Battle of Camas Creek

| Battle of Camas Creek | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nez Perce War | |||||||

Camas Meadows, 2003 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| United States Army | Nez Perce | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

General Oliver Howard Capt. Randolph Norwood |

Chief Joseph Looking Glass White Bird Ollokot Toohoolhoolzote | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 300 men | <200 warriors [1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3 killed 6 wounded[2] | Probably only 2 wounded[3] | ||||||

Location in the United States Location in Idaho Territory | |||||||

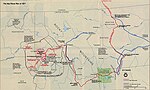

The Battle of Camas Creek, August 20, 1877, was a raid by the Nez Perce people on a United States Army encampment in Idaho Territory and a subsequent battle during the Nez Perce War. The Nez Perce defeated three companies of U.S. cavalry and continued their fighting retreat to escape the army.

Background

[edit]After sustaining heavy casualties at the Battle of the Big Hole on August 9–10, the Nez Perce proceeded southward though Montana Territory, crossed into Idaho Territory again at Bannock Pass, and descended into the valley of the Lemhi River. The Nez Perce were aware that the U.S. Army was in pursuit; to confound them, they took a circuitous route less familiar than their usual direct route to the Montana Great Plains. During this section of their retreat, their guide and the leader of their march was a half-Nez Perce, half-French man of several names, the most common being Poker Joe.[4] The White settlers in the Lemhi Valley had been warned that the Nez Perce might be coming their way and most of them had fled to the town of Lemhi.

The pursuer of the Nez Perce, Brigadier General Oliver O. Howard, did not follow them directly, but rather took a shorter route to the east across southern Montana to intercept them near Yellowstone National Park. Howard had 310 soldiers plus a varying number of civilian volunteers, usually several dozen, and Indian scouts, primarily Bannocks, but also some Nez Perce friendly to the U.S. Howard detached 50 men, including Indian scouts, under Lt. George R. Bacon to rush ahead and guard Red Rock Pass, thus hoping to catch the Nez Perce between his and Bacon's soldiers.[5][6] Howard was coming under severe criticism for his failure to defeat the Nez Perce during a campaign that had now lasted two months.[7]

The Nez Perce pursued by Howard probably numbered, after their losses at the Big Hole battle, about 700 persons with fewer than 200 warriors.

Birch Creek

[edit]The death of many Nez Perce women and children at the Big Hole Battle caused a thirst for revenge among the young warriors of the Nez Perce and their leaders were not able to restrain them.[8]

On August 12, the Nez Perce killed five ranchers on Horse Prairie, Montana. On August 13, after crossing into Idaho over Bannock Pass, the Nez Perce encountered a stockade full of White settlers at Junction. Leaders Looking Glass and White Bird met with the settlers and expressed their friendship for the settlers.[9]

Two days later, the Nez Perce on Birch Creek encountered a caravan of eight covered wagons and eight men. The initial contact was friendly, but after the Indians demanded and were served whiskey the situation became ugly and five of the Whites were killed. One White escaped and two Chinese were released. One Nez Perce was killed, apparently in a drunken brawl with another warrior. The leaders poured the remainder of the whiskey on the ground and burned the wagons.[8][10]

Race to Camas Meadows

[edit]From Birch Creek the Nez Perce turned eastward and headed toward Henrys Lake. Howard's route paralleled them to the north in Montana on the other side of the continental divide. Howard's plan was to cross into Idaho at Monida Pass (present-day Interstate 15) and intercept the Nez Perce at Camas Creek near Dubois. On August 17, Howard was overtaken by 39 Virginia City volunteers under the command of James E. Callaway, who joined Howard's cavalry.[11][12]

That same day, Captain Randolph Norwood and fifty fresh cavalry men, designated as Company 4 of the Second Infantry, also overtook Howard's command. Howard expended all energy to intercept the Nez Perce near Camas Creek. He was a day late. Bannock Indian scouts, ahead of Howard's cavalry, observed the Nez Perce rear guard cross the road toward Camas Meadows. Chief Buffalo Horn, one of Howard's scouts, obtained a view of their camp.

On August 18, the Nez Perce camped at Camas Meadows fifteen miles (24 km) to Howard's east in a meadow bisected by Spring and Camas creeks. The Nez Perce name for their camp was Kamisnim Takin, meaning "camas meadows".[13] Howard marched to Camas Meadows on August 19. The Nez Perce had departed earlier that day, continuing eastward. Howard set up camp there that night, calling it Camp Callaway, and took "great pains" to "cover the camp with pickets in every direction."[14]

The Raid

[edit]

The exceptional precautions Howard had taken for the protection of Camp Callaway were observed by Nez Perce scouts. Upon returning to their own camp, they reported what they had seen to the chiefs. They decided to carry out a raid with the objective of putting Howard's cavalry on foot. The numbers of the raiders is disputed, although it was at least 28 and possibly many more.[15] The chiefs did not envision a battle. Yellow Wolf described the movements of the band:

We traveled slowly. No talking loud, no smoking. The match must not be seen. We went a good distance and then divided into two parties - one on each side of the creek... Before reaching the soldier camp, all stopped, and the leaders held council. How make the attack? The older men did this planning. Some wanted to leave the horses and enter the camp on foot. Chief Looking Glass and others thought the horses must not be left out. This last plan was chosen - to go mounted. Chief Joseph was not along.[16]

About 4:00 a.m., several Nez Perce dismounted and crept among the picketed horses to cut them loose. Then two things happened simultaneously. As the mounted column approached the soldier's camp, a sentry shouted, "Who goes there?" At the same moment, a foot scout named Otskai accidentally discharged his gun in the midst of the camp.[13] Thus, an alarm was sounded from two places before many horses had been released from their picket lines. However, two hundred mules were free and the Indians concentrated upon stampeding them northward. This enabled the raiders to control the loose stock. In spite of all the shouting, several men thought they heard "the great voice of Looking Glass" booming out orders.[17] Bullets were flying about and some of them struck the wagons, but only one soldier was hit, and his wound was slight. Darkness, noise, and surprise compounded the confusion, but the cavalry officers and men quickly dressed and mounted.

General Howard ordered a strong force organized in order to pursue the raiders and recover the stock. Within minutes, three companies of cavalry were assembled. By dawn, nearly 150 horsemen were galloping northward in pursuit of the raiders, who had several miles' head start. In addition to the mules, about 20 horses belonging to the Virginia City volunteers were missing. It was reported that the volunteers received $150 per head from the government in compensation for their lost mounts.[18][19]

A newspaper reporter described the raid:

Oh, I am one of the volunteers, who marched right home on the tramp, tramp, When Joseph set the boys afoot, at the battle of Callaway's camp.[20]

The Battle of Camas Meadows

[edit]Under the command of Major Sanford, the cavalry companies of Captains Carr, Jackson, and Norwood, numbering about 150 men, set off at dawn in pursuit of the Nez Perce and the stolen mules. The rear guard of the Nez Perce detected them and set up an ambush eight miles (13 km) north of Camp Callaway. Several warriors continued driving the mules on to camp, and others deployed among hillocks of black lava and broken terrain dotted with Aspen trees and sagebrush. A few Nez Perce deployed in a thin skirmish line in a grassy meadow about a half-mile (0.8 km) wide. The meadow was bordered on the opposite side by a lava ridge 18 feet (5.5 m) high and 500 to 600 feet (150 to 180 m) long. Sanford and his three companies took up positions behind the ridge and dismounted to return long-distance fire from the Nez Perce.[21][22]

The distance between these lines was too great for effective marksmanship, but when a shot struck Lt. Benson in the hip the soldiers discovered that the Indians in the meadow were serving as a decoy, while others had been creeping forward on both flanks to enfilade the troops. Hence, Sanford ordered a bugler to call a retreat. The retreat of the cavalrymen whose horses had been taken to the rear was an occasion of excitement and confusion. Captain Randolph Norwood with fifty men, however, declined to obey immediately the order to retreat, but instead backtracked slowly to a strong position where he was forced by the encircling Nez Perce to halt, establish defensive positions, and fight it out. The other two companies had abandoned him, and for the next two to four hours, the two sides sniped at each other.

Meanwhile, Howard received word via messenger that the cavalry companies were in trouble and sallied forth from Camp Callaway with reinforcements. He found the two retreating cavalry companies. Captain Sandford professed ignorance as to the location and fate of Captain Norwood. Howard pushed forward and, mid-afternoon, came upon Norwood and his men crouching in their lava rock rifle pits located a few rods apart along the top and on the edges of a series of ridges that enclosed a protected area for their horses. The Indians melted away and the battle was over.

Norwood had one man dead, two mortally wounded and six to nine wounded.[22][23] Yellow Wolf stated that "no Indian was badly hurt, only one or two just grazed by bullets". Wottolen was wounded in the side, and Tholekt's head was creased.[22]

Aftermath

[edit]The Nez Perce were disappointed that the spoils of their raid had been mostly mules, but the loss crippled Howard's mobility. Howard had failed to defeat the Nez Perce on several occasions and now, after the battle, he failed to pursue them aggressively. A journalist thought that was for the best. "I candidly think Joseph could whip our cavalry and cannot blame General Howard for not giving him battle."[24]

On the evening after the battle, Howard was reinforced by 280 infantry under Captain Marcus Miller. Two days later on August 22, fifty Bannocks, under the leadership of Buffalo Horn, rode into the camp. They were a "gorgeous set of warriors, hair dyed...decorated with...sleigh bells and feathers" and wearing buckskin and brightly colored blankets. They had been promised all the Nez Perce horses they could capture."[25] An unusually talented White scout, Stanton G. Fisher, and the Bannocks explored ahead. Howard followed slowly, so slowly that Buffalo Head and many of the Bannocks quit the army in disgust and went home and Fisher commented, "Uncle Sam's boys are too slow for this business."[26]

After learning that the Nez Perce had crossed into the wilderness of Yellowstone National Park, Howard called a halt to the chase and rested for several days at Henrys Lake. Howard's troops were tired, having marched for 26 days averaging twenty miles (32 km) a day. The Nez Perce, burdened with wounded, women, children, and elderly had gone faster and further but, in the words of a journalist, they had the "faculty of stealing fresh horses from the settlers."[27]

Meanwhile, Howard's superior General Philip Sheridan was collecting more than one thousand experienced soldiers and Indian scouts from many tribes to defeat the Nez Perce when they emerged from Yellowstone.[28]

Legacy

[edit]The sites of Howard's encampment, where the incident began, and the later siege, were designated a National Historic Landmark as the Camas Meadows Battle Sites in 1989, are part of the Nez Perce National Historical Park and the Nez Perce National Historic Trail. The sites are undeveloped, except for a grave marker at the site of the encampment. Rifle pits dug by Captain Norwood's men survive at the siege location.

References

[edit]- ^ "The August 20, 1877 Battle of Camas Creek". Anishinabe History. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ Beal, Merrill D. (1963). "I Will Fight no More Forever." Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce War. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. pp. 156, 159–160.

- ^ Beal, p. 159

- ^ Josephy, Jr., Alvin M. (1965). The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 575, 590.

- ^ Brown, Mark H. (1967). The Flight of the Nez Perce. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 268.

- ^ Beal, p. 146

- ^ Josephy, p. 598

- ^ a b Josephy, p. 593

- ^ Greene, Jerome A. (2000). Nez Perce Summer 1877: The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0917298683.

- ^ Brown, p. 284

- ^ Brown, p. 289

- ^ Hampton, Bruce (1994). Children of Grace: The Nez Perce War of 1877. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9780805019919.

- ^ a b Beal, pp. 565-560

- ^ Brown, p. 290

- ^ Hampton, p. 208

- ^ McWorter, Lucullus Virgil (1940). "Yellow Wolf: His Own Story". Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, Ltd.

- ^ Dillon Examiner, September 3, 1941

- ^ Helena Daily Independent, June 15, 1896

- ^ Hampton p. 209

- ^ Beal, p. 157

- ^ Brown, p. 293-295

- ^ a b c Norwood, Randolph. "Report to Colonel John Gibbon, written on Upper Madison River, August 24, 1877." Document No. 3754 DD 1877, National Archives.

- ^ Brown, pp. 292-297

- ^ Hampton, p. 213

- ^ Hampton, pp. 214, 217

- ^ Hampton, pp. 216, 243

- ^ Hampton, p. 217

- ^ Hampton, p. 221