Arrhenius equation

The Arrhenius equation is a formula for the temperature dependence of reaction rates. The equation was proposed by Svante Arrhenius in 1889, based on the work of Dutch chemist Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff who had noted in 1884 that Van 't Hoff's equation for the temperature dependence of equilibrium constants suggests such a formula for the rates of both forward and reverse reactions. Arrhenius provided a physical justification and interpretation for the formula.[1][2][3] Currently, it is best seen as an empirical relationship.[4] It can be used to model the temperature variation of diffusion coefficients, population of crystal vacancies, creep rates, and many other thermally-induced processes/reactions. The Eyring equation, developed in 1935, also expresses the relationship between rate and energy.

A historically useful generalization supported by Arrhenius' equation is that, for many common chemical reactions at room temperature, the reaction rate doubles for every 10 degree Celsius increase in temperature.[5]

Equation

Arrhenius' equation gives the dependence of the rate constant of a chemical reaction on the absolute temperature (in kelvins), where is the pre-exponential factor (or simply the prefactor), is the activation energy, and is the universal gas constant:[1][2][3]

Alternatively, the equation may be expressed as

The only difference is the energy units of : the former form uses energy per mole, which is common in chemistry, while the latter form uses energy per molecule directly, which is common in physics. The different units are accounted for in using either = gas constant or the Boltzmann constant as the multiplier of temperature .

The units of the pre-exponential factor are identical to those of the rate constant and will vary depending on the order of the reaction. If the reaction is first order it has the units s−1, and for that reason it is often called the frequency factor or attempt frequency of the reaction. Most simply, is the number of collisions that result in a reaction per second, is the total number of collisions (leading to a reaction or not) per second and is the probability that any given collision will result in a reaction. It can be seen that either increasing the temperature or decreasing the activation energy (for example through the use of catalysts) will result in an increase in rate of reaction.

Given the small temperature range kinetic studies occur in, it is reasonable to approximate the activation energy as being independent of the temperature. Similarly, under a wide range of practical conditions, the weak temperature dependence of the pre-exponential factor is negligible compared to the temperature dependence of the factor; except in the case of "barrierless" diffusion-limited reactions, in which case the pre-exponential factor is dominant and is directly observable.

Arrhenius plot

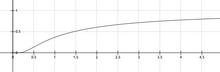

Taking the natural logarithm of Arrhenius' equation yields:

Rearranging yields:

This has the same form as an equation for a straight line:

- ,

where x is the reciprocal of T.

So, when a reaction has a rate constant that obeys Arrhenius' equation, a plot of ln(k) versus T −1 gives a straight line, whose gradient and intercept can be used to determine Ea and A . This procedure has become so common in experimental chemical kinetics that practitioners have taken to using it to define the activation energy for a reaction. That is the activation energy is defined to be (-R) times the slope of a plot of ln(k) vs. (1/T )

Modified Arrhenius' equation

The modified Arrhenius' equation[6] makes explicit the temperature dependence of the pre-exponential factor. The modified equation is usually of the form

where T0 is a reference temperature and allows n to be a unitless power. Clearly the original Arrhenius expression above corresponds to n = 0. Fitted rate constants typically lie in the range -1<n<1. Theoretical analyses yield various predictions for n. It has been pointed out that "it is not feasible to establish, on the basis of temperature studies of the rate constant, whether the predicted T½ dependence of the pre-exponential factor is observed experimentally."[4] However, if additional evidence is available, from theory and/or from experiment (such as density dependence), there is no obstacle to incisive tests of the Arrhenius law.

Another common modification is the stretched exponential form: [citation needed]

where β is a dimensionless number of order 1. This is typically regarded as a purely empirical correction or fudge factor to make the model fit the data, but can have theoretical meaning, for example showing the presence of a range of activation energies or in special cases like the Mott variable range hopping.

Theoretical interpretation of the equation

Arrhenius' Concept of Activation Energy

Arrhenius argued that for reactants to transform into products, they must first acquire a minimum amount of energy, called the activation energy Ea. At an absolute temperature T, the fraction of molecules that have a kinetic energy greater than Ea can be calculated from statistical mechanics. The concept of activation energy explains the exponential nature of the relationship, and in one way or another, it is present in all kinetic theories.

The calculations for reaction rate constants involve an energy averaging over a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution with as lower bound and so are often of the type of incomplete gamma functions, which turn out to be proportional to .

Collision theory

One example comes from the "collision theory" of chemical reactions, developed by Max Trautz and William Lewis in the years 1916-18. In this theory, molecules are supposed to react if they collide with a relative kinetic energy along their lines-of-center that exceeds Ea. This leads to an expression very similar to the Arrhenius equation.

Transition state theory

Another Arrhenius-like expression appears in the "transition state theory" of chemical reactions, formulated by Wigner, Eyring, Polanyi and Evans in the 1930s. This takes various forms, but one of the most common is

where is the Gibbs energy of activation, is Boltzmann's constant, and is Planck's constant.

At first sight this looks like an exponential multiplied by a factor that is linear in temperature. However, one must remember that free energy is itself a temperature dependent quantity. The free energy of activation is the difference of an enthalpy term and an entropy term multiplied by the absolute temperature. When all of the details are worked out one ends up with an expression that again takes the form of an Arrhenius exponential multiplied by a slowly varying function of T. The precise form of the temperature dependence depends upon the reaction, and can be calculated using formulas from statistical mechanics involving the partition functions of the reactants and of the activated complex.

Limitations of the idea of Arrhenius activation energy

Both the Arrhenius activation energy and the rate constant k are experimentally determined, and represent macroscopic reaction-specific parameters that are not simply related to threshold energies and the success of individual collisions at the molecular level. Consider a particular collision (an elementary reaction) between molecules A and B. The collision angle, the relative translational energy, the internal (particularly vibrational) energy will all determine the chance that the collision will produce a product molecule AB. Macroscopic measurements of E and k are the result of many individual collisions with differing collision parameters. To probe reaction rates at molecular level, experiments are conducted under near-collisional conditions and this subject is often called molecular reaction dynamics.[7]

There are deviations from the Arrhenius law during the glass transition in all classes of glass-forming matter.[8] The Arrhenius law predicts that the motion of the structural units (atoms, molecules, ions, etc.) should slow down at a slower rate through the glass transition than is experimentally observed. In other words the structural units slow down at a faster rate than is predicted by the Arrhenius law. This observation is made reasonable assuming that the units must overcome an energy barrier by means of a thermal activation energy. The thermal energy must be high enough to allow for translational motion of the units which leads to viscous flow of the material.

See also

- Accelerated aging

- Eyring equation

- Q10 (temperature coefficient)

- Van 't Hoff equation

- Clausius–Clapeyron relation

- Gibbs–Helmholtz equation

- Cherry blossom front - predicted using the Arrhenius equation

References

- ^ a b Arrhenius, S.A. (1889). "Über die Dissociationswärme und den Einflusß der Temperatur auf den Dissociationsgrad der Elektrolyte". Z. Physik. Chem. 4: 96–116.

- ^ a b Arrhenius, S.A. (1889). "Über die Reaktionsgeschwindigkeit bei der Inversion von Rohrzucker durch Säuren". ibid. 4: 226–248.

- ^ a b Laidler, K. J. (1987) Chemical Kinetics,Third Edition, Harper & Row, p.42

- ^ a b Kenneth Connors, Chemical Kinetics, 1990, VCH Publishers

- ^ Pauling, L.C. (1988) General Chemistry, Dover Publications

- ^ IUPAC Goldbook definition of modified Arrhenius equation

- ^ Levine, R.D. (2005) Molecular Reaction Dynamics, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Bauer, Th.; Lunkenheimer, P.; Loidl, A. (2013). "Cooperativity and the Freezing of Molecular Motion at the Glass Transition". Physical Review Letters. 111 (22): 225702. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.225702.

Bibliography

- Pauling, L.C. (1988) "General Chemistry", Dover Publications

- Laidler, K. J. (1987) Chemical Kinetics, Third Edition, Harper & Row

- Laidler, K. J. (1993) The World of Physical Chemistry, Oxford University Press

External links

- Carbon Dioxide solubility in Polyethylene - Using Arrhenius equation for calculating species solubility in polymers

![{\displaystyle \ E_{a}\equiv -R\left[{\frac {\partial \ln k}{\partial ~(1/T)}}\right]_{P}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ced30491950c8daf11f19edfb3b96a997db9fe2d)

![{\displaystyle k=A\exp \left[-\left({\frac {E_{a}}{RT}}\right)^{\beta }\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3f2736359746a38bb3416c9e56a64e256343d656)