Broad Street Station (Philadelphia)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2012) |

Broad Street Station at Broad & Market Streets was the primary passenger terminal for the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from 1881 to the 1950s. Located directly west of City Hall – 15th Street went under the station – the northwest section of Dilworth Plaza and the office towers of Penn Center now occupy the site.

History

The original station was designed by Wilson Brothers & Company, and completed in 1881. It was one of the first steel-framed buildings in the United States to use masonry not as structure, but as a curtain wall (as skyscrapers do).[1] Initially, trains arrived via elevated tracks built above Filbert Street. By 1885 the land between the station and the Schuylkill River had been purchased and cleared, and a 9-block viaduct constructed.

Broad Street Station was dramatically expanded by renowned Philadelphia architect Frank Furness, 1892-93. Wilson Brothers designed a new train shed (1892), that was constructed high over the existing sheds, which were subsequently demolished. The new shed had the largest single span of any station roof in the world - 306 ft (91 m). In 1894 the PRR moved its headquarters from Fourth Street to the office building above the station. In the 1930s PRR headquarters moved to the newly-built Suburban Station Building at 1600 Filbert Street (now John F. Kennedy Boulevard). The train shed suffered a massive 1923 fire, and was demolished. The station itself was demolished in 1953, a year after train service to it had ceased.

Location and services

Broad Street Station dominated the center of the city. Trains would leave the station two stories above street level on a viaduct known as the "Chinese Wall" and run west to cross the Schuylkill River on tracks that bisected the western half of Center City Philadelphia. Fifteenth Street ran beneath the station's lobby, and the numbered streets up to 24th ran beneath the viaduct. John F. Kennedy Boulevard traces a similar path today.

The station was renowned for its architecture but cursed for inundating the heart of the city with the smoke and noise of the day's steam locomotives. The Chinese Wall also made Center City north of the station unfashionable, as the area was cut off from the rest of downtown. Passengers arriving at Broad Street Station could make connections to the rest of the city on the numerous trolley lines on Market Street and 15th Street, or on Philadelphia's east-west Market-Frankford Subway-Elevated Line (beginning in 1907) or the north-south Broad Street Subway starting in 1928. The latter two were heavy rail lines that crossed under City Hall.

Leaving Broad Street Station, passengers would first arrive at West Philadelphia Station at 32nd and Market Streets on the west side of the Schuylkill, which in 1933 was replaced by 30th Street Station. The lines then split in three directions:

- Trains heading west toward Harrisburg would take the PRR line to 40th Street Station, 52nd Street Station, and Overbrook Station. Trains heading northwest along the Schuylkill would split from this line after 52nd Street toward the stations at Wynnefield Avenue and Cynwyd.

- Trains heading north toward New York City or east across the Delaware River to New Jersey would run through North Philadelphia, North Penn Junction, and Frankford Junction stations, before splitting off.

- Trains heading south would take the Baltimore & Washington RR Central Division line through Angora.

Today all these railroad lines, except for the one between 30th Street and Broad Street stations, remain intact, run by SEPTA or NJ Transit.

Architecture

The architecture of Broad Street Station was typical of Furness's buildings in central Philadelphia in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Furness's structure looked much like a web of Gothic spires and arched windows, with considerable modification from their medieval sources. His work expanded on a similar structure originally constructed by the Wilson Brothers & Company a mere decade before. Furness's windows were often rounded and did not use pointed chancels.

The lower levels of the structure were heavy and rusticated, recalling the work of H. H. Richardson from the previous decade, while the spandrels of the upper stories emphasized the building's verticality. The frame for the stone structure was largely made of iron and steel, and on the interior the structural techniques were often displayed by balustrades and columns that in places revealed the rivets that held them together. The formal style of the building was altogether not unlike that of Furness's building for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, which he completed in 1876, or his University of Pennsylvania Library, designed in 1888.

As the station expanded after 1881, additional train sheds were added to cover additional tracks, twelve in all by 1891. They were eventually replaced by a single shed, which, upon its completion in 1892, had the largest single span of any station roof in the world (91 m - 298 feet), and ultimately covered 16 tracks.

PRR later hired Furness, Evans & Company to design the Arcade Building, an office building of the same red brick, stone and terra cotta as the station, that connected to it through a pedestrian bridge over Market Street. This relieved much of the pedestrian traffic at street level, and the City permitted the Arcade Building to be built over the 15th Street sidewalk.

Even in its early years, there were flaws in the operation of Broad Street Station. The station could not accommodate passenger trains passing through the city without time-consuming back-up moves. The other major problem was that it took a number of engine moves to turn around commuter trains, which had become the station's main business because of its proximity to the downtown area.

The first problem would remain unsolved despite a proposal for a tunnel in North Philadelphia that was to run to the Broad Street Station area and then emerge above ground to meet the lines coming out of the station.[citation needed] The other problem began to be alleviated with electrification of the rail lines, starting with the Paoli service to the railroad's "Main Line", starting on September 11, 1915.[2] In 1918 service to Chestnut Hill (today's Chestnut Hill West) was opened, and the two busiest commuter services were dealt with.[citation needed]

In 1928 two more lines, West Chester/Media and Chester/Wilmington, would go under wire, and in 1930 Norristown and Trenton would be electrified, the latter being the first segment of electrification of today's Northeast Corridor, which was completed to Penn Station, New York, in 1933.

The train shed was destroyed by a fire on June 11, 1923. The fire began about 1:00 a.m. and burned for two days. Amazingly, work on clearing the debris began even while the fire was still smoldering. The steel skeleton that remained was removed; thereafter, the train platforms operated while covered by small, "umbrella" shelters. These replacements were destroyed by another fire that began at 9:38 a.m. on September 12, 1943 and were replaced by a similar structure that remained for the last ten years of the station's existence.

Demise

In the 1920s and '30s the Pennsylvania Railroad built two new stations: 30th Street Station, which is now the main intercity hub for Philadelphia rail travel, and Suburban Station, a stub line from 30th Street Station to a tunnel ending northwest of City Hall, just north of Broad Street Station. (Around 1984 this line was extended east as part of the Center City Commuter Connection tunnel.) 30th Street Station was a through railway station that did not require intercity trains to turn around to exit the station (but a loop track was proposed just south of the station to allow the through east-west trains to come close to the center of the business district), while Suburban Station took over the electric commuter trains. In July 1947 Broad St scheduled 55 weekday departures: 9 to the south, 8 that would head west from Zoo, and 38 that would turn east from Zoo (14 of which would cross the Delair bridge).

Broad Street ultimately suffered the fate of many of Furness's institutional buildings, as it was closed in 1952 and razed in 1953. The last departure of a scheduled train was train 431 to Washington at 0110 on 27 April 1952; the last train was the farewell special that evening. The land once occupied by the station and its access tracks is now the commercial heart of the city, known as Penn Center, including buildings such as the 54-story Mellon Bank Center. Today all that remains of the building is a historic marker on 15th Street commemorating the site.

A bas-relief mural by Karl Bitter, The Spirit of Transportation,[3] located in the northwest corner of the main waiting area at 30th Street Station, was originally located in Broad Street Station.

-

Seals of the State of Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the City of Philadelphia, from the PRR boardroom at the Broad Street Station. Now at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania.

-

The Spirit of Transportation (1895) by Karl Bitter. Now installed at 30th Street Station.

-

City Hall and the Bridge over Market Street (1912), lithograph by Joseph Pennell.

-

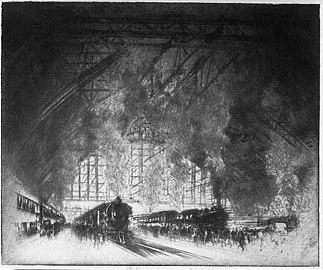

The Trains That Come, the Trains That Go (1919), etching by Joseph Pennell.

-

The approach into Broad Street Station

See also

References

- ^ James F. O'Gorman, et al., Drawing Toward Building: Philadelphia Architectural Graphics, 1732–1986, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986), pp. 140–42.

- ^ Tatnall, Frank (Fall 2015). "A Century of Catenary". Classic Trains. 16 (3): 26.

- ^ Spirit of Transportation

- Railway stations in Philadelphia

- Transportation in Philadelphia

- History of Philadelphia

- Stations along Pennsylvania Railroad lines

- Stations along Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad lines

- Frank Furness buildings

- Demolished railway stations in the United States

- Demolished buildings and structures in Pennsylvania

- Penn Center, Philadelphia

- Former Pennsylvania Railroad stations

- Sculptures by Karl Bitter