Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung

| |

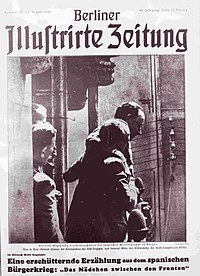

Cover of issue of 26 August 1936: first meeting between Francisco Franco and Emilio Mola | |

| Frequency | weekly |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1891 |

| First issue | 4 January 1892 |

| Final issue | 1945 |

| Company | Ullstein Verlag |

| Country | Germany |

| Based in | Berlin |

| Language | German |

The Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, often abbreviated BIZ, was a German weekly illustrated magazine published in Berlin from 1892 to 1945. It was the first mass-market German magazine and pioneered the format of the illustrated news magazine.

The Berliner Illustrirte was published on Thursdays but bore the date of the following Sunday.[1]

History

[edit]The magazine was founded in November 1891[2] by a Silesian businessman named Hepner[3][4] and published its first issue on 4 January 1892 under Otto Eysler, who also published Lustige Blätter. In 1894, Leopold Ullstein, the founder of the publishing house Ullstein Verlag, bought it.[5] In 1897 it cost RM 1.50 per quarter; by comparison the Illustrirte Zeitung of Leipzig, which had been founded in 1843, had approximately twice as many pages and cost RM 7 per year, prohibitively expensive for all but the well to do.[6] Technical advances including photo-offset printing, the linotype machine and cheaper production of paper later made it possible to sell it for 10 pfennigs an issue, which was within the reach even of workers. At the suggestion of the business manager, David Cohn, Ullstein lifted the subscription requirement, and it was then sold in the street (which had been illegal until 1904), at station kiosks and in drinking establishments as well as by a force of female subscription sellers, and became the first mass-market periodical in Germany.[4][6][7] (The price doubled to 20 pfennigs in November 1923 when the currency was stabilised after the runaway inflation of the early 1920s.[8])

Once it no longer required a subscription, the Berliner Illustrirte fundamentally changed the newspaper market, attracting readers by its appearance, particularly the eye-catching pictures. The first cover created a sensation, featuring a group portrait of officers who had been killed in a shipwreck. Initially it was illustrated with engravings, but it soon embraced photographs. Beginning in 1901, it was also technically feasible to print photographs inside the magazine, a revolutionary innovation. Building on the example of a rival Berlin publication, August Scherl's Die Woche, Ullstein developed it into the prototype of the modern news magazine.[5] It pioneered the photo-essay,[5][9] had a specialised staff and production unit for pictures and maintained a photo library.[4] With other news magazines like the Münchner Illustrierte Presse in Munich and Vu in France, it also pioneered the use of candid photographs taken with the new smaller cameras.[10] In August 1919, a cover photograph of the German President Friedrich Ebert and Minister of Defence Gustav Noske on holiday on the Baltic coast, clad in swimming trunks, caused heated debate about propriety; within a decade, such informality would seem normal.[11] Kurt Korff (Kurt Karfunkelstein), then the editor in chief, pointed out in 1927 the parallel with the rise of the cinema, another aspect of the increasing role of "life 'through the eyes'".[12] He and publishing director Kurt Szafranski sought out reporters who could tell a story using photographs, notably the pioneer sports photographer Martin Munkácsi, the first staff photographer at a German illustrated magazine,[13][14] and Erich Salomon, one of the founders of photo-journalism.[15] After initially working in advertising for Ullstein, Salomon signed an exclusive contract with the Berliner Illustrirte as a photographer and contributed both inside shots of meetings of world leaders[10][16][17] and photo-essays on the strangeness of life in the US, for example eating at automats (for which he used staged photographs depicting himself being schooled in how it was done).[18]

The magazine also strove for the most up-to-the-minute coverage possible, beginning in 1895 when a photograph from a fire was submitted; the engineer who had taken it was encouraged to provide more news photographs and a few weeks later founded the photography firm of Zander & Labisch.[19] In April 1912, the presses were stopped when the news came in of the sinking of RMS Titanic, and a half-page photo of the Acropolis was replaced with one of the ship.

The Berliner Illustrirte also featured drawings. The cover image of the 23 April 1912 issue was an allegorical drawing of the iceberg which claimed the Titanic as death,[20][21] and the strip cartoon Vater und Sohn by E. O. Plauen (Erich Ohser) was the most popular in 1930s Germany.[22] In the 1910s, the magazine awarded a prize for the year's best drawing, the Menzelpreis, presumably named for Berlin artist Adolph Menzel. Winners included Fritz Koch and Heinrich Zille.[23][24]

In 1928, when it was the largest weekly in Europe by circulation, the magazine published Vicki Baum's novel of the New Woman, Stud. chem. Helene Willfüer, in serial form. It provoked heated discussions and required repeated increases in the print runs until they exceeded 2 million.[25]

Appeal to the common reader also included competitions; for example, in May–June 1928, a contest called Büb oder Mädel offered prizes to readers who could correctly identify the sex of young people in six photographs.[26]

The magazine was publishing a million copies by 1914[4] and 1.8 million by the end of the 1920s;[27] in 1929, it was the only German magazine to approach the circulation numbers of the large American weeklies.[28] In 1931, its circulation was almost 2 million: 1,950,000.[29] Meanwhile, that of the rival Die Woche had fallen from 400,000 in 1900 to 200,000 in 1929.[30] From 1926 to 1931, news periodicals in Germany had their own aircraft deliver copies to remote places; Luft Hansa then took over this function.

Under the Third Reich, the Berliner Illustrirte like all other German publications was subject to Joseph Goebbels' Propaganda Ministry. In the 25 March 1934 issue it began serial publication of Hermann Göring's memoirs, written by Eberhard Koebsell, but was forced to withdraw them after Goebbels objected.[31] In mid-1934 the Ullstein family business was "aryanised",[32] and the Berliner Illustrirte became an organ of Nazi propaganda; previously non-political, with the outbreak of war in 1939, it started featuring stories about the military and German victories.[33] One of its noted photojournalists, Eric Borchert, was embedded with Erwin Rommel's troops in early 1941 to produce propaganda photos of the Africa campaign, along with a cinematographer and an artist.[34] Also in 1941, the old-fashioned spelling of its name (sometimes described as a mistake),[35] which had been retained when the masthead was modernised at the turn of the century,[36] was finally changed to the more modern Illustrierte.[37][38] By 1944 it was the only survivor of the twelve independent illustrated news magazines that had existed in Germany in 1939—five others continued to publish in name only, with the same contents as the Berliner Illustrierte—[39] and with the fall of Nazi Germany in 1945, regular production ceased: on April 22 the last copies were printed, and an SS detachment occupied the printing plant "to protect" it from the invading Soviets.[40][41]

After the war, the Ullstein family regained control of the publishing company but beginning in 1956, gradually sold it to Axel Springer. Axel Springer AG published special editions of the magazine, the first a 1961 issue sent free to powerful Americans that picked up the page numbering where the last wartime edition had left off and marked U.S. President John F. Kennedy's visit to Berlin;[42] another marked the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989; for these it returned to the original spelling of the name. Since 18 March 1984, the Sunday supplement to the company's Berliner Morgenpost newspaper has borne the name.

References

[edit]- ^ Peter de Mendelssohn, Zeitungsstadt Berlin: Menschen und Mächte in der Geschichte der deutschen Presse, Berlin: Ullstein, 1959, OCLC 3006301, p. 364 (2nd ed. Frankfurt/Berlin/Vienna: Ullstein, 1982, ISBN 9783550074967) (in German)

- ^ Gideon Reuveni (2006). Reading Germany: Literature and Consumer Culture in Germany Before 1933. Berghahn Books. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-84545-087-8. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d Corey Ross, Media and the Making of Modern Germany: Mass Communications, Society, and Politics from the Empire to the Third Reich, Oxford/New York: Oxford University, 2008, ISBN 9780191557293, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Mila Ganeva, Women in Weimar Fashion: Discourses and Displays in German Culture, 1918–1933, Screen cultures, Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2008, ISBN 9781571132055, p. 53.

- ^ a b Werner Faulstich, Medienwandel im Industrie- und Massenzeitalter (1830–1900), Geschichte der Medien 5, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2004, ISBN 9783525207918, p. 73 (in German)

- ^ de Mendelssohn, pp. 104–08.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 256.

- ^ Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2002, ISBN 9780810905597, p. 235.

- ^ a b Brett Abbott, Engaged Observers: Documentary Photography Since the Sixties, Exhibition catalogue, Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010, ISBN 9781606060223, p. 6.

- ^ Gail Finney, Visual Culture in Twentieth-Century Germany: Text as Spectacle, Bloomington: Indiana University, 2006, ISBN 9780253347183, p. 225.

- ^ Kurt Korff, "Die 'Berliner Illustrirte'", in: Fünfzig Jahre Ullstein, 1877–1927, ed. Max Osborn, Berlin: Ullstein, 1927, OCLC 919765, pp. 297–302, p. 290, cited in Ganeva, p. 53, p. 78, note 13, Ross, p. 34 and note 61, and de Mendelssohn, p. 112.

- ^ Tim Gidal, "Modern Photojournalism: The First Years", Creative Camera, July/August 1982, repr. in: David Brittain, ed., Creative Camera: 30 Years of Writing, Critical Image, Manchester: Manchester University, 1999, ISBN 9780719058042, pp. 73–80, p. 75.

- ^ Maria Morris Hambourg, "Photography between the Wars: Selections from the Ford Motor Company Collection", The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin N.S. 45.4, Spring 1988, pp. 5–56, p. 17.

- ^ Sherre Lynn Paris, "Raising Press Photography to Visual Communication in American Schools of Journalism, with Attention to the Universities of Missouri and Texas, 1880s–1990s", Dissertation, University of Texas, 2007, OCLC 311853822, p. 116[permanent dead link].

- ^ Marien, p. 237.

- ^ Daniel H. Magilow, The Photography of Crisis: The Photo Essays of Weimar Germany, University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 2012, ISBN 9780271054223, p. 124.

- ^ "Essen am laufenden Band", 1930; Rob Kroes, Photographic Memories: Private Pictures, Public Images, and American History, Interfaces, studies in visual culture, Hanover, New Hampshire: Dartmouth College/University Press of New England, 2007, ISBN 9781584655961, pp. 64–65.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 109.

- ^ Titanic: ein Medienmythos, ed. Werner Köster and Thomas Lischeid, Reclam-Bibliothek 1712, Leipzig: Reclam, 2000, ISBN 9783379017121, p. 28 (in German)

- ^ "Die erste Nachricht über den Untergang der 'Titanic'", Medienpraxis blog, 15 April 2012 (in German), with image.

- ^ René Mounajed, Geschichte in Sequenzen: Über den Einsatz von Geschichtscomics im Geschichtsunterricht, Dissertation University of Göttingen, 1988, Frankfurt: Lang, 2009, ISBN 9783631591666, pp. 27–28 and note 72 (in German)

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 111.

- ^ Die Kunst für Alle 26 (1911) p. 86 (in German)

- ^ Kerstin Barndt, Sentiment und Sachlichkeit: Der Roman der Neuen Frau in der Weimarer Republik, Literatur, Kultur, Geschlecht 19, Cologne: Böhlau, 2003, ISBN 9783412097011, p. 65 (in German). The novel was published in English translation as Helene.

- ^ Maud Lavin, "Androgyny, Spectatorship, and the Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Höch", New German Critique 51, Autumn 1990, pp. 62–86, p. 75.

- ^ István Deák, Weimar Germany's Left-wing Intellectuals: A Political History of the Weltbühne and its Circle, Berkeley: University of California, 1968, OCLC 334757, p. 286.

- ^ Ross, p. 147.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 304.

- ^ Jay Michael Layne, "Uncanny Collapse: Sexual Violence and Unsettled Rhetoric in German-language Lustmord representations, 1900–1933", Dissertation, University of Michigan, 2008, OCLC 719369972, p. 14, note.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, pp. 364–66.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 393.

- ^ Ross, p. 362.

- ^ Thomas Kubetzky, "The Mask of Command": Bernard L. Montgomery, George S. Patton und Erwin Rommel in der Kriegsberichterstattung des Zweiten Weltkriegs, 1941–1944/45, Dissertation, Technical University of Brunswick, 2007, Geschichte 92, Berlin/Münster: LIT, 2010, ISBN 9783643103499, p. 81 (in German); also "Deutsche und britische Kriegsberichterstattung", in: Massenmedien im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, ed. Ute Daniel and Axel Schildt, Industrielle Welt 77, Cologne: Böhlau, 2009, ISBN 9783412204433, p. 363 (in German)

- ^ Deák, p. 40.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 112.

- ^ Andreas Hempfling, Organisationsstruktur und Regulierungspolitik der Zeitschriftenwerbung im Dritten Reich, Munich: GRIN 2005, ISBN 9783638673303, note 19 (print on demand) (in German)

- ^ Irene Guenther, Nazi 'Chic'?: Fashioning Women in the Third Reich, Oxford/New York: Berg, 2004, ISBN 9781859734001, p. 441.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, pp. 414–15.

- ^ de Mendelssohn, p. 417.

- ^ Hempfling, n.p.

- ^ "Berliner Illustrirte: Die Fahne hoch", Der Spiegel issue 7, 1961 (in German).

Further reading

[edit]- Christian Ferber. Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung. Zeitbild, Chronik, Moritat für Jedermann 1892–1945. Berlin: Ullstein, 1982. ISBN 9783550065866. (in German)

- Wilhelm Marckwardt. Die Illustrierten der Weimarer Zeit: publizistische Funktion, ökonomische Entwicklung und inhaltliche Tendenzen (unter Einschluss einer Bibliographie dieses Pressetypus 1918–1932). Minerva-Fachserie Geisteswissenschaften. Munich: Minerva, 1982. ISBN 9783597101336 (in German)

External links

[edit]- Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung 1925, 1935, 1936, digitised at Fulda University of Applied Sciences

- Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung 1941, digitised at Fulda University of Applied Sciences

- Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung 1915,1917, digitised at Bibliothèque nationale de France

- 1891 establishments in Germany

- 1945 disestablishments in Germany

- Defunct magazines published in Germany

- German-language magazines

- Magazines established in 1891

- Magazines disestablished in 1945

- Magazines published in Berlin

- Photojournalistic magazines

- News magazines published in Germany

- Weekly magazines published in Germany