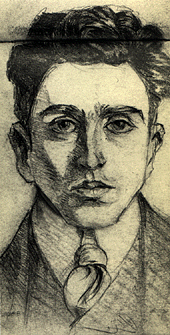

Carlo Michelstaedter

Carlo Michelstaedter or Michelstädter (3 June 1887 – 17 October 1910) was an Italian writer, philosopher, and man of letters.

Life

Carlo Michelstaedter was born in Gorizia, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian County of Gorizia and Gradisca, as the youngest of four children of Albert and Emma Michelstaedter Coen Luzzatto. His older siblings were Gino (1877–1909), Elda (1879–1944), Paula (1885–1972). His full name was Carlo Raimondo (Gedaliah Ram). His father was the director of the local branch of the Trieste-based Assicurazioni Generali insurance company. The Michelstaedters were an Italian-speaking upper middle class Jewish family of Ashkenazi origin.

His sister Paula remembered him as a child fearful of the dark and heights, stubborn and not at all prepared to apologize for any misbehavior. In school, he was judged "not very suitable (minder entsprechend)" for having intentionally and frequently disturbed the lessons during the year.

His father was the chairman of the Gabinetto di Lettura Goriziano, a local cultural association for the fostering of literary culture, and he pushed his son towards literary study. His mother Emma Luzzatto came from an old and renowned Jewish family of Italian irredentist leanings. Carlo was considered an introverted boy, but by the end of high school (completed in Gorizia), he developed into a brilliant, athletic, intelligent youth. He enrolled in the department of mathematics at the University of Vienna, but soon moved to Florence, a city he savored for its arts and language. There he formed friendships with other students, and in the end enrolled in the department of letters of the local Istituto di Studi Superiori (1905). He majored in Greek and Latin, and selected for his laurea thesis a philosophical study of persuasion and rhetoric in ancient philosophy. In 1909 he returned to Gorizia and set himself to work on the thesis.

By about the fall of 1910, he completed his work, finishing the appendices by 17 October. He was surely very tired, and that day he had a fight with his mother, who complained he had not wished her a happy birthday. Left alone, Carlo took a loaded pistol he had in the house and killed himself. One of his friends from Florence, a Russian woman, had also committed suicide, and probably also a brother who lived in America. Friends and relatives published his works and collected his writings, now in the Biblioteca Civica di Gorizia.

He is buried in the Jewish cemetery in Rožna Dolina near Nova Gorica, Slovenia.

Thought

Tracing the development of Michelstaedter's ideas is difficult: His philosophical vision seems to have formed suddenly, and his brief life didn't allow for time to explore other directions. For him common life is an absence of life, narrow and deluded as it is by the god of pleasure, which deceives man, promising pleasures and results that are not real, although he thinks they are. Rhetoric,—that is the conventions of the individual, the weak, and society—comprise social life, in which man overpowers nature and himself for his own pleasure. Only by living in the present as if every moment were the last can man free himself from the fear of death, and thus achieve Persuasion; that is, self-possession. Resignation and adapting oneself to the world, for Michelstaedter, is the true death.

Works

- Il dialogo della salute (1909), edited by Sergio Campailla. Milano: Adelphi Edizioni, 1988.

- Poesie (1905–1910), edited by Sergio Campailla. Milano: Adelphi Edizioni, 1987

- La persuasione e la rettorica, translated as Persuasion and Rhetoric with an introduction and commentary by Russell Scott Valentino, Cinzia Sartini Blum, and David J. Depew (Yale University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-300-10434-0)

- La persuasione e la rettorica – Appendici critiche, edited by Sergio Campailla. Milano: Adelphi Edizioni, 1995.

- Epistolario, edited by Sergio Campailla. Milano: Adelphi Edizioni, 1983.

- Diario e scritti vari

- Opere, edited by G. Chiavacci, Sansoni, Firenze 1958

- Scritti scolastici, edited by Sergio Campailla, Gorizia 1976

- Parmenide ed Eraclito. Empedocle : Appunti di filosofia, edited by Alfonso Cariolato and Enrico Fongaro. Milano: SE, 2003.

- Another English translation of La Persuasione e La Rettorica exists, by Wilhelm Snyman and Giuseppe Stellardi, with an introduction by Giuseppe Stellardi, published by University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, South Africa, January 2007. Preface by Wilhelm Snyman. ISBN 978-1-86914-091-5.

- La melodia del giovane divino, edited by Sergio Campailla. Milano: Adelphi Edizioni, 2010.

References

- Carlo Michelstaedter and the Failure of Language by Daniela Bini (University Press of Florida, ISBN 0-8130-1111-6 [1])

External links

- "Carlo Michelstaedter and the Metaphysics of Will" by Thomas J. Harrison MLN (106 (1991): 1012–1029)

- "The Michelstaedter Enigma" by Thomas J. Harrison in Review of Italian Thought 8–9 (Spring/Autumn, 1999, pp. 125–141)

- Michelstaedter devoted website (in Italian)