic nematodes as prey of the bulb mite Rhizoglyphus echinopus (Acarina, Tyroglyphidae). Anzieger für Schadlingskunde, Pflanzenschutz, Umweltschutz, 50:115-118

- ^ Ferris, Howard. "Host Plant Resistance to a Genus and species of Plant-feeding Nematodes". UCDavis. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Franc, Gary; Colette Beaupre (1993). "A Mew Disease of Pinto Bean caused by Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi and its Associated Foliar Symptoms".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Pimentel, D. (1981). Handbook of Pest Management in Agriculture. 1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ^ Nicola Vovlas et al. 2005. Identification and histopathology of the foliar nematode Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi (Nematoda:Aphelenchoididae)

- ^ http://www.plantwise.org Chrysanthemum foliar eelworm ( Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi ). http://www.plantwise.org/?dsid=6384&loadmodule=plantwisedatasheet&page=4270&site=234

- ^ Importance: "Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi". Retrieved 25 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- Aphelenchoides ritzemabosi information at University of California, Davis